Wizardry I: The Control Center

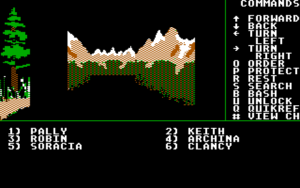

The player’s mission in Wizardry I is to slay the wizard Werdna and obtain the amulet he stole from the mad overlord Trebor1The names Werdna and Trebor are the reversed first names of Andrew Greenberg and Robert Woodhead, the game’s authors. Greenberg and Woodhead’s initials also form the basis of the layout of dungeon levels 8 and 9., but the game only announces this after a major battle on dungeon level 4 (out of 10). Before that point, you’re just dungeon-delving for its own sake. It’s a little like how Final Fantasy 1 only starts its main plot after the first dungeon, and in both cases it’s probably based on how tabletop D&D tends to go: only after the first few sessions does anyone think of turning it into a campaign.

But here in Wizardry, the mission start comes unusually far into the thing. In fact, in a sense, it’s right at the end. Here’s the thing: Dungeon levels 5 through 8 are useless for the actual mission, except to the extent that you can use them to grind levels and loot. There are no stairs down from level 8. The only way to reach the last two levels and Werdna (other than by teleportation magic) is via the elevator on level 4, which you can only access if you have the blue ribbon you’re awarded at the same time you’re told of the mission. So there’s no obstacle to going straight down from the mission assignment to the endgame, if you’re arrogant enough to think you’re up to it.

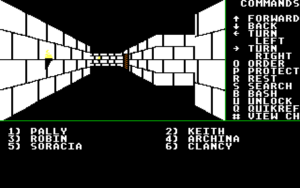

I’ve always found the whole situation a little confusing. The upper parts of the dungeon, at least, are the titular “proving ground” that Trebor uses to find heroes worth sending after Werdna. But to prove yourself worthy, you have to ignore a number of signs telling you that certain areas are off-limits and break into a section marked “Testing Grounds control center” and “Authorized personnel only”, where alarms go off, summoning monsters. A mention of “the remains of crystal balls and other magical artifacts all now broken” makes the place seem abandoned and overrun, but it’s still functional enough to dispense elevator keys on Trebor’s behalf. Just what’s going on here? We’re told that that Werdna is hiding in the depths of the maze, but the maze is apparently right underneath Trebor’s castle and features an elevator leading straight to Werdna’s lair. We’re probably supposed to chalk a lot of this up to the mad overlord’s madness.

One other thing about the battle of the control center: It yields significant loot, including a Ring of Death, a cursed item that drains the hit points of its wearer at an alarming rate. That might not sound good, but you have to bear in mind that it also costs a fortune to uncurse it — so much that you should probably give up on the character who put it on and roll up a new one. OK, that also doesn’t sound good. The good part is that the cost to remove a cursed object is proportional to what you can sell it for if you identify it without triggering the curse. There’s a certain risk in identifying cursed objects — the character doing the identifying can accidentally become cursed while identifying it — but successfully identifying and selling a Ring of Death is basically the point in the game where you stop worrying about money and start lamenting that there’s so little to spend it on.

| ↑1 | The names Werdna and Trebor are the reversed first names of Andrew Greenberg and Robert Woodhead, the game’s authors. Greenberg and Woodhead’s initials also form the basis of the layout of dungeon levels 8 and 9. |

|---|

Comments(0)

Comments(0)