Wizardry III: Combat

I’ve survived another trip to dungeon level 4. It was a close thing, though: fully half my party was dead by the time I made it out. (Fortunately, they all survived resurrection.) This time, though, it wasn’t due to any individual encounter. It’s because I spent too long wandering the dungeon and getting into fights. Not deliberately, either: I hit a teleporter I didn’t know about, and had to find a way back to the exit through uncharted ground. The upside is that it’s not uncharted any more.

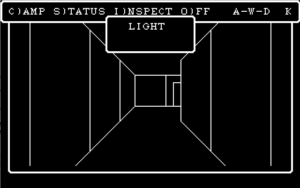

Since the primary distinguishing feature of my last session was more fights than I wanted, let’s talk a bit about what fights are like. The Wizardry combat system is the basis of turn-based combat in so many RPGs, notably including Final Fantasy. It’s all turn-based, or, more precisely, it’s what’s been called a “phased” system: you give every character their instructions for the round — whether to attack or cast a spell or whatever — and then there’s a certain amount of randomness in the ordering of the results, weighted by experience level and Agility. This includes the actions of the monsters.

Monsters come in homogeneous stacks, with up to four stacks per encounter, but act individually. The stacks (or “groups”, as the docs call them) are significant to the mechanics: when you specify a target for a spell or an attack, you specify the group, not the individual. Many of the combat spells affect an entire group at a time, which makes a sufficiently-advanced mage vastly more powerful than an equally-advanced fighter, who can kill at most one creature per round. Past a certain point, the fighter has only two purposes in the party: meat-shield, and conserving the mage’s spells by killing the less-threatening monsters the slow way.

Not that this makes them less crucial as parts of the party! Mages really, really need their meat-shields, because it’s the only kind of shield they can use. Although the interface doesn’t indicate this clearly, the party is divided into two rows. Only the first three slots are in melee range of the monsters. I don’t mean that there’s a reduced chance of hitting the back row, I mean the back row can’t be targeted by physical attacks at all. This is why samurai and lords are so valuable: they’re spellcasters that you can put in the front row without getting them killed. They are, in effect, their own meat-shields. Priests are almost as good in this role, in that they can wear armor that’s almost as good as a fighter’s, and in addition can carry enough healing power to compensate for the difference. But I’m still somehow not comfortable putting more than one priest in front.

Mind you, even in the back row, you’re vulnerable to spells. This is something I remember coming as a bit of a shock when I first encountered spellcasting monsters on dungeon level 2 of Wizardry I. I had gotten used to wiping out the monsters with group damage spells, and suddenly they were easily wiping me out using exactly the same techniques. It seemed somehow unfair, despite being symmetrical. Or, well, not entirely symmetrical: spellcasting monsters tend to come in groups, which increases their chance of getting in the first cast, which can determine the outcome of the entire battle. It’s a good thing that your initiative goes up with your experience level.

Frequently, combat begins with a surprise round, in which only one side gets to attack. The interesting thing about this is that you can’t cast spells in a surprise round, which completely changes the dynamic. The priestly ability to dispel undead isn’t considered a spell, so that’s pretty much your only option for disposing of monsters en masse. Until, that is, you realize that this is what scrolls are for. I had written them off as worthless at first, just an expensive way of getting the equivalent of an extra spell slot, but a Katino (sleep) scroll used in a surprise round against against a group of spellcasters has on more than one occasion prevented them from getting off a single spell.

Comments(0)

Comments(0)