Games Interactive 2: Cryptograms

Previously, I lamented the lack of cryptograms in Games Interactive. Well, in the sequel, my wish is granted! Cryptograms are an entire category — although, weirdly, the name of the category is “Crypto Funnies”. I guess this has something to do with the fact that it’s the name of the first five puzzles in the list. As with the logic puzzles, the category contains four distinct sub-types: Crypto Funnies (four-panel cartoons with ciphered word balloons, which gives you enough context for the deciphering to be really easy), Cryptolists (ciphered lists of things that fit some theme, without the cues you’d get from full sentences), Variety Cryptograms (collections of ciphered texts fitting some theme), and “Dszquphsbnt!”.

Previously, I lamented the lack of cryptograms in Games Interactive. Well, in the sequel, my wish is granted! Cryptograms are an entire category — although, weirdly, the name of the category is “Crypto Funnies”. I guess this has something to do with the fact that it’s the name of the first five puzzles in the list. As with the logic puzzles, the category contains four distinct sub-types: Crypto Funnies (four-panel cartoons with ciphered word balloons, which gives you enough context for the deciphering to be really easy), Cryptolists (ciphered lists of things that fit some theme, without the cues you’d get from full sentences), Variety Cryptograms (collections of ciphered texts fitting some theme), and “Dszquphsbnt!”.

This last one is the name of Games Magazine’s regular cryptogram section; it’s the word “Cryptograms” shifted forward one place in the alphabet. The individual cryptograms within a Dszquphsbnt! are unrelated, and, as in Battleships and Paint by Numbers, are only grouped together here because they were originally published that way. Dszquphsbnt! is where the really tough cryptograms are — the ones where they make sentences without articles or other short words and with weirdly skewed letter frequencies, where your only way to get started is by noticing a long word (or, worse, combination of words) with an unusual pattern that identifies it. They don’t start out that way, though. Each Dszquphsbnt! set starts out easy and works its way up. In fact, the first cryptogram in each Dszquphsbnt! is a “Cryptoon”, which is basically the same idea as Crypto Funnies but with one panel and a caption instead of four panels and balloons. Unfortunately, in Dszquphsbnt!, this game leaves out the pictures. The Cryptoons are quite solvable without them, but what you end up with is a punch line without its context, and sometimes it’s a really inscrutable punch line, like “That looks like it says, ‘Machine wash warm, tumble dry medium, made in France'”. I think some of the Variety Cryptograms may have been originally published with pictures too, but that’s just a guess.

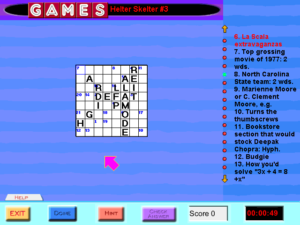

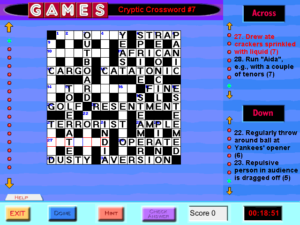

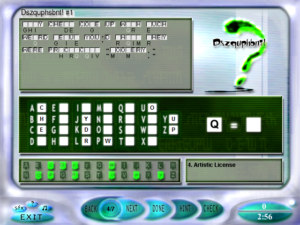

The basic cryptogram UI here, shared by all the puzzles in the category, isn’t the best I’ve ever seen, but it’s okay. It lets you select letters with either keyboard or mouse, and in the case of mouse, it lets you click on either a displayed alphabet or directly on the cryptogram. I mostly wound using it in a sort of hybrid style, clicking on the cryptogram to select a ciphertext letter and then typing the plaintext version via keyboard. Selecting any letter highlights all instances of it in the cryptogram, which is handy for eyeballing letter frequencies.

On the downside, it occasionally fails to respond to the keyboard, making me press a key multiple times to get it to register. Also, it lets you bind multiple ciphertext letters to the same plaintext, so sometimes I accidentally wound up with multiple distinct kinds of T on the screen. This is exacerbated by the way it removes the ciphertext letters from view when you bind them to plain text, so you have nothing visible to tell apart identically-bound letters. That is, it doesn’t take them away completely — there’s still a very faint ghost of the letter there, like they tried to gray it out but went too far. At least you can still click on it to highlight it, but what it really makes me want is a way to remove a letter’s binding, and the game doesn’t give us that. The ability to mess up the display without being able to unmess it interferes with the way I want to use the interface: not just as a way of entering answers that I’m sure of, but as a medium for exploring possibilities.

I said the cryptogram UI isn’t the best I’ve ever seen. You know what is? It’s the one where you have just one version of the text displayed, and selecting two letters swaps them in it — that is, selecting A and J, for example, replaces every A with a J and every J with an A. It’s simple, and it just naturally avoids the problems here. And if I’m not mistaken, this was the interface used by Cliff Johnson in games such as The Fool’s Errand and At the Carnival back in the 80s, so it’s not like it was unknown.

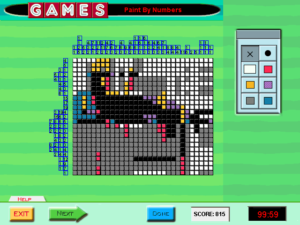

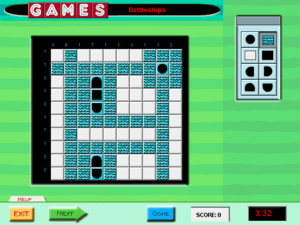

Outside and around the cryptogram UI, there’s the UI for navigating through the puzzles within a collection, and that’s where we run into real trouble. Dszquphsbnt! and Variety Cryptograms commit the same sin I previously observed in the Battleships and Paint by Numbers in the previous game: they expect you to solve each puzzle in the group in sequence, and press the “Done” button after each one to score it, but the “Next” button, which advances to the next puzzle without scoring the current one, is still available, even though there’s no way to go back once you’ve pressed it. Cryptolists spreads a single puzzle over multiple pages, one list element per page, and thus allows you to page back and forth freely with the “Next” and “Back” buttons, but it still expects you to press “Done” on every single page to get credit for it. Hitting “Done” on every page isn’t enough to finish the puzzle, though. You signal that you’re finished with a Cryptolist by pressing “Next” on the very last page, which is way too easy to do accidentally, because you’re pressing that button a lot just to see the entire puzzle.

The very worst thing, though, is the Crypto Funnies. Like Cryptolists, Crypto Funnies spreads a single puzzle over multiple pages, one page for each panel of the comic. And like Cryptolists, it lets you page around with “Next” and “Back”, and expects you to hit “Done” on each page. But this time, there doesn’t seem to be any way to signal completion. Pressing “Next” on the last page just keeps you at the last page. The only way to get out is to just quit the puzzle, which leaves no record that you ever attempted it.

Remember that there’s a final puzzle only available to people who have played all the puzzles. It looks like this is impossible to reach without cheating. So I cheated. I think it’s permissible in this case: I’m not lying to the game about my accomplishments, I’m just making it acknowledge the truth by the only means available. Luckily, the game’s record of player progress turns out to be stored as an easily-editable text file. The only complication was that I failed to realize at first that the first thing in that file is a count of the records it contains; if I didn’t increase that, anything I appended to the end would be ignored.

[Update] It turns out there is a non-cheating way to get credit for attempting the Crypto Funnies: pressing Next on the final page works if and only if you have not made any attempt at solving the puzzle. If any letters are bound, it fails. I guess this explains how the unlocking of the final puzzle passed the developer’s tests, if they performed any.

Comments(1)

Comments(1)