The Dark Crystal

I have a perverse fondness for games adapted from movies. There’s a kind of art to them that isn’t found in original works, a balancing act on the designer’s part that I find fascinating, like a highly constrained poetic form. Much of the enjoyment comes, not from the gameplay itself, but from seeing how they used the techinques of the new medium to try to reproduce the feel of the original.

I have a perverse fondness for games adapted from movies. There’s a kind of art to them that isn’t found in original works, a balancing act on the designer’s part that I find fascinating, like a highly constrained poetic form. Much of the enjoyment comes, not from the gameplay itself, but from seeing how they used the techinques of the new medium to try to reproduce the feel of the original.

Of course, the answer is often “badly”. Sturgeon’s Law applies, and games based on movies don’t have to try as hard to get an audience. And so it has become common wisdom that games based on movies are hackwork, and best avoided, with the possible exception of those based on the Star Wars franchise (which are more often original works set in the Star Wars universe than adaptations per se). But I don’t care. As far as I’m concerned, movie adaptations cannot be judged by the same criteria as other games.

And in the case of The Dark Crystal, it’s also separated from the bulk of games by history. This seems to be one of the earliest games based on an official movie license — it was released in 1982, the year that also gave us the Tron coin-op game and the infamous Atari 2600 E.T. It was certianly the first movie to be officially adapted as a graphic adventure. So, unlike today’s adaptations, it didn’t have a lot of established techniques to work with. Roberta Williams had to figure the whole thing out from scratch: how close to adhere to the source material, how much to add.

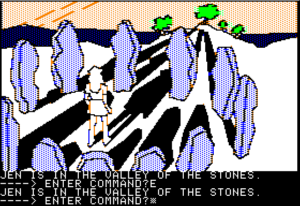

Probably the strangest choice she made was to include Jen, the player character, in the illustrations. Understand that there is no animation, and that Jen’s picture is not a player-controlled avatar. He’s just part of the illustration for each room. This probably makes it the first adventure game with third-person graphics. Appropriately, the text is also in the third person: instead of the Infocom-standard “You are in the Valley of the Stones” or the Scott-Adams-style “I am in the Valley of the Stones”, it’s “Jen is in the Valley of the Stones”. This is very unusual for an adventure game, but I can understand why it was done this way: the illustrations are mostly based on still images from the movie showing Jen, and once you have that, you’re clearly not seeing it through the player character’s eyes. Also, unlike previous Sierra games, Jen is a character distinct from the player, rather than a projection of the player into the gameworld. This would become the norm for them, even as they dropped the third person grammar and addressed the player as the player character (“Oh no, Sir Graham! You’ve fallen off a cliff!”)

I wonder how much these experiments with presentation inspired the development of King’s Quest? The on-screen player character seems like it could be a stepping-stone towards the fully-animated player-controlled avatar. Perhaps this game’s importance to the history of the medium has been grossly underestimated, due to its being regarded as merely a movie adaptation.

In other respects, the environment has a lot in common with both King’s Quest and Time Zone: it’s mostly a grid of exterior scenes, sparsely scattered with usable objects. This is actually pretty appropriate to the source material, as The Dark Crystal is in large part a travelogue of a bizarre fantasy world, with lots of shots devoted to showing off the sets. I only wish the game had more interactive details. The setting is more fully implemented than in Time Zone, at least to the extent that you can often get one-sentence descriptions of scenery objects, but it doesn’t do justice to the film’s twitching, chittering wildlife. There’s a bit in the film involving what I can only describe as mountain sea-anemones. They lie still, looking like tentacled plants, until, at Jen’s approach, they all simultaneously and busily withdraw into their crevices in the rock. I’d love to be able to trigger that kind of reaction in a game.

Comments(1)

Comments(1)

[…] Carl Muckenhaupt mentions in his (highly recommended) posts about the game, it’s tempting to see the graphics as a transitional step between the first-person […]