Stepping back a bit, I spent a substantial amount of time this fall on UFO 50, a collection of fifty retro-styled games written by a team of established indie auteurs over a span of years. There’s a Tolkien-like conceit to it, a pretense that the authors didn’t write the games, but discovered them — they were all supposedly created by a fictional company called UFOSoft, and each individual game has credits listing the individual fictional developers who worked on it. The game’s intro screen, which looks like an old crack loader, shows a series of photos of the dev team finding the fictional LX 8-bit console and its cartridges in an abandoned storage space. (The LX, by the way, has a built-in screen, handily explaining why games supposedly written in the 1980s run in 16:9.)

Although the games are retro-styled, their design sensibility, their mechanics and UX, are decidedly modern. Although many of them are clearly based on well-known games of the period, they always put some unique twist on them. And several of them draw from genres that hadn’t been invented yet when they were supposedly written, like idle games or tower defense. I’ve seen it asserted that it’s not actually appealing to nostalgia for 1980s console games, but rather nostalgia for the 2010s indie scene. And there’s something to that, not just in the content of the individual games, but in how they’re presented: as a smorgasbord. Those of us who were children in the 1980s remember games of the period as unitary things that you played monogamously until you had sucked all the entertainment value from them, because you probably weren’t going to get another until Christmas. Here, instead, you have a variety of games that you dip into as the mood strikes you, with no great commitment to finish all of them. So the overall experience resembles a games site like Newgrounds or Armor Games, or alternately, with its added framing UI, the various compilations that authors of Flash games have put on Steam since the death of Flash in the browser. It also resembles my Steam library, except that it’s of a manageable size, there’s a possibility that I’ll finish it all someday, and all of the games are highly distinct from one other, even when they’re a direct sequel to another game in the collection.

There’s some hint of a shared universe in some of the games, with recurring characters and reused assets and suggestively similar situations. Some of the links are pretty subtle, such that I wouldn’t have noticed them myself. It’s fun to overextend this and imagine that all of the games are linked, despite radically different genres: that whimsical kiddie fantasies like Magic Garden and Elfazar’s Hat exist in the same timeline as Fist Hell‘s zombie apocalypse and Avianos‘s post-human-extinction Earth. Apparently there’s an underlying mystery as well, a trail of clues that you can follow from game to game to unlock… something. I haven’t sought spoilers on this, since I found the entry point on my own and kind of want to follow it as far as I can independently. But solving the very first clue directs you to look for something in Mini & Max, a sort of adventure-platformer hybrid about exploring a closet while shrunken down to miniscule size, and this is one of the few games I haven’t made much headway in yet. It just has a level of complexity, of state you have to manage in you brain, that exceeds the threshold of what I can easily muster when I’m in smorgasbord mode.

But everyone’s going to find a different subset of the games grabs them. Here follows a list of the games that I’ve given the bulk of my attention to. The emoji indicate my progress. If you beat a game — whatever that means for that game — it awards you a golden trophy, and reveals an extra challenge that you can do, usually either 100% completion or some hidden secret goal. Beating this goal awards you cherries. Most of the games on this short list are ones that I’ve played enough to get cherries on.

🍒Party House: Probably my favorite in the collection. This is basically a deck-building game (a genre that didn’t exist in the 1980s) about throwing parties. Guests are drawn at random from the roster you’ve built, and most of them give you resources that let you buy better guests or expand your house, which lets you throw bigger parties. But some guests cause trouble, which can end the party without giving you anything. To deal with this, some guests have special abilities, like canceling out trouble or throwing out selected guests or summoning specific guests you select. You have a limited number of iterations to throw the ultimate party, which requires bringing in expensive “star” guests like aliens and mermaids. It all turns into an exercise in mastering a complex ruleset while adapting to circumstances, and, as with all the games, you have to figure it out without the aid of the manual which was presumably originally packaged with the game.

🍒Party House: Probably my favorite in the collection. This is basically a deck-building game (a genre that didn’t exist in the 1980s) about throwing parties. Guests are drawn at random from the roster you’ve built, and most of them give you resources that let you buy better guests or expand your house, which lets you throw bigger parties. But some guests cause trouble, which can end the party without giving you anything. To deal with this, some guests have special abilities, like canceling out trouble or throwing out selected guests or summoning specific guests you select. You have a limited number of iterations to throw the ultimate party, which requires bringing in expensive “star” guests like aliens and mermaids. It all turns into an exercise in mastering a complex ruleset while adapting to circumstances, and, as with all the games, you have to figure it out without the aid of the manual which was presumably originally packaged with the game.

🍒Pilot Quest: Pilot is UFOSoft’s mascot character, their Mario, although this game plays more like a Zelda. It’s an action RPG, complete with Zelda-style dungeons, but it’s also the one with idle game elements, including a rudimentary ascension system, giving you special upgrades every time you complete the game. While you’re waiting for resources to accumulate, you can go exploring to find items that help with the resource accumulation. Or you can play other games! Time passes in this game while you’re not playing it, although not when you have UFO 50 as a whole closed. So it makes sense to try this one early so it’s advancing while you try all the other games. It’s grindy, but in a way that I found appealing.

🍒Pilot Quest: Pilot is UFOSoft’s mascot character, their Mario, although this game plays more like a Zelda. It’s an action RPG, complete with Zelda-style dungeons, but it’s also the one with idle game elements, including a rudimentary ascension system, giving you special upgrades every time you complete the game. While you’re waiting for resources to accumulate, you can go exploring to find items that help with the resource accumulation. Or you can play other games! Time passes in this game while you’re not playing it, although not when you have UFO 50 as a whole closed. So it makes sense to try this one early so it’s advancing while you try all the other games. It’s grindy, but in a way that I found appealing.

🍒Warptank: An action-puzzler. In a side-view mechanized space-station environment, you control a tank that rolls left and right on whatever surface it’s on, and can additionally launch itself to the ceiling and roll around there. So it’s a bit like VVVVVV, except that you can also change your orientation by rolling over 45-degree bends in the surface you’re on. This one’s all about internalizing an unintuitive and disorienting movement system, while shooting at stuff.

🍒Warptank: An action-puzzler. In a side-view mechanized space-station environment, you control a tank that rolls left and right on whatever surface it’s on, and can additionally launch itself to the ceiling and roll around there. So it’s a bit like VVVVVV, except that you can also change your orientation by rolling over 45-degree bends in the surface you’re on. This one’s all about internalizing an unintuitive and disorienting movement system, while shooting at stuff.

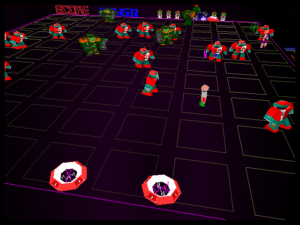

🏆Overbold: This is a twin-stick shooter in spirit, even though the LX didn’t have a dual-stick controller. I remember this being a problem for console adaptations of Robotron back in the day. Like several other UFO 50 games, Overbold takes the fairly elegant approach of letting you shoot and move in two different directions by not changing your shoot direction while you have the fire button held down. The interesting thing about the game is that it’s really all about bidding strategy. The premise is that you’re being forced to fight in an alien gladiatorial arena. Winning fights earns you cash, which you can spend on upgrades. But also, the amount of cash you win depends on how many enemies you choose to fight at a time. To survive the final round, which is the only one where you don’t get any choice about what you’re fighting, you’ll need a whole lot of upgrades. So there’s pressure to make your fights as hard as you think you can manage, to earn enough cash for the upgrades you’ll need in the end. But it’s very easy to overestimate your abilities — hence the title — and a single mistake can mean game over, putting you back at square one. It’s a very addicting loop, one that I had some difficulty pulling myself away from.

🏆Overbold: This is a twin-stick shooter in spirit, even though the LX didn’t have a dual-stick controller. I remember this being a problem for console adaptations of Robotron back in the day. Like several other UFO 50 games, Overbold takes the fairly elegant approach of letting you shoot and move in two different directions by not changing your shoot direction while you have the fire button held down. The interesting thing about the game is that it’s really all about bidding strategy. The premise is that you’re being forced to fight in an alien gladiatorial arena. Winning fights earns you cash, which you can spend on upgrades. But also, the amount of cash you win depends on how many enemies you choose to fight at a time. To survive the final round, which is the only one where you don’t get any choice about what you’re fighting, you’ll need a whole lot of upgrades. So there’s pressure to make your fights as hard as you think you can manage, to earn enough cash for the upgrades you’ll need in the end. But it’s very easy to overestimate your abilities — hence the title — and a single mistake can mean game over, putting you back at square one. It’s a very addicting loop, one that I had some difficulty pulling myself away from.

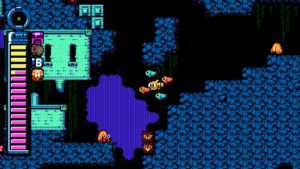

🍒Porgy: A metroidvania where you play as a cute yellow submarine. That’s about all I can say about it, and all that needs to be said. It takes a cue from Ecco the Dolphin by starting off calm and soothing but ultimately linking the marine environment to unsettling aliens. The style is mostly friendly, though, and it makes a transparent and unconvincing attempt at making the violence nonviolent by giving you torpedos that are somehow nonlethal and merely pacify the unnaturally violent sea life. You basically just have to accept this as part of the style, a nod to other 1980s games that pulled similar stuff.

🍒Porgy: A metroidvania where you play as a cute yellow submarine. That’s about all I can say about it, and all that needs to be said. It takes a cue from Ecco the Dolphin by starting off calm and soothing but ultimately linking the marine environment to unsettling aliens. The style is mostly friendly, though, and it makes a transparent and unconvincing attempt at making the violence nonviolent by giving you torpedos that are somehow nonlethal and merely pacify the unnaturally violent sea life. You basically just have to accept this as part of the style, a nod to other 1980s games that pulled similar stuff.

Rock On! Island: The only game on this short list that I haven’t beaten, this is a tower defense about cavemen fighting dinosaurs and other prehistoric animals. I just enjoy tower defenses in general, and this is a pretty difficult one, largely based around balancing your resources defending multiple pathways. Also, the player avatar can move about and attack in battle, and can be upgraded to a much more powerful attack than any of the statically-placed defenders, so a big part of the strategy is about deciding when it’s worth it to spend resources on yourself and when to spend them on more defenders. I’m pretty sure that part of why I haven’t finished it yet is that there are elements that I haven’t figured out, too — see again the implied existence of manuals that you don’t have.

Rock On! Island: The only game on this short list that I haven’t beaten, this is a tower defense about cavemen fighting dinosaurs and other prehistoric animals. I just enjoy tower defenses in general, and this is a pretty difficult one, largely based around balancing your resources defending multiple pathways. Also, the player avatar can move about and attack in battle, and can be upgraded to a much more powerful attack than any of the statically-placed defenders, so a big part of the strategy is about deciding when it’s worth it to spend resources on yourself and when to spend them on more defenders. I’m pretty sure that part of why I haven’t finished it yet is that there are elements that I haven’t figured out, too — see again the implied existence of manuals that you don’t have.

Comments(0)

Comments(0)