Costume Quest

One of the unfortunate things about the annual IF Comp for this blog is that it tends to engulf Halloween, leaving seasonally-appropriate games unplayed. But this year, throwing my already-dented schedule to the wind, I managed to play all the way through Double Fine’s Costume Quest in a single night, and through its Christmas-themed DLC Grubbins On Ice a few days later.

I can’t say for sure that I’d be saying this if I didn’t already know Tim Schafer was involved, but general the tone of the work reminds me a lot of Psychonauts, albeit shorter and lower-budget. (Which hurts it in unexpected ways: CQ was clearly designed for voice acting that it doesn’t have, with the result that text sometimes sits unskippable on the screen for the amount of time it would take to say it aloud, in a bright white speech balloon that makes it hard to focus on the generally dimly-lit world.) Both works get a lot of their humor from the juxtaposition of children acting childish and taking their childish concerns very seriously, and the same children displaying immense world-saving powers. The basic idea here is that it’s a RPG about trick-or-treating, which is an amazingly good match when you think about it. Trick-or-treating is already essentially about venturing forth to seek treasure of a sort, and the holiday provides an excuse to get monsters involved. Knocking on doors essentially takes the place of grinding, with each door harboring a random encounter, either a grown-up who gives you candy or a group of monsters you have to fight.

The costumes, now. The costumes are essentially a simplified FF5-style Jobs system. Looking back at my description of Jobs in FF5, I notice that I even described them as “like garments that you slip on to suit your current activities”. CQ takes that a bit more literally, but even in FF5, each Job came with its own distinct outfit. Costumes in CQ are mainly found through specific quests or constructed out of cheap materials like cardboard and glitter, which are found in coffin-shaped treasure chests. Once obtained, they can be swapped among your characters arbitrarily — the kids are too young for gender to be an issue here.

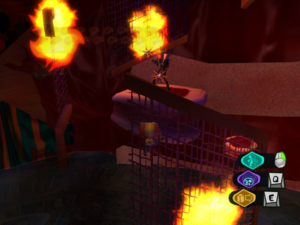

The chief effect of the costumes is in combat. Ordinarily, your characters just look like kids in cheap costumes, but whenever you enter combat, there’s a brief transformation sequence in which you become what your current costume depicts. No logical explanation for this is provided, or needed: it’s clear that the dividing line between reality and imagination is pretty thin in this game, so pretending to be a vampire or ninja or whatever is all that’s necessary to actually become one for the moment. It is, in effect, a game about playing.

The game-mechanical effect is that each costume has a distinct special move, either offensive or defensive, with its own special animation like a Final Fantasy summoning power. The robot costume, for example, has a missile barrage that hurts all enemies, while the vampire costume has a life-drain attack that restores your health. These special moves, without exception, take three combat rounds to power up. As a result, most non-boss combats end with massive overkill in exactly three rounds. Normally, this costume move is the only thing your characters can do in combat aside from simple attacks, although certain “Battle Stamps” — equippable power-ups that you can purchase with candy — give you an additional option, usually one that stuns an opponent and keeps it from attacking. Copious use of such powers makes combat downright trivial most of the time (although the end boss is nicely tricky to beat even when you’ve maxed out your power). This is why I compare the trick-or-treading to grinding. The game’s short length prevents the fights from getting too monotonous, but the fights do largely consist of watching the same animations repeatedly with a minimum of decision-making, once you’ve worked out what to do.

Even so, I generally found it disappointing to knock on a door and just get free candy without having to fight for it. This reaction is probably the opposite of what was intended, judging by the music cues.

A few of the costumes have powers that you can activate outside of combat, mainly to overcome specific obstacles: a robot costume’s wheels provide a speed boost you can use on ramps to jump over walls, a knight’s shield protects you in falling-debris fields, a pirate’s hook (seen only in the DLC) lets you slide down ziplines. I found this aspect of the game didn’t work well. It’s clearly modeled on Zelda/Metroidvania mobility powers, but somehow I always felt less empowered by my ability to overcome obstacles than inconvenienced by the necessity. Maybe it has to do with the way that the kids kept on pointing out the obstacles when I got near them, and hinting broadly at the solutions, rather than letting me discover things on my own. Also, I suppose most of the non-combat powers weren’t useable in enough different places to seem handy rather than contrived.

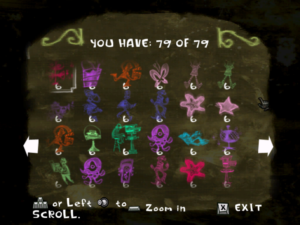

Now, I’m making a lot of complaints, but that’s because I enjoyed the game enough for anything complainable to stand out. Please understand that, although trick-or-treating is the game’s core mechanic, it’s not what you spend most of your time doing. It’s more a game of exploration and side-quests and the occasional bobbing-for-apples mini-game. The main game is divided into three areas with a great deal of symmetry in their goals — for example, each has a set of six kids hiding in various places, with a reward for finding them all. The goals are diverse and can be pursued in parallel, which goes a long way towards keeping things interesting for as long as the game lasts. And best of all, for such as me, it’s all quite completable, with a neat list of checkboxes to fill in to prove that you did absolutely everything in the game. Grubbins On Ice is essentially one larger neighborhood, with the same symmetrical sub-goals as the first three, but set in the monsters’ home world. This denatures things somewhat: adventuring in more of a pure fantasy environment lessens the juxtaposition between the fantastic and the mundane that underlies the game’s humor and its theme of the childish imagination.

That’s a point worth emphasizing, I think. This is a game that puts children into the position of hero because only the children are open-minded enough to accept what’s really going on. You can save your progress by using telephones in the game, by means of which the kids call the police, who don’t take the monster threat seriously at all, although the kids don’t seem to notice this and can keep calling back in the expectation that the police might be on the case now. The kid who sells you Battle Stamps has her stall set up in every neighborhood; in the second chapter, set in a shopping mall, she’s actually inside a store run by her father, who treats her entire operation as a pretend store, an adorable bit of make-believe of no real importance — largely because she’s concealing its significance from him. And at the end of the adventure, the party calmly trades candy at home, watched by parents who have no idea what they’ve just been through, mainly because they’re acting as if nothing unusual happened. The grownups are only aware of normal things. The children, in their naivety, have no idea what normal is, and thus don’t differentiate between the normal and the freakishly odd.

Comments(0)

Comments(0)