SotSB: Another End Boss Down

I defeated the end boss of Secret of the Silver Blades on my second try. The winning technique hasn’t really changed since Pool of Radiance, but at least it provided a little variation after the fact: since the Dreadlord is a lich, killing his body isn’t enough. I had to find and destroy the item containing his soul, which was guarded by a second contingent of monsters. This secondary final battle wasn’t as tough as the first, lacking spellcasters as it did, which is fortunate, because I hadn’t bothered to rest up and re-buff after the first.

In the end, my entire party survived, including Vala, the NPC who I picked up about halfway through the game. Vala, who spent the last few centuries trapped in a magical box, is the last surviving member of the warrior order called the Silver Blades — or at least, she was until the rest of the party got inducted into it shortly after finding her. Despite the fact that my characters now constitute the majority of the Silver Blades, I’m still not clear on what their secret is. Perhaps it’s more that the order itself is a secret, as one might say “the crime of murder” or “the hour of noon”, or indeed “Curse of the Azure Bonds”. At any rate, Vala is the NPC whose death I described earlier, and I’m glad I went to the trouble of going back to before she died, because she occasionally made useful comments as I explored — not often enough to become annoying, either, the way a lot of hint-providing sidekicks do — and also because she was handy to have in the final battles. I really wasn’t expecting her to stick around that long; as I mentioned before, most NPCs in this series leave the party as soon as you leave the dungeon where you find them.

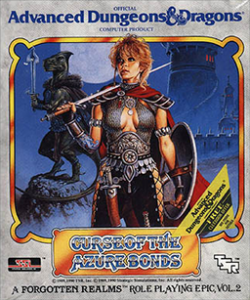

But then, this entire game is, in a sense, one big dungeon. As I surmised, there is no overland map of any kind — just a phenomenally expansive bunch of tunnels. Consequently, I have no idea where it all takes place relative to the lands around the Moonsea that form the setting for the first two games in the series. And it would have been good to have some geographical connection to the other games, because there’s very little to connect it to them otherwise. The only real links we’ve got are a couple of strikingly pointless reprised minor NPCs — the council clerk from Pool of Radiance (who I could have sworn was male back then), the Red Plume mercenary captain from Curse of the Azure Bonds (now serving as town mayor in a completely different place — just how much time passed between games, anyway?). Both are so marginal that you never learn their names. I had been expecting more because of the ending to CotAB: when you finally destroy the Pool of Radiance, Tyranthraxus gloats with his dying breath that you have, in so doing, unleashed an even greater evil, or something like that. I assume that the authors meant this as a general-purpose sequel hook that could be retconned into referring to anything, but it’s hard to see how my actions there could have had any impact on the Black Circle’s already-ongoing project to free the Dreadlord.

In fact, the strongest connection to the previous games comes in the red herrings. Remember that these games have text passages (and sometimes maps) in the manual, which the player is expected to read when referenced within the game, and not before. As a punishment for the impatient, this “Journal” contains a smattering of fake entries. I read all of SotSB‘s unused Journal entries after completing the game, and it has this whole false storyline about how Tyranthraxus managed to possess the body of a mouse just before his apparent death. There’s a tavern rumor about someone seeing a glowing mouse, a wounded adventurer who saw a glowing mouse delivering orders to a bunch of monsters (in a squeaky voice), even a revelatory villain monologue by the mouse itself. I don’t recall the previous games having fakery anywhere near as cohesive as this, although maybe the imagery just stands out more here.

Overall, this is definitely the most linear game in the series so far. Apart from a couple of quick sidequests, it’s all a single journey from point A to point B, with occasional teleporters back to point A along the way. I think the designers were trying to create a certain amount of nonlinearity by putting long gaps between the places where you find crucial items and the places where you use them — for example, the whole quest for the pieces of the Staff of Oswulf in the mines doesn’t really need to be completed until you get to the gates of the castle, which lies on the other side of the glacier crevasses and an Ice Giant settlement. It might even be more satisfying to rush forward unprepared, and only go back to pick up quest tokens when they become indispensible. (At the very least, you’d know your motivations.) But personally, my long habit in CRPGs is to proceed level by level, or place by place, being as thorough as I can in exploring one thing before going on to the next. Not only does this net you all the best treasure, it smooths the way to XP without explicit grinding. I can’t imagine I’m the only one to take this approach — pretty much everyone who’s ever ascended in Nethack does something similar — but perhaps the designers of this game had a different player in mind.

Next time, 1991. I could wrap up the entire “Epic” by moving on to Pools of Darkness. But unless the readers demand it, I think I’ll do us all a favor and move onto something else for the time being. A couple of weeks ago I thought I might be eager to see how the story ends, but SotSB has kind of ruined my faith that any kind of unified story exists.

Comments(3)

Comments(3)