Killer 7: Guesses and Interpretations

Between the first two missions, there’s a longish expository cutscene that introduces us to the global context in which the mission you just completed takes place. It’s strikingly different in style to the rest of the game. It’s a lot rounder and safer-looking, with a sunny watercolor palette, wide camera angles, and figures drawn in a conventional realistic-cartoony anime style, with a vague patina of age, as if we’re watching Saturday morning television from a few decades ago. (For all I know, they may have actually pieced this scene together from clips of old cartoons rather than making it from scratch. Either way, the sense that we’re watching television is presumably deliberate, given all the television imagery in the rest of the game.) The game proper looks more like Mignola than Miyazaki: stark, angular, shapes defined by shadows rather than outlines. When an out-and-out big-eyed anime girl shows up at the end of the first mission, it’s a shocking contrast. When an entire cutscene has a similar contrast in style, I find myself asking what happened. My first guess is that it’s a matter of perspective. We’ve been seeing the world through the disturbed and unreliable eyes of the Killer 7, and this is our first glimpse at how things seem to everyone else.

What we’re told is basically just a reiteration of stuff in the manual, but it seems more meaningful now, with the visuals to back it up. We’re told about how the world united into a new order in 1998, built improbable ocean-spanning highways, and banned missiles. We’re told how a terrorist group, referred to in the cutscene only as “the smiling faces”, disrupted a high-profile UN ceremony, and how assassins working in secret were the only possible weapon against this new threat. We’re shown a couple more salient details: a more conventional assassination by someone who might be Harman Smith, a view of the UN ceremony cut short by a suicide bombing.

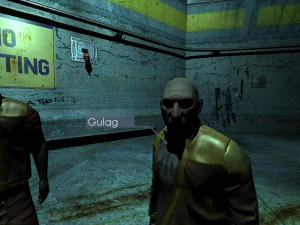

So, there’s our connection to the monsters in the game: they’re suicide bombers too. They fight you by charging at you and exploding. But they’re also a far cry from the politically-motivated terrorists fighting against the implied hegemony in the cutscene. They’re distorted and demonic of visage, with bumpy, reptilian-looking skin (from the biologically-generated explosives underneath, we’re told), capable of surviving the loss of an arm or a head without much difficulty, and motivated solely by madness: they were all innocent bystanders until they were transformed by the divine power of Kun Lan’s “god hand”. How did we get here from there?

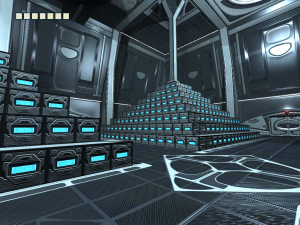

There is every possibility, at this point, that these creatures are purely symbolic, a madman’s nightmare of his enemies. Which is not to say that they’re necessarily just hallucinations. It’s still early in the game, and a lot remains unaddressed, but a lot of what goes on in the missions seems kind of shamanic, a matter of passing ordeals in the spirit-world in order to have effects in the mundane world. Particularly the business in mission 1 of the threshold guardian, keeper of the “Vinculum Gate” which leads “to another world”. (He’s imagined as something like the bouncer at a club, which strikes me as another dreamlike touch, conflating two similar roles.) Once you satisfy him, you go through the gate, through an area with loud dance music playing, fight a boss, and then loop around and go back into a place that looks pretty much like where you’ve already been, except that this time you’re allowed to use the elevator to the end-of-mission encounter. Taking a trip through the astral plane to reach reality, perhaps? It’s kind of like how some of the normal-world-to-dark-world transitions in the original Silent Hill worked, except that here, the dark world is the one you start in.

Comments(0)

Comments(0)