Blocks That Matter

It seems to me that indie games have reached a sort of turning point of inter-referentiality. In-jokey stuff abounds wherever nerds gather, but with Super Meat Boy, it escaped the confines of TIGSource and entered the marketplace. Blocks That Matter continues this trend: its story is indie-game-themed in the way that other games are fantasy-themed or mystery-themed or whatever. The premise is that its developers, a pair of wisecracking Swedes, have been kidnapped by someone who wants to play their latest game before its release. But they haven’t been working on a game, they’ve been working on a robot — a tiny cubical block-drilling-and-reassembly robot which is now their only hope for rescue.

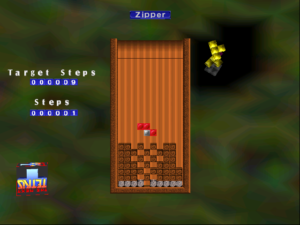

And so you puzzle-platform your way to your creators through indestructible tunnels littered with blocks in various materials, receiving instructions and banter by radio every couple of levels. The chief inspirations for this game, according to the developers, are Boulderdash, Minecraft, and Tetris. And while I can see bits of all three — Boulderdash‘s falling rocks, Minecraft‘s dig-and-build mechanic — Tetris is the single most obvious source of inspiration. Your avatar is called “Tetrobot”, and has the ability to mine blocks and then place them elsewhere — but only four at a time, in a tetromino shape. Consequently, not only do you sometimes mine a block only to immediately reconstitute it elsewhere, sometimes you place a block only to immediately re-mine it, because you only needed to place it to fulfill the tetromino requirement. Also, at one point, you get an upgrade that lets you delete blocks in continuous horizontal rows of eight or more, Tetris-style. This and the block-placement limitation are handwaved as consequences of “Pajitnov physics”.

And so you puzzle-platform your way to your creators through indestructible tunnels littered with blocks in various materials, receiving instructions and banter by radio every couple of levels. The chief inspirations for this game, according to the developers, are Boulderdash, Minecraft, and Tetris. And while I can see bits of all three — Boulderdash‘s falling rocks, Minecraft‘s dig-and-build mechanic — Tetris is the single most obvious source of inspiration. Your avatar is called “Tetrobot”, and has the ability to mine blocks and then place them elsewhere — but only four at a time, in a tetromino shape. Consequently, not only do you sometimes mine a block only to immediately reconstitute it elsewhere, sometimes you place a block only to immediately re-mine it, because you only needed to place it to fulfill the tetromino requirement. Also, at one point, you get an upgrade that lets you delete blocks in continuous horizontal rows of eight or more, Tetris-style. This and the block-placement limitation are handwaved as consequences of “Pajitnov physics”.

There are several other upgrades to your abilities over the course of the game, but other than the one in the first level that grants you basic drilling ability, they’re mostly kind of disappointing. Like, you get the ability to collect metal blocks, which were previously undrillable, and shortly afterward, undrillable crystal blocks start appearing, which are in turn made drillable by another upgrade. There are several different block materials with different properties — sand blocks that fall when unsupported, flammable wood blocks, ice blocks that slide horizontally when you try to drill them — but most materials only differ cosmetically, at least by the end.

The main thing you get from these upgrades is the ability to go back to previous levels and accomplish the goal you couldn’t always do the first time: getting the Block That Matters. Every level has exactly one, in the form of a locked treasure chest. Carry it to the level’s exit portal, and it unlocks to reveal a block representing a game that the authors like. (Some of them are indie, some not.) This strikes me as a brave thing for the authors to do, because it runs the risk that the player will say “Yeah, Lode Runner! I remember that, it was a great game! … Why am I not playing it instead of this?”

Anyway, I do think it’s ultimately a good thing that the game makes some of the Blocks That Matter inaccessible until after further upgrades, because it gives the game an element of nonlinearity. If it had been possible to collect each on the first pass at a level, I would have done so, and then wouldn’t have anything to go back to when I was stuck.

And yes, I did get stuck sometimes, for a while. There are puzzles here that require special insights into the game mechanics, like how to place blocks in a useful way in a confined space. I think the one point I was stuck on the longest was one with a small pit lined with TNT blocks, which explode a few seconds after you try to drill them. It seemed like an impossible situation: the only way to clear the way was to detonate the blocks, which you could only do by jumping into the pit, from which there was no way to escape the explosion. But in fact there was a way. It just wasn’t the sort of thing you do in most of the rest of the game.

There are actiony bits, where you have to dodge moving elements like slimes or dripping lava, but it’s mostly sedate and self-paced. Even slimes can be destroyed without dodging by dropping sand blocks on them; even lava can be stoppered by putting a stone or metal block right underneath it. Placing a tetromino involves going into a special “edit mode”, in which time is frozen. Sometimes I went into edit mode just to pause the action while I assessed my situation, but even that was usually unnecessary.

There are actiony bits, where you have to dodge moving elements like slimes or dripping lava, but it’s mostly sedate and self-paced. Even slimes can be destroyed without dodging by dropping sand blocks on them; even lava can be stoppered by putting a stone or metal block right underneath it. Placing a tetromino involves going into a special “edit mode”, in which time is frozen. Sometimes I went into edit mode just to pause the action while I assessed my situation, but even that was usually unnecessary.

There’s a certain amount of busywork involved in just collecting blocks that will be useful elsewhere, and in some levels, where there are multiple stages of puzzle, I found myself repeating the earlier stages a lot because I was making mistakes or getting killed in the later stages. There are a variety of ways a game can avoid this — checkpoints, rewind functions, etc. — but the developers here didn’t implement any such things. I hope they consider adding them if they ever do a sequel. Nonetheless, I call this a pretty good game, well worth the fraction of the bundle money I spent on it, and the few hours it took me to reach the finish and get most of the Blocks That Matter. The few I haven’t got are in the more action-oriented levels, and will probably stay there, curious though I am about what games they reveal.

Comments(1)

Comments(1)