IFComp 2007: The Lost dimension

Next we have a text-based RPG with an experimental GUI. Spoilers follow the break.

Read more »

Next we have a text-based RPG with an experimental GUI. Spoilers follow the break.

Read more »

Frankly, I find it hard to play Psychonauts without thinking of the Ratchet & Clank games. I suppose that they’re both basically just swimming in the general soup of 3D platformers, all of which imitate each other to some degree, but there are a few specific aspects that seem particularly Ratchettian. There’s the general approach to combat sequences: in most cases, battles can be won by either having skill and good reflexes, or by assessing the situation and choosing the one weapon in your arsenal that makes it easy. There’s the sliding-along-a-rail sequences, although the two games approach that in different ways: R&C made the “shredding” into something set apart in special areas that demanded tricky sequences of timed jumps, and while Psychonauts has a couple of bits that seem to be intended to evoke the same experience (but aren’t as difficult), it mainly just adds the rails to bits of the regular terrain, letting you slide down bannisters as an alternative to walking down the stairs and the like.

Frankly, I find it hard to play Psychonauts without thinking of the Ratchet & Clank games. I suppose that they’re both basically just swimming in the general soup of 3D platformers, all of which imitate each other to some degree, but there are a few specific aspects that seem particularly Ratchettian. There’s the general approach to combat sequences: in most cases, battles can be won by either having skill and good reflexes, or by assessing the situation and choosing the one weapon in your arsenal that makes it easy. There’s the sliding-along-a-rail sequences, although the two games approach that in different ways: R&C made the “shredding” into something set apart in special areas that demanded tricky sequences of timed jumps, and while Psychonauts has a couple of bits that seem to be intended to evoke the same experience (but aren’t as difficult), it mainly just adds the rails to bits of the regular terrain, letting you slide down bannisters as an alternative to walking down the stairs and the like.

And then there’s the pie menus. This is the main thing that keeps reminding me of R&C, because it’s something I use all the time. If you want to select a psychic power or an inventory item in Psychonauts, or a weapon or gadget in Ratchet & Clank, you can do it through an interface that shows eight choices in a circle, from which you select one by pointing the analog stick in the appropriate direction. This is one of R&C‘s most distinctive features, and the menu in Psychonauts resembles it more strongly than other pie menus I’ve seen (such as the one in The Sims), which tend to be based on using a mouse rather than a joystick, and have a variable number of slots rather than always eight (resulting in, for example, a triangular configuration if there are only three options). And the strange thing is that, even though this resemblance is strong, it’s very superficial.

See, the point of the pie menu in Ratchet & Clank is that it was your quick-selection option. That game had a lot more than eight weapons, and the pie menu wasn’t the primary way to select them. You always had the option of opening up the screen that had the full set displayed in a grid, pushing a cursor around to select the correct square, and resuming the game. But if you were using a particular item a lot, it was more convenient to put it into one of the eight quick-selection slots where you could just press a button, flick the joystick, and release. In the sequels, bringing up the circle menu didn’t even pause the action. Crucial to the way it worked was that you could assign which item went in which slot yourself. If you got used to flicking upward for your main weapon, and then decided to switch to using some other weapon as your main one, you could just replace it.

This conceptual niche, the user-assignable quick-selection option, exists in Psychonauts, but not through the circle menu. Rather, the game lets you assign three different psychic powers to different buttons — on a gamepad, keyboard, or mouse — while a fourth button activates the currently-selected inventory item. That’s your quick-selection: selecting which button to press. The pie menu, then, takes the role of that page with the complete grid in R&C. There are exactly eight psychic powers, so they all fit on the same circle, and you can’t alter their positions on it. There are sometimes more than eight inventory items, in which case the game lets you page between multiple batches of eight.

It really seems like this aspect of the user interface was decided on because it was cool, not because it was appropriate. It’s a menu in which you don’t use any particular option frequently (because the powers you use frequently are the ones you never remove from their button assignments), that isn’t user-alterable, and which, in the case of the inventory menu, sometimes changes itself spontaneously. All of which means it loses the chief advantage of the pie menu: its “gestural” nature, the ability to use it from muscle memory. It might as well be a traditional list.

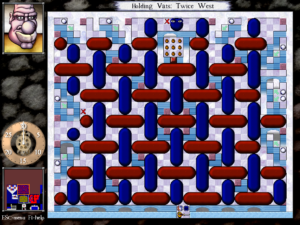

I’ve come to really like the improvements that have been made to the DROD user interface. Basically, each episode makes more information available.

I’ve come to really like the improvements that have been made to the DROD user interface. Basically, each episode makes more information available.

For example, one of the basic mechanisms in DROD is orbs that open, close, or toggle gates when struck. The City Beneath also has pressure plates that do the same when trod on (which means you can trigger them from a distance by inducing monsters to walk over them). But the orbs and pressure plates are not necessarily near the gates they affect. In the original DROD, if there were multiple orbs in a room, the only way to know what they did was to try them out, which you could only do for the ones that are acessible at any moment.

Well, ever since Journey to Rooted Hold, you can click on these controls to highlight the doors they affect, in colors indicating whether it opens, closes, or toggles each door. I didn’t use this feature much when I learned about it, but it’s become a very big deal. One of the basic DROD room patterns is making the player hit a series of checkpoints in a specific order by giving each an orb that unlocks the door to the next. With the new UI, I can know in advance the order I’ll have to hit them in, and plan accordingly. Even in rooms where all the orbs are accessible from the beginning, it’s nice to not have to try them all out (and possibly render the puzzle unsolvable in the process because you let the cockroaches out too early or something).

Once they implemented this click-to-highlight system, the designers started using it in various other ways, such as clicking on an Evil Eye to show its line of sight, or (new in The City Beneath) clicking on a bomb to highlight the area that will be affected by its blast. This was never secret information. All bombs in the game have the same blast radius. So displaying that radius on demand is just a convenience. You know something? Conveniences are nice.

I actually didn’t notice most of these features in Journey to Rooted Hold, which wasn’t as aggressive about pointing them out as the new episode, but there was one enhancement that was hard to not notice: it added a clock to the screen whenever there was a timed event pending. Mainly this meant timing the spawn cycle of Roach Queens and Tar Mothers, both of which cause new stuff to appear every 30 turns. Knowing exaclty how soon that’s going to happen is often crucial, and it was easy to lose track when playing the original DROD.

The general principle here is that providing easy access to crucial information helps the player, by making the process of solving the puzzles easier, but doesn’t actually make the puzzle itself easier. A subtle distinction, perhaps, but an important one, and one that’s illuminated by my recent experiences with Roberta Williams’ Time Zone. Williams chose to make things inconvenient for the player, making you reload saves and do things over again because you used the wrong weapon or brought the wrong selection of objects into the endgame. She chose this, I think, because she was trying to create a difficult game, and the understanding of the time did not differentiate between difficulty in solving a game and difficulty in playing it.

The designers of DROD have a better idea of what their gameplay is about. It’s not about keeping secrets from the player. It’s about applying known rules in complex and novel ways.

It’s interesting, then, that they still choose to retain the possibility of hiding information in some ways. Let me explain: I’ve just reached the point in The City Beneath where the Living Tar makes its appearance. Living Tar, and its variant Awakened Mud, form DROD‘s version of ooze monsters. In its simplest state, tarstuff (the word applies to both forms) lies in inert pools covering multiple tiles, not crossable and only partially vulnerable to attack: Tar is invlunerable on its convex corners, while Mud is invulnerable everywhere but its corners. Either must be cleared away one tile at a time.

It’s interesting, then, that they still choose to retain the possibility of hiding information in some ways. Let me explain: I’ve just reached the point in The City Beneath where the Living Tar makes its appearance. Living Tar, and its variant Awakened Mud, form DROD‘s version of ooze monsters. In its simplest state, tarstuff (the word applies to both forms) lies in inert pools covering multiple tiles, not crossable and only partially vulnerable to attack: Tar is invlunerable on its convex corners, while Mud is invulnerable everywhere but its corners. Either must be cleared away one tile at a time.

Now, until cleared, tarstuff conceals any terrain features in the tiles it occupies, including orbs, pressure plates, gates, and even walls. This is significant information-hiding. The original King Dugan’s Dungeon had some puzzles that relied on tarstuff’s concealing properties. For example, there was a maze completely covered in tar, which you had to cut carefully lest you wind up with an invulnerable tar corner blocking the path you needed to take. This isn’t really in the DROD style as I’ve described it above, but it’s typical for the first game in a series to have a few klunkers.

The City Beneath provides a way to see what’s under tarstuff, but it isn’t a user-interface feature like the other things I’ve been describing. Rather, there’s an in-game “token”, a special tile type that effectively gives Beethro X-ray vision when activated, rendering all tarstuff translucent.

The City Beneath provides a way to see what’s under tarstuff, but it isn’t a user-interface feature like the other things I’ve been describing. Rather, there’s an in-game “token”, a special tile type that effectively gives Beethro X-ray vision when activated, rendering all tarstuff translucent.

I can think of three possible reasons why tarstuff visibility isn’t handled through a simple click like the other new information features. First, it could be that there will at some later point be puzzles that rely on concealing information with tarstuff. I hope this isn’t the case, because it’s difficult to imagine the result being anything more than a guessing-game, and I think the DROD designers are past that now. Second, it could be that the designers wanted to preserve the ability to play levels created in the older engines without drastically altering the play experience. I don’t know that that’s a great priority for them, though: surely some of those old levels are drastically altered by the ability to click on an orb to see what it does. Third, it could just be the difficulty of creating a user interface to deal with it reasonably. If you click on tarstuff to see under it, and you click on orbs to see what they affect, how do you see what’s affected by an orb concealed by tarstuff?