Pool of Radiance: Same Old

I’ve really been getting into the swing of this game. Once you’re used to the stupidity of the interface, it goes pretty quickly. I’m completing multiple missions per day now, each yielding a substantial experience bonus. (Or maybe that’s just the experience for receiving the cash reward. That’s something I had almost forgotten about the AD&D rules: you get experience points for treasure, not just for defeating enemies.) There’s a nearly one-to-one correlation between missions and map sectors (16×16 segments, just like in Might and Magic), and judging by a map I found in Phlan’s library, I’ve subdued most of the map by now (barring secret dungeons).

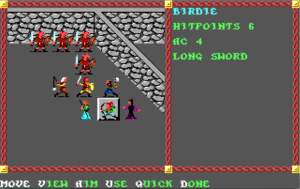

It probably helps that it’s all so familiar. Apart from the fact that it’s mostly above ground, this is very much a by-the-book D&D campaign. You’ve got your sequence of progressively-tougher humanoid opponents, starting with kobolds and goblins, working up through orcs and hobgoblins to gnolls and bugbears — all of which functionally equivalent, but rendered distinct in the mind by the way that each takes a turn at being the new, tougher-than-normal thing. At the same time, you’re also climbing a parallel ladder with the undead, starting with skeletons and zombies, moving up to ghouls and wights and so forth — which aren’t functionally equivalent, because ghouls paralyze and wights drain experience levels. 1Level drain a pretty big deal here, because the game provides no way to restore lost levels other than by re-earning the experience. It’s not clear to me whether this is because the game doesn’t support experience levels high enough to learn and cast Restoration, or whether the Restoration spell didn’t exist at the time. The latter is plausible; the first edition rules had all sorts of nastiness, including the infamous “saving throw vs death” effects. If you’ve ever played a D&D campaign from experience level 1 to 5 or so, this probably sounds very familiar to you — not just the general idea, but the specific monsters in the sequence, which most CRPGs would make up from scratch (or imitate and get slightly wrong). What I’m describing may not be how every campaign goes, but it’s certainly one of the standard openings. As the first officially licensed D&D adaptation, Pool of Radiance is basically trying to be the definitive computerized D&D experience, and that means hewing close to the typical.

It’s kind of fortunate that it’s so familiar, because sliding down that groove keeps me from having to think too hard about what I’m really doing. It’s been said many times before that the typical CRPG is about killing people and taking their stuff. 2Where “people” is taken to include any being sentient enough to engage in conversation, which applies to all of the monsters on the goblin/orc track, and some on the undead track. Here, it’s even worse: it’s about killing people and taking their land, which makes it uncomfortably close to a number of real-world situations that I’m sure the authors didn’t intend. And sure, the enemy isn’t even human, but I don’t really have to comment on the implications of that one, do I? Should I even mention that the land used to be ours long ago? Good thing morality is objectively determinable in the world of D&D or I might start to wonder who the “good guys” are. I guess this is what happens when you start to work real plot into your games.

| ↑1 | Level drain a pretty big deal here, because the game provides no way to restore lost levels other than by re-earning the experience. It’s not clear to me whether this is because the game doesn’t support experience levels high enough to learn and cast Restoration, or whether the Restoration spell didn’t exist at the time. The latter is plausible; the first edition rules had all sorts of nastiness, including the infamous “saving throw vs death” effects. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Where “people” is taken to include any being sentient enough to engage in conversation, which applies to all of the monsters on the goblin/orc track, and some on the undead track. |

Comments(2)

Comments(2)