Time Zone: Finishing Up

I have reached the end of Time Zone by dint of repeatedly referring to walkthroughs. I would have liked to have gotten through it unaided, of course, but I think I solved as much of the game honorably as any reasonable person could expect me to (and possibly more), and don’t regret cheating one bit. It turns out that this game rates the top slot on the Zarfian Cruelty Scale. 1It’s always struck me that Andrew Plotkin was a little brilliant to recognize that Cruelty is distinct from Difficulty. They’re related, but they’re not the same, and one can like difficult games without liking cruel ones. I knew from early on that it was easy to make irreversible mistakes — that much is clear as soon as you accidentally destroy something through time travel, which is likely to happen the very first time you travel in time. But it turns out that one of these irreversible mistakes is simply failing to wait in one location for five turns after you reach it for the first time. Go exploring and you miss a crucial event, with no indication that you missed anything (other than your eventually becoming stuck). A colleague of mine refers to the period when this game was written as “back when games hated you”. It’s a whole different ethos, and one which we’ve done well to abandon.

I have reached the end of Time Zone by dint of repeatedly referring to walkthroughs. I would have liked to have gotten through it unaided, of course, but I think I solved as much of the game honorably as any reasonable person could expect me to (and possibly more), and don’t regret cheating one bit. It turns out that this game rates the top slot on the Zarfian Cruelty Scale. 1It’s always struck me that Andrew Plotkin was a little brilliant to recognize that Cruelty is distinct from Difficulty. They’re related, but they’re not the same, and one can like difficult games without liking cruel ones. I knew from early on that it was easy to make irreversible mistakes — that much is clear as soon as you accidentally destroy something through time travel, which is likely to happen the very first time you travel in time. But it turns out that one of these irreversible mistakes is simply failing to wait in one location for five turns after you reach it for the first time. Go exploring and you miss a crucial event, with no indication that you missed anything (other than your eventually becoming stuck). A colleague of mine refers to the period when this game was written as “back when games hated you”. It’s a whole different ethos, and one which we’ve done well to abandon.

I’ve already spent far more words on this game than the game itself contains, so I’ll just say a few more things about the overall experience before I clear it from the Stack.

First of all, the map is large, and not just by Apple II standards. My maps are not exhaustive, but I count something close to a thousand rooms. However, most of them are undistinguished, and there are only a modest 30 or 40 takable obejcts. If you eliminated the padding, I think this would be a substantial but not extraordinarily large game. And in addition to mere padding, the game devotes a lot of space to red herrings: ten of the 35 2The official count is 39, but that seems to include Antarctica in every visitable time period. Antarctica, in all periods, consists of a single room where you die if you don’t just get back into the time machine immediately. It seems to be implemented as one room for all periods, and I see no reason to count it as separate zones. visitable zones are useless towards solving the game.

Secondly, there’s an awful lot of violence. Enough that it doesn’t seem in character for Roberta Williams, who’s best known for family-friendly disneyesque stuff. King’s Quest 1 in particular was known for providing violent and nonviolent solutions to the same problems (such as killing an ogre or waiting for it to fall asleep), and awarding more points for the nonviolent ones. Later episodes in the King’s Quest series eliminated the violent solutions entirely. But then, she also wrote grisly stories such as Mystery House and Phantasmagoria, which revel in their gruesomeness in a way that Time Zone doesn’t. Instead, the violence here is as casual as the violence in an action game: if someone’s in your way, you kill him, and that’s that.

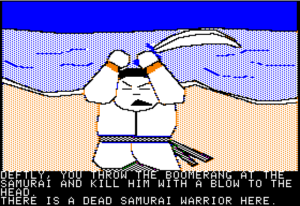

Secondly, there’s an awful lot of violence. Enough that it doesn’t seem in character for Roberta Williams, who’s best known for family-friendly disneyesque stuff. King’s Quest 1 in particular was known for providing violent and nonviolent solutions to the same problems (such as killing an ogre or waiting for it to fall asleep), and awarding more points for the nonviolent ones. Later episodes in the King’s Quest series eliminated the violent solutions entirely. But then, she also wrote grisly stories such as Mystery House and Phantasmagoria, which revel in their gruesomeness in a way that Time Zone doesn’t. Instead, the violence here is as casual as the violence in an action game: if someone’s in your way, you kill him, and that’s that.  And, since you’re globe-trotting, and the game only affords minimal descriptions and cartoony graphics, the people you kill are often ethnic caricatures. I commented before on something similar in GTA3, but it’s arguably worse here, because the author isn’t even trying to be shocking or transgressive. Instead, stereotypes are used here for the traditional reason: as an alternative to creating individual characters.

And, since you’re globe-trotting, and the game only affords minimal descriptions and cartoony graphics, the people you kill are often ethnic caricatures. I commented before on something similar in GTA3, but it’s arguably worse here, because the author isn’t even trying to be shocking or transgressive. Instead, stereotypes are used here for the traditional reason: as an alternative to creating individual characters.

Oddly, the author seems more willing to let you kill humans than animals. When you successfully attack a hostile animal, you wound it and it escapes, whereas humans are usually killed outright. At first I thought this might be a matter of the author sympathizing with the animals more (they’re not really morally culpable and all that), but now that I think about it, the only times humans leave corpses is when they’re carrying objects that you need.

Thirdly, I’d like to take back a couple of the things I said in earlier posts. The game does not make much use, if any at all, of the destruction of anachronistic objects to force different solutions to similar puzzles in different time periods. I wrote that with one particular example in mind, and that turned out to be a misunderstanding on my part. Also, contrary to both my comparison to Timequest and my statements about general time travel tropes, Time Zone does allow you to try to alter history by preventing Julius Caesar’s assassination. But if you do, Caesar dies at the appointed time anyway, stumbling over his own feet and conking his head on the floor. So you can alter history, but you can’t alter it much.

Finally, let me talk about the endgame a little. It takes place in the largest zone, and the only one to span two disks, the planet Neburon in the year 4082. The goal of the whole game is to prevent the ruler of Neburon from destroying the Earth; I didn’t mention this before because only in the endgame does it become relevant. From the point of view of the endgame, the whole purpose of the time-travelling portion of the game is to collect tools (including Caesar’s ladder) that are useful for solving the endgame’s puzzles. In a sense, this can be said of any other zone, but it’s different in the endgame. This is another one of the parts where the game hates you: past a certain point, there’s no going back, so you need to be already carrying all of the tools you’ll need, and it’s not clear which ones those are, sometimes even after you’ve seen the obstacles that require them. Due to the inventory limit, you can’t bring everything you’ve found. Due to the red herrings, you can’t be sure that you have access to everything you need yet, or which of the objects you haven’t used yet are needed. It’s all designed to make you restart the endgame repeatedly, and was probably intended to make the experience last longer — remember the author’s remark about how long it would take for anyone to solve it! But extending gameplay by making the player do things repeatedly is only a good idea if they’re things that the player enjoys doing. Action games can get away with repetitive activity (and indeed would be impossible without it), but the enjoyment in adventure games comes mainly from finding the solutions, not from typing them in after you’ve found them once. Redoing things is tolerable within limits, and restarting a game afresh after getting quite advanced can even be enjoyable, as the later parts of the game can allow one to see the earlier parts in a new light. But that’s as far as it goes.

So with the repetition and the casual violence, I’d say that the main lesson Time Zone had for the industry, apart from a warning about overcharging (it listed for $99, and was a commercial failure), is that puzzle-based adventure games don’t work like action games, and that similar techniques will leave a different impression in an adventure than in an action game. This may seem obvious now, but Time Zone isn’t alone among early adventures in using action-game features for no good reason. Even the venerable Colossal Cave adopted the arcade standard of three lives per game, despite also allowing the player to circumvent this limit by saving.

| ↑1 | It’s always struck me that Andrew Plotkin was a little brilliant to recognize that Cruelty is distinct from Difficulty. They’re related, but they’re not the same, and one can like difficult games without liking cruel ones. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | The official count is 39, but that seems to include Antarctica in every visitable time period. Antarctica, in all periods, consists of a single room where you die if you don’t just get back into the time machine immediately. It seems to be implemented as one room for all periods, and I see no reason to count it as separate zones. |

Comments(1)

Comments(1)