I have completed DROD: The City Beneath, seen the final revelation at Lowest Point, and learned the secret handshake, and am currently in the process of hunting down the secrets I missed (which is easier after you’ve won, because the game then tells you how many secrets there are on each level). This will probably be my last post dedicated to this game, so let me end in what seems to have become my customary way, by iterating through a list of unrelated points that I didn’t get around to making full posts about.

I have completed DROD: The City Beneath, seen the final revelation at Lowest Point, and learned the secret handshake, and am currently in the process of hunting down the secrets I missed (which is easier after you’ve won, because the game then tells you how many secrets there are on each level). This will probably be my last post dedicated to this game, so let me end in what seems to have become my customary way, by iterating through a list of unrelated points that I didn’t get around to making full posts about.

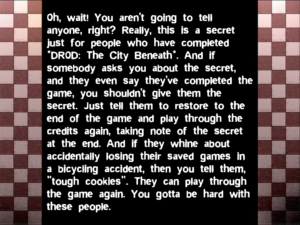

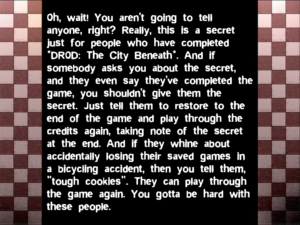

First, I wasn’t kidding about that secret handshake. When you finish the game, it gives you a little ritual you can use to identify other people who have finished it. This is kind of fun: it gives a sense that I’ve passed an initiation trial and am now a member of an elite brotherhood. The last time I got this feeling from a game was when I finished the special Grandmaster ending to Wizardry IV, and sent off for the special certificate available only to Grandmasters.

Second, I think the demo is misleading. The demo consists of the first few sections of the full game, which has a large amount of introductory material and a proportionately small amount of puzzle-solving. Since there’s no hard division between cutscene and gameplay in this game — there is a division, but it’s rather soft and permeable — this has led some people to think that this is representative of the entire game. Well, there are occasional scripted scenes throughout the game, but the first section of the City is the only area dedicated mostly to wandering around, looking at stuff, and gathering information without solving puzzles.

Third, I know I’ve already devoted a post to the improvements that TCB makes to the DROD user interface, but there are two things I haven’t mentioned that really deserve a nod. One is the “battle key”, which is one of those little things that, once you’ve tried it, you can’t imagine doing without. It’s a key (numpad + by default, although you can reconfigure that) which, when pressed, does the opposite of your previous move. That is, if your last move was to swing left, it swings right; if it was to move north, it moves south. Pressing it repeatedly alternates between two opposites — for example, swinging left, right, left, right, etc. This is exactly the sort of action you need to clear out a large number of roaches that have accumulated while your attention was elsewhere. In previous versions of the engine, you had to twiddle two keys to do this, and it was easy to miss a beat and get killed. It’s a little thing, but good UI design is built out of little things.

My other favorite new feature is the ability to right-click on any tile to identify what’s on it. This is especially useful when hunting for secret rooms. Nearly all secrets are hidden by breakable walls that look almost like the walls around them. While it’s possible to spot these by scrutinizing the graphics, I find I’m often unsure in my assessment. Sometimes it’s easy to just walk over and give the wall a poke to test it, but sometimes the uncertain spot is only reachable by, say, clearing the room of tarstuff in order to make a gate open. It’s good to know in advance if it’ll be worth the effort.

Finally, let me talk about the story a little. Beethro starts the game in search of two things: his nephew Halph, and answers. He finds Halph about halfway through the game, for all the good it does him. Answers are less forthcoming: despite the fact that the Rooted Empire’s explicit goal is knowledge, no one actually knows anything. Knowledge is valued as a treasure to be stored away in the stacks, where it sits and decays unregarded. Citizens are vat-grown for specific jobs, and, with the exception of a few rebellious individuals who help Beethro on his way, show little curiosity about anything beyond the tasks assigned them from higher up — or rather, lower down, as the seat of the Empire is at Lowest Point. Meanwhile, it becomes clearer and clearer as the story goes on that the entire system of the Empire is insane, not controlled by anything intelligent, held together only by paranoia and a willingness to not question it. As the Journey to Rooted Hold theme song put it, “Outside the walls, there wait our foes… Let each not speak that which he knows”.

In one respect, this makes Beethro’s quest futile: if the Empire is simply irrational, there can be no explanation of why it does what it does. There may be comprehensible motives for individual factions, such as the Archivists (who want complete knowledge) and the Patrons (I have no idea what they’re doing, much less why, but they seem to be opposed to the Archivists). But for the Empire as a whole, there is no reason why. So we’ll have to be satisfied with understanding how. How it all got to be this way. How it was before. The end of the game provides a very big clue (which I won’t spoil, except to note that it reminded me of something in one of the Ultima games), but we’ll have to wait for the next game to get the full story. And that’ll be several years from now. According to the end credits, the authors are going to take a break from DROD and do some other game next.

To look at him, Beethro is a lunk with a sword. But his is a world where battles are puzzles. He’s plain-spoken, even anti-intellectual at times, with no patience for the snobbery of the Empire. But when all is said and done, he’s the only person in the Empire with any inkling of what’s really going on. Which makes him a better seeker of knowledge than any of them.

So, I managed to get through the alternate exit in chapter 1, the one behind the wubba. I don’t want to give away too much, but it involved exploiting a special property of one of the useable items, a property that I had read about when I found said item, but which I had forgotten about, because it didn’t seem important at the time. When I read about it again during my second playthrough, knowing what lay ahead, it suddenly clicked. I had access to another wubba-slaying tool all along and didn’t know it.

So, I managed to get through the alternate exit in chapter 1, the one behind the wubba. I don’t want to give away too much, but it involved exploiting a special property of one of the useable items, a property that I had read about when I found said item, but which I had forgotten about, because it didn’t seem important at the time. When I read about it again during my second playthrough, knowing what lay ahead, it suddenly clicked. I had access to another wubba-slaying tool all along and didn’t know it. Comments(4)

Comments(4)