Daikatana: To Greece!

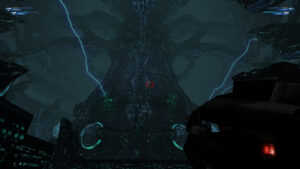

At the end of Episode 1, you finally get your hands on the game’s titular weapon, the Daikatana (Japanese for “big sword”), which is suspended in a force field apparently generated by a bunch of brains in vats. The Mishima regime has it locked away because they fear its power — the very power they used to achieve world domination. It’s not just a big sword. It’s also a time machine. When you get it, Mishima-san himself shows up with his own time-displaced Daikatana to pull a reverse Samurai Jack, expelling Hiro and his droogs from the future that is Mishima and into the legendary past.

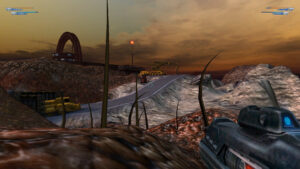

And by “legendary” I mean Greek. It’s a very videogamey, cobbled-together-without-reference sort of ancient Greece, too, the sort you’d see in Tomb Raider or Serious Sam. By leaving behind the sci-fi environments of Episode 1 (and Quake and Doom before it), we’re into the realm of not just the fanciful but the unrealistic and inconsistent. Not that I care much! The sudden environmental shift from dystopian gloom to bright sunlight and wide-open spaces and Heroic Fantasy music has been quite enjoyable.

It’s also done a lot to clarify the intent of Episode 1. It wasn’t just a continuation of the style of Doom and Quake, but an exaggeration of it, even a parody. Where Quake II had the Strogg chopping human bodies up to make cyborgs, Daikatana has similar machines processing corpses into hamburgers. Where Doom gave us a chainsaw and a double-barreled shotgun, Daikatana gives us a chainsaw-fist-glove that takes a moment to rev up and a sort of shotgun-revolver capable of firing six shells in rapid succession. These things are jokes. And the only thing that kept me from understanding this was the complaints from gamers who desperately wanted to take it all seriously.

And because those jokes only make sense in the context of an exaggeratedly brutal future, Episode 2 replaces everything. Some things are merely reskinned: instead of medical machines, for example, there are healing fountains that do the same thing. But also, you face completely different monsters, replacing the various robots, mutants, and security guards with sword-wielding skeletons, giant spiders, griffins, and the occasional shuriken-throwing ninja because Mishima still wants you dead. And you face them with a new assortment of thematic weapons, like discuses that act like the frisbees from Tron and a lightning-blasting trident. But at first, the only weapon you have is the Daikatana itself. And for all that you’ve been told about its incredible power, it’s really hard to get used to. I’ll go into more detail about it in another post, but it suddenly requires you to fight in a completely different way, getting close up and dodging back in something like the Underworld Shuffle instead of the FPS-standard constant backpedaling.

Anyway, the main surprise is that at at this point I am just unreservedly enjoying the game. Switching up the mood and gameplay helps it enormously — It may not be the underappreciated masterpiece Romero has claimed, but it’s a better sequel to Doom and Quake than Unreal II was to Unreal.

Comments(0)

Comments(0)