JtRH: Ironies

It’s only after I killed the Slayer in L7:1E using advanced techiques that I found out that there was a much easier way to do it, and that it was one I really should have noticed, because it’s basically just the exact same trick I described in the post where I complained about being unable to figure it out, just turned backward. Instead of forcing the Slayer to step on the force arrows, you walk on them yourself while approaching him. Done right, the effect is the same: the force arrow prevents the slayer from simply stepping onto your square, letting you make moves he doesn’t know how to counter.

Still, I’m past that, and galloping through the rooms at a pretty good clip again. And that means I’m well into I-don’t-remember-this-part-at-all territory. There’s a plot point on level 9 that I think is worth describing.

First, it should be noted that even though the title is Journey to Rooted Hold, journeying to Rooted Hold was never Beethro’s intention. He just wanted to get a look at what was behind that unopenable door in King Dugan’s dungeon, but then he had to go find Halph, and then he had to go down stairs a few times to escape the Slayer, and before you know it, he’s down at level 9 with no way back. There, he has an idea. He’s noticed that the levels have been heading generally southward for some time — that is, the stairs down on each level have been south of the starting location 1As in the first game, there are usually no stairs leading back up. You just go down some stairs and get deposited in a room in the next level.. So he figures they’re going to be under the neighboring city of Blorn pretty soon, and remembers a similar unopenable door in Blorn’s sewer system. Blorn isn’t where he wants to be, but at this point, anyplace where he can escape the dungeon with Halph in tow is good enough for him.

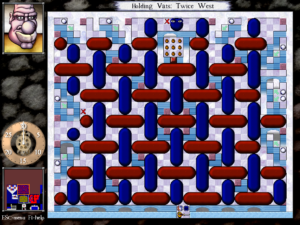

So you find the exit to the Blorn sewers, clearly labeled. It’s in the same room as the down stairs. But the Slayer is there waiting for you, and it’s clear what’s going to happen: Just at the point where Beethro is about to escape, he’s going to have to go down another floor instead. The irony of this is that the whole reason the Slayer was dispatched in the first place was that Beethro was unwilling to leave the dungeon. Now that he’s found Halph, he’s positively eager to leave, but the Slayer prevents it.

It strikes me that most of the plot of the game is driven by character flaws. Halph’s headstrong lack of cooperativeness draws Beethro down. The Slayer’s pride, his unwillingness to give up on a quarry even when the original purpose is lost, keeps him there. Even the Negotiator arguably takes some blame for the sense of superiority that makes her unwilling to listen to Beethro and therefore not actually very good at her job. Beethro himself is of course the hand that sets the dominoes in motion. His motivation? Curiosity, I guess. But if we want to peg it to a flaw, it’s the lack of consideration that led him to indulge that curiosity on a day when he was looking after Halph.

| ↑1 | As in the first game, there are usually no stairs leading back up. You just go down some stairs and get deposited in a room in the next level. |

|---|

Comments(1)

Comments(1)