DROD RPG

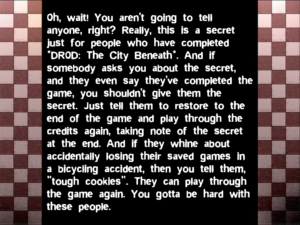

Last September, a game came out that I didn’t have time for at the time, but greatly wanted to try: DROD RPG: Tendry’s Tale, a work in the DROD setting, with familiar creatures and a plot linked to DROD: The City Beneath. The change in game mechanics is reflected by a change in protagonist: instead of Beethro, we have Tendry, a Stalwart of Tueno. In TCB, the Stalwarts charged en masse to their slaughter at the hands of the Empire, leaving only a few scattered survivors to assist Beethro with occasional puzzles. Tendry is one of those survivors.

Last September, a game came out that I didn’t have time for at the time, but greatly wanted to try: DROD RPG: Tendry’s Tale, a work in the DROD setting, with familiar creatures and a plot linked to DROD: The City Beneath. The change in game mechanics is reflected by a change in protagonist: instead of Beethro, we have Tendry, a Stalwart of Tueno. In TCB, the Stalwarts charged en masse to their slaughter at the hands of the Empire, leaving only a few scattered survivors to assist Beethro with occasional puzzles. Tendry is one of those survivors.

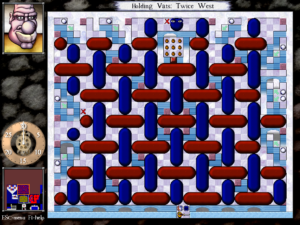

It’s always interesting to see how a game franchise weathers the translation from one genre to another, especially if the genres are greatly different. And the source material here is far from RPG-like: DROD is a puzzle game, entirely deterministic, with a combat model in which everything, including the player, has one hit point and no defense: whoever manages to strike first immediately wins. DROD RPG preserves a lot of the DROD feel simply by using the same graphics (scaled up a bit), but throws away most of the tactical puzzle-solving in favor of stat-based toe-to-toe monster-bashing.

This doesn’t mean it plays like a typical RPG. The designers have chosen to keep the determinism of the original DROD and do without any random factors in combat. Instead, you just automatically take turns trading blows with the monsters, and each blow does damage equal to the attacker’s Attack rating reduced by the defender’s Defense rating, until one of you is dead. Just by examining a monster’s stats, you can tell in advance how many hit points you’ll lose by engaging it. In fact, the game spares you the trouble of doing the math yourself and just includes the battle outcome (given your current stats) in the monster’s right-click tooltip — a sterling example of the “conveniences are nice” principle.

This extreme simplification at the tactical level means that the game is mainly played at the strategic level, where it becomes one huge resource-management puzzle. For example, sometimes you have two possible routes to a place you want to get to, one blocked by a monster, one blocked by a gate that can be unlocked with a key. (This is the lockpick-that-breaks-off-in-the-lock sort of key: they’re not specific to a single gate, but they’re consumed on use.) Either route involves some kind of expenditure of a resource, those resources being keys or hit points. You might be able to reduce or even eliminate the hit point cost, though, by finding powerups or equipment elsewhere, although you’re certainly going to pay some sort of price for such a gain. Basically, it pays to be circumspect and not rush into battles until you know what your options are.

The irony is that this is exactly the opposite of how Tendry claims to act. The Stalwarts put great stock in the courage — the level titles in the game are derived from the “rules” that the Stalwarts live by, and all the rules seem to be synonyms (“bravery”, “valor”, etc.) The occasional narration we get from our hero is full of comments about how a Stalwart always leaps feet-first into danger and recks not the cost and so forth. This is, of course, how the Stalwarts got themselves killed. I haven’t gotten very far into the game yet, but I’ve seen enough flashbacks to know that Tendry is a reluctant Stalwart, a would-be writer who was pushed into the army by his father. It’s entirely possible that he survived the massacre by being cowardly by Stalwart standards and acting like he does under player control. Or maybe not. Beethro himself is a big ugly guy who uses a Really Big Sword to solve all his problems, and was made the hero of a thinking game. So perhaps Tendry is just intended as a similar mismatch between apparent character and gameplay.

Comments(1)

Comments(1)