Myst V: Still Trying to Get Started

I haven’t been doing much gaming for the last week or so. I’ve been busy, and expect to remain busy for another week or two. I did, however, take the time to do a little experiment. The company I work for has given me a Dell laptop — specifically, a Latitude D620. I installed Myst V on it, and sure enough, it gives a quite acceptable framerate in the part where it was bogging down to unplayability on my usual machine, which has a faster CPU and more memory. I may eventually just hook up the laptop to my monitor and mouse and play it from there, but this would be inconvenient for various reasons, so I’ll leave that as a last resort.

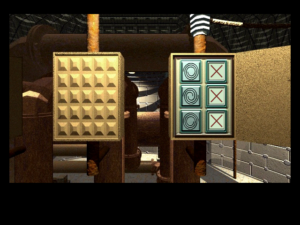

By now, I’ve played through the opening several times. After an intro sequence with a voice-over by Atrus, the game starts in the world (or “age”, as the Myst series calls them) of D’ni, in the chamber where the original Myst ended. Exploring from there, I soon met Yeesha, last seen as a little girl in Myst IV, now grown up and resembling the creepy messianic figure she appears as in Uru. 1 For those not hip to Uru: It’s basically a multi-player online Myst spin-off, set some time after the games in the series proper. The online part was cancelled shortly after launch, then the content packaged as a single-player game, and more recently the online game has been launched again. I may join Uru Live after I finish Myst V. She said a bunch of stuff that I didn’t have enough context yet to understand. I remember from Uru that Yeesha has this annoying habit of never explaining what it is she’s talking about, as if she were one of the fragmentary journals that litter the series. Then I was teleported to another “age”, where someone called Esher gave me another spiel, mainly about not trusting Yeesha. This is the point where the framerate started really degrading, and I gave up shortly afterward. (There was a tunnel leading to some content, but I didn’t spend long on it.)

So I got speeches from Atrus and Yeesha and Esher, and after hearing them repeated, I’m starting to make a little sense of them. Atrus and Yeesha said things that might mean that Atrus is dead, although they both couched it in terms vague enough to admit other possibilities: in a game where people routinely travel between worlds, to say that someone is no longer of this world doesn’t mean much. Also, Yeesha spoke of a “tablet” that “responded” to me, and which would be “released” after I did some stuff. I’m starting to think that this is a part of a certain small table-like structure of stone slabs that I was examining just before Yeesha appeared. Or maybe not. It would make sense of the claim that it “responded” to me — the table glowed or something the first time I poked it, although there didn’t seem to be any other effects, beyond triggering Yeesha’s cut-scene. It would be easier to interpret these speeches if they were written down rather than delivered orally.

Come to think of it, doesn’t the UI provide transcripts? Something to look into the next time I try it.

| ↑1 | For those not hip to Uru: It’s basically a multi-player online Myst spin-off, set some time after the games in the series proper. The online part was cancelled shortly after launch, then the content packaged as a single-player game, and more recently the online game has been launched again. I may join Uru Live after I finish Myst V. |

|---|

Comments(2)

Comments(2)