The Fool and His Money: Ending

Toward the end of any puzzle collection of this sort comes a point where the multitudinous bounty ends, and all you’re left with is a small number of puzzles you’re stuck on. The Fool and His Money makes an admirable go of extending puzzles through unlocking new layers, so that you can have the pleasure of solving a puzzle and still have just as many puzzles left as you started with, if not more. But even so, after I finally started slotting things into place for the climactic metapuzzle, I spent the bulk of today stuck on just two puzzles, both anagrams.

The big problem with that climactic metapuzzle is that it requires not common words, but surnames. It all ties into the game’s big theme of names and people who have lost them. The prince took away people’s names to make them more controllable; by restoring people’s names, the Fool is restoring their identities and even, in the case of the people that the Prince turned into abstract shapes, bringing them back to life. Meanwhile, the Prince’s seven minions know exactly who they are: the Fool confronts each of them by stating their name, and each replies with a brief description of its meaning and derivation, indicating that it is a being with self-knowledge and therefore power. Of course, the figures of the Tarot, such as the Hermit and the Magician, don’t have names, being archetypes rather then individuals. This may be why the Prince’s magics were able to corrupt and reverse them (such as turning the High Priestess from “the one who knows” to “the one who acts”, setting the events of The Fool’s Errand into motion — a detail I suspect was put in because Cliff Johnson knows more about the meanings of Tarot cards now than he did in 1987). There’s even some suggestion that the Prince himself is in some way a corrupted version of the Fool — they tend to mirror each other’s postures a lot, and there are at least two places in the endgame where the Prince outright replaces the Fool in a picture. But this game is too enigmatic to go for an straight-out Fight Club ending, and besides, by the end of the story, the Fool has been given a name, which should render him immune. (It’s Thomas.)

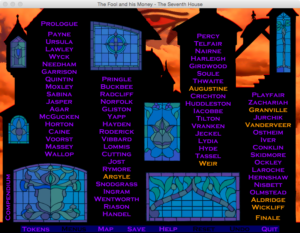

At any rate, making names rather than words is thematic, but it’s also troublesome. I’d been very pleased with the game’s choice of words in its word puzzles: even when a puzzle required very long words, it consistently chose common ones. I came to trust that the solution would always be a word I know, and that goes a long way toward keeping me going when I’m stuck. But with names, all bets are off. Just looking at the names in the main puzzle list, I see ones that I don’t think I’ve ever seen before in my life, like Voorst and Thwaite. Now, the puzzles that produce the names for the final puzzle are varied, and some of them just give you entire names without any trouble, but some of them require unscrambling of some sort, either as an anagram or by arranging some words you got from other puzzles in a grille in the correct order. And in both variants, I sometimes resorted to exhaustive permutation, with some help from reasoning backward from the anticipated solution to the metapuzzle. In the end, it turned out there was exactly one name that was completely unfamiliar to me.

I find it admirable that this wasn’t the last puzzle. The final puzzle involved going back to the main list, where a link labeled “Finale” had been available from the very beginning, leading to page that basically just reminded you that your task was not yet complete. The metapuzzle unlocks it the rest of the way, adding some more text and a puzzle, and, in accordance with good game design principles, it’s a pretty easy puzzle. It’s a type the player is familiar with by that point, pressing buttons in sequence to build up a sentence, but with a new twist, that the buttons can be pressed multiple times with different effects. But it’s pretty obvious from context what the sentence is going to be, and getting the sequence falls to exactly the same techniques as the earlier puzzles. If I recall correctly, the original Fool’s Errand had a similar post-metapuzzle moment, but had the Fool solve the simple final puzzle in a cutscene instead of letting the player do it. It’s more satisfying to do it yourself.

All in all, I’m pleased with this game, but also glad to be finished with it.

Comments(0)

Comments(0)