GTA: Challenges vs. Activities

Today I finished GTA3. That is, I finished the last mission, which was indeed the one described in my last post. I’m still missing three hidden packages, and the game itself calls my current state “43% complete”, but I’ve completed the story and triggered the closing credits. The credits roll over a series of views of Liberty City from high vantage points, and as they scrolled by, I tried to spot any sign of the missing Hidden Packages in the background.

Today I finished GTA3. That is, I finished the last mission, which was indeed the one described in my last post. I’m still missing three hidden packages, and the game itself calls my current state “43% complete”, but I’ve completed the story and triggered the closing credits. The credits roll over a series of views of Liberty City from high vantage points, and as they scrolled by, I tried to spot any sign of the missing Hidden Packages in the background.

Completing the final mission took many tries. At the beginning of the mission, Catalina’s goons take your weapons away, which makes the rest of the mission more difficult. You basically have to start over with just a pistol and scavenge new weapons from progressively better-armed opponents, like the whole game in miniature. After a few attempts like this, I started to wonder if it would be worthwhile to instead go back to my hideout immediately after the mission starts and pick up all the free weapons I had earned by finding hidden packages. There’s a time limit, but the hideout isn’t all that far from where you start the mission. In the end, I did not complete the mission this way, but I think that this approach would have made it much easier if my hideout had had the one weapon capable of bringing down a helicopter: the rocket launcher, earnable by finding all 100 hidden packages.

So I did some more unsuccessful scouting for hidden packages, and while I wandered looking for them, I tried out some of the things to do in Liberty City that I had been neglecting. I think these things can be meaningfully divided into two categories: challenges and activities.

By “challenge”, I mean something resembling a mission: you are assigned a goal, it is difficult to achieve that goal, and once you’ve done it, it’s done. It has some kind of permanent effect on the gameworld, at the very least deleting itself from the pool of available challenges. Optional challenges in GTA3 include Rampages, various missions not connected to the storyline and assigned by payphone, and certain special vehicles that, when entered, offer you an opportunity to earn extra cash by racing through a set of checkpoints before a timer runs out.

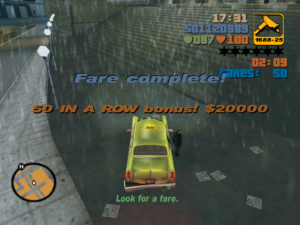

By “activity”, I mean something that has no final goal, that is not difficult, that you can do as much or as little as you please, and that, if it’s connected to the larger game at all, provides some incremental benefit rather than a single significant change to game state. In a typical CRPG, killing low-level monsters for the sake of XP would be an activity. Activities in GTA3 mostly involve service vehicles of various kinds. Steal a taxi, and you can drive passengers around for fares. Steal an ambulance and you can deliver wounded people to the hospital. Steal a fire engine and you can extinguish flaming vehicles. Steal a police car and you can go into “vigilante” mode, hunting down and killing assigned criminals. Steal an ice cream truck… well, okay, there isn’t a special activity for ice cream trucks, but there should be.

The fire engine activity is of particular interest, because while you’re doing it, the fire engine seems to be invulnerable. Since it’s also massive and powerful, this makes for the perfect opportunity to smash your way down the road, not caring what happens to the other cars. Indeed, I find that the easiest way to aim your firehose at the car that you’re supposed to be dousing is to just ram it at full speed.

The vigilante activity is also of note, because unlike the other vehicle activities, you can exit the car and continue the hunt. This is crucial, because police cars are prone to flipping over and exploding.

Now, although I tried all kinds of challenges and activities this afternoon, I spent most of my time on activities. An activity can be a nice break from a difficult challenge (such as the game’s final mission), and can give you an opportunity to hone your skills in a low-risk environment, which is really what gaming is all about in the broader world. Thus, activities are a good thing in a game, provided that they’re optional.

Comments(0)

Comments(0)