PQ4: End

Daryl F. Gates died of cancer on April 16, 2010, three days before I started playing Police Quest 4. He was 83.

Daryl F. Gates died of cancer on April 16, 2010, three days before I started playing Police Quest 4. He was 83.

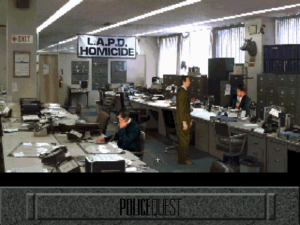

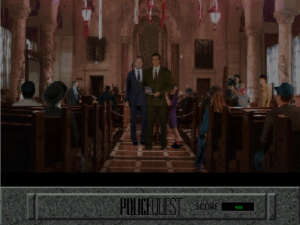

One of the biggest differences between games and real life is that games can end in victory. PQ4, as expected, ends in a moment of triumph for player character Detective Carey, his heroism in facing down the serial killer formally recognized in a ceremony where he’s given a medal by Daryl Gates himself, even if that heroism was only necessary because he deliberately put himself in a position of danger without requesting backup, and the end result was killing a man instead of making an arrest. Sonny Bonds is somewhere shaking his head sadly, but that’s the world we’re in by the end. Procedure has failed us. It’s cowboy time. The strange part is that the writers don’t seem to realize that this is what’s happening. Even in the endgame, you can get extra points by taking notes about your discoveries.

Or maybe not. It seems to me that the ending is open to another interpretation — one that would be more plausible if the game credited David Lynch or Hideo Kojima as its celebrity figurehead, but one that’s compelling enough to describe here. This will involve spoiling the ending completely, if anyone cares.

Now, recall that the victims were poisoned. The evidence about how the poison was administered was a little confusing — the autopsy reports mentioned puncture marks, as if the victim had received an injection, but also talked about the gastrointestinal tract being ruptured, which seems more consistent with an orally administered poison. Towards the end, there’s a point where you’re talking to a suspect — one Mitchell Thurman, a Norman Bates actalike who runs a dingy art cinema, apparently all by himself — and, just after you tell him that you’re investigating a murder, he offers you some tea. Taking it seems like a really bad idea, but, as with many really bad ideas, the game doesn’t provide the option of not doing it. He also offers you a free movie screening, and the end result is that you doze off in the empty theater — some images of Thurman in drag against a black background are shown, and it’s not clear if this is the movie you were watching or a dream/hallucination/premonition. Regardless, Thurman wakes you up and tells you to get out of there.

Shortly afterward, the character of the game changes — it becomes more adventure-game-like, less concerned with talking to people and more concerned with using objects on objects in sometimes unlikely combinations. (It even briefly turns into a Room Escape game, complete with first-person view and right-angle turns by mousing to the edges of the screen. This was a year before the genre-defining Crimson Room and its explosion of imitators, so, as with the proto-Dating Sim in QfG5, Sierra was anticipating things to come.) On returning to the cinema though an unlikely route, you find an unconscious woman in the seat where you fell asleep. She’s shortly taken away by Thurman, who’s wearing the same dress as in the dream sequence, and only swift action on Carey’s part saves her from becoming one more victim. (We know she’s still alive because the award ceremony at the end mentions five victims, and that’s how many have been found up to that point.)

So, what we learn from this is that Thurman’s MO involves sedating people so that they fall asleep watching movies. This is in fact what he did to Carey. So why didn’t he go through with killing him? I suppose we’re supposed to interpret his dress-up act as indicating a split personality, like in Psycho, so the Thurman who tells you to get away genuinely doesn’t want you to die, and fears what will happen when she comes out. But I have another explanation: Nothing that happens after you sit down in that darkened cinema is real. It’s all the hallucinations caused by the poisoned tea. It explains so much, and it gives the game that noir twist that I was craving in my last post. It also provides fuel for speculation. The idea that the killer is a transvestite isn’t entirely the product of Carey’s subconscious — there’s some evidence suggesting it — but the fact that his hallucination puts a woman in the place of his own unconscious body suggests gender issues of some sort. “Carey”, as one NPC points out, sounds like “Carrie”, a female name.

But as fun as it is to pursue this line of thought, I have to ask what Tim Rogers asked about Metal Gear Solid 2: Did the author intend to make the game this way? And I have to admit that I don’t think so, because I don’t think anything about this game came out as intended. Despite crediting Gates as the author, PQ4 credits Tammy Dargan as designer and writer. What that leaves for the author to do, I can’t fathom. I can’t say anything for sure about PQ4‘s development process, but this confusion of responsibility really seems like the sort of thing you’d expect in a rudderless project, where different developers are trying to take it in different directions. And that’s my impression of the game overall. There’s all this infrastructure to support investigation of a sort that just doesn’t happen — the lab reports that never come, the evidence room where you can successfully turn in one piece of evidence in the whole game, the evidence-collection toolkit that’s mainly used in that room-escape sequence at the end. It reminds me of jokes I made about doing a videogame adaptation of the movie Jarhead: it would have the most awesome tutorial ever, where you learn all sorts of devastating combo moves and the like, and then the main game would consist of sitting in a featureless desert without an enemy to fight for twenty hours.

Comments(2)

Comments(2)