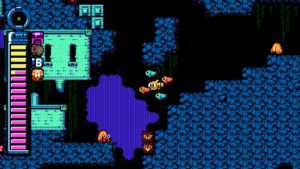

Before I go any farther, I want to at least briefly address the most significant gaming experience I had during the recent hiatus, before the details completely slip my mind. Animal Well was the darling of the indie puzzle game scene when it came out, largely thanks to its multi-layered puzzle stucture, visual inventiveness, tons of secrets at all levels of accessibility, and general enigmatic vibes.

In form, it’s a 2D metroidvania — you platform around a large connected environment, collecting tools that let you access more of the place. What exactly is that place? It’s a mystery. It’s clearly a constructed environment, largely made of damp masonry and clanking machinery, but what is its purpose? And why is there an ostrich down there? I say “down there” because obviously the title suggests that you’re underground, but even that much isn’t clear. There’s a large vertical shaft in the middle of the map, stretching up from room to room, and for a long time, I operated under the speculation that if I could just get to the top of that shaft, I could emerge into the world outside. This turns out not to be the case: the map has both horizontal and vertical wraparound. It’s a self-contained space, brooking no escape by normal physical means. And it’s haunted. Some of the exotic animals you encounter are definitely ghosts. Possibly all of them are. Are you a ghost? It’s not at all clear what you are. A little round thing. A lot of people seem to call the player character a “blob”, but that doesn’t sit right with me. You clearly have feet. Blobs don’t have feet.

As a metroidvania, it does require a certain amount of platforming skill, and I wouldn’t recommend it to players who aren’t accustomed to that. But part of the brilliance of the game is the extent to which skills and tools can substitute for each other. For example, there’s a frisbee you can find that, with just a little effort, you can throw and then jump on it — something that you’ll probably discover by accident — and just glide over some of the more difficult platforming sections. There’s a bubble wand — yes, nearly all of the tools are toys — that makes bubbles that you can jump on to gain a little elevation. It only creates one bubble at a time, but eventually you find a wand without this restriction, and can use it to climb a chain of bubbles to any height. More skilled players than me manage to do the same with the original bubble wand, somehow jumping from one bubble and creating a new bubble to jump onto at the same time, accessing secrets that I only found much later.

These tools (or toys) all have the virtue of general applicability, that they behave the same way in all places and have emergent uses. And to be fair, not every tool in the game is like that. A UV lamp that reveals invisible messages is only useful for that specific purpose. But in general, the degree of general applicability here is at a level above most other games of the sort. I think of Prince of Persia (2008) as epitomizing the opposite approach: there, you get special mobility powers, but you can only activate them on special colored plates, removing the possibility that the player will use them to break sequence, but also removing any sense of experiment and discovery from their use.

But Animal Well isn’t so concerned with stopping you from breaking sequence. And that would be a good segue into describing my personal experience of the ending, but I still have to set it up a little, by describing the game’s layers.

The game’s puzzle content has four known layers. (There may be more that haven’t been discovered yet.) The first and most obvious layer is just playing the game, collecting four flames that let you into an endgame area that gets you to an ending, where the credits scroll by over a fireworks display. This is reasonably solvable, and you could stop playing there, but it’s clear that this ending isn’t really the end — after the credits, you’re simply in the same place, with a key that lets you into a few previously-inaccessible rooms, notably including a sort of home for your character, but still doesn’t actually get you out of the well.

The second layer involves finding 64 “Secret Eggs” to reach a second ending, where you finally escape to a second area exterior to the well. This is still reasonably completable by a solo player who’s avoiding spoilers, if they’re still enjoying the game and don’t feel like they’re done with it yet. I personally was such a player: I found all the eggs by myself, but then got stuck and had to seek hints on how to proceed from there, for reasons I will describe.

In addition to the 64 Secret Eggs, there are a number of Secret Bunnies, which, when found, go to the post-second-ending exterior area, letting you know that this is the goal of layer 3. Layer 3 is absolutely meant to be a community project. A solo player will be able to find a few bunnies, but there’s one that requires at least fifty different players to share information, and others that are simply so obscure that they might as well require fifty players.

Notably, the first three layers intermingle. By the time you reach the first ending, you’ve definitely found some eggs. If you’ve explored thoroughly enough to find all the eggs, you’ve inevitably picked up a few of the easier bunnies as well. The fourth layer isn’t like that. It involves performing difficult and/or unmotivated actions like eating 100 healing fruits while your health is already full or speedrunning to the second ending in under 60 minutes. The developers have said that they didn’t expect this layer to ever be fully completed, but the player community managed it anyway.

So, now I can tell my spoiler-laden tale about what happened to me in the endgame. Just before the first ending, there’s a bit where you have to open a door by pressing four buttons at the ends of mazy passageways in a four-room block, while pursued by a floating black scary ghost-cat-thing. I’ve since learned that it’s officially called the Manticore, but this name does not appear in the game; there’s very little text in the game, the better to let the player figure stuff out on their own. The Manticore periodically attacks you with hard-to-avoid eye-beams that reflect off walls, and the button state resets if you die, so this is a very high-pressure situation — especially if, like me, you’re not very good at the platformy bits and prefer to bypass obstacles with cleverness. And so that’s what I did here. By means of a magic flute, I could teleport to the safety of a hub room every time I successfully pressed one of the buttons, and from there, find some fruit to heal up and a save point to lock in that button press before attempting another. In this way, I pressed all four buttons. Once the door is open, you can go through it without going through the area that triggers the Manticore to start chasing you, so getting to the fireworks and the first ending was a snap.

So, now I can tell my spoiler-laden tale about what happened to me in the endgame. Just before the first ending, there’s a bit where you have to open a door by pressing four buttons at the ends of mazy passageways in a four-room block, while pursued by a floating black scary ghost-cat-thing. I’ve since learned that it’s officially called the Manticore, but this name does not appear in the game; there’s very little text in the game, the better to let the player figure stuff out on their own. The Manticore periodically attacks you with hard-to-avoid eye-beams that reflect off walls, and the button state resets if you die, so this is a very high-pressure situation — especially if, like me, you’re not very good at the platformy bits and prefer to bypass obstacles with cleverness. And so that’s what I did here. By means of a magic flute, I could teleport to the safety of a hub room every time I successfully pressed one of the buttons, and from there, find some fruit to heal up and a save point to lock in that button press before attempting another. In this way, I pressed all four buttons. Once the door is open, you can go through it without going through the area that triggers the Manticore to start chasing you, so getting to the fireworks and the first ending was a snap.

I proceeded to find all the eggs, even the one that nearly everyone misses, which is another story of my own cleverness, but I’ll spare you for now. Along the way, I found a hidden room to the left of the Manticore area, glimpsing it from a roundabout passageway that didn’t provide access to its contents. Figuring out how to get into that room while the Manticore chased me was a little tricky, but manageable. It turned out that the throne-like thing in the center was called an Incubator — clearly linked to all the eggs! — and there was another room to the left of the Incubator room, containing what looked like a door with the Manticore’s face on it. So at this point, my theory about how things were going to proceed was this: I would find all the eggs, and I would put them in the Incubator, and then something would happen, possibly the hatching of a new being capable of fighting the Manticore with me. Whatever happened, in the end the Manticore would be dead and the door would open.

This proved inaccurate in several ways. First, you don’t put all 64 eggs into the Incubator; getting them all gives you access to a special 65th egg, with the Manticore’s face on it, just like the door, and this is the thing you put in the Incubator. Second, putting the 65th egg in the Incubator didn’t do anything. “Maybe it takes a while to hatch”, I thought. And I tried waiting for it to hatch, but the Manticore kept killing me. And this is the point where I sought hints.

What I learned from the hints is that I had unintentionally broken sequence. The way it’s supposed to go is: After you press the four buttons and open the door (in a single sally, because you are skilled and brave), the Manticore chases you all the way to the first ending and is killed by the fireworks. Freed from the pressure of dodging its eyebeams, you find your way into the Incubator room, but can’t go any farther to the left, because the only thing that can break the blocks in the way (which didn’t even register as an obstacle to me) is the Manticore. And so you embark on a quest to find all the Secret Eggs to obtain the 65th egg, because it is a Manticore egg, and will hatch into a second Manticore. The “door” with the Manticore’s face on it is not related to this, and has a solution that’s fairly easy to find when you’re freely inspecting the place without getting killed all the time.

So, my first reaction is dismay — dismay that, through my cleverness, I had tricked myself out of what seemed like it would have been a more satisfying first ending, one where you actually defeat the final boss instead of just avoiding it. Then came the realization that I had hunted all those eggs for no actual purpose: all you need to get the second ending is a Manticore, and I still had my first one. The second ending also gets rid of the Manticore, but in my playthrough, I already had a Manticore egg in the Incubator when this happened, and when I returned there, it hatched. So I was only Manticore-free very briefly, and have no way to dispense with the one that remains.

At least the game takes into account the possibility of this happening, and doesn’t break completely. I know I’m not the only one to have had this experience, and I imagine speedrunners must do what I did on purpose.

Comments(0)

Comments(0)