Hypnospace Outlaw

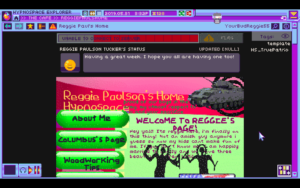

I was a Kickstarter backer for Hypnospace Outlaw, intrigued by the premise of an alternate 1990s internet simulation. And I’m glad I caught it, because it’s both one of the funniest and one of the best-designed works of interactive fiction I’ve played in some time. It’s a mockery and celebration of a bygone era, when the entire web was a glorious mess of enthusiastic amateurism, lo-res and badly-constructed by people deeply invested in dorkishness and petty nonsense, but for that very reason extremely personal and revealing in ways lacking in today’s more slickly-invented internet personas.

I was a Kickstarter backer for Hypnospace Outlaw, intrigued by the premise of an alternate 1990s internet simulation. And I’m glad I caught it, because it’s both one of the funniest and one of the best-designed works of interactive fiction I’ve played in some time. It’s a mockery and celebration of a bygone era, when the entire web was a glorious mess of enthusiastic amateurism, lo-res and badly-constructed by people deeply invested in dorkishness and petty nonsense, but for that very reason extremely personal and revealing in ways lacking in today’s more slickly-invented internet personas.

Not that Hypnospace lacks invented personas. There’s a strong current of make-believe, of people using Hypnospace as a playhouse. One user page, for example, has a bunch of “potions”, with descriptions of their effects, and gives the reader permission to take whatever they need. The potions are just images. I remember doing similar stuff back in the day, setting up a “hotel” in my college VAX-11/780 account’s directory structure, opening up write permission and inviting other people to create “rooms” with text files. That was a machine accessed through text-only terminals, but the desire for imaginary spaces runs deep. People will push the limits of whatever is possible. Hypnospace Outlaw recognizes this.

But people will also give up halfway, and HO recognizes that as well. Some of the heartiest laughs come from coming across pages where some kid just typed a bunch of failed attempts at exiting edit mode, or figured out how to change the text on the default homepage’s buttons but didn’t figure out how to make them do anything. It’s not even cruel laughter at their incompetence, really, so much as the shock of recognition. We’re not used to seeing things so blatantly half-assed in a published game, even if it is diegetically half-assed. But without it, the game would be a lie. The web of the 90s was always barely half-constructed, full of placeholders, at least as much promise as actuality. The largely-unjustified belief in that promise was crucial to the zeitgeist.

It’s odd that the game gets the feel so right, given that it was co-written by Xalavier Nelson, who isn’t old enough to remember the 90s (as he enjoys reminding people on Twitter). Nelson is the author of Screw You, Bear Dad, a game that I didn’t like much. In particular, I had harsh words for its use of “interface screw” — interfering with the player’s ability to read the text. HO indulges in interface screw as well, but at least it’s justified in-world there. If you download software from a sketchy source, it’s going to do bad things to your computer. That’s so obvious that it actually held me back from progressing in the plot for a while. There are some online hygiene habits that are so ingrained that I was reluctant to violate them in the game, even though it was clear that I was meant to have the full 90s internet experience, good and bad.

But even the malware, scams, and blatant commercialism, by being so transparent, come off as endearingly goofy — and all the moreso when they seem to be trying to take themselves seriously. There’s a whole subculture called “coolpunk” that’s centered around doing remixes of a single commercial jingle, and even though they’re presumably doing it in a spirit of irony, they’re so earnest about their irony! The original of the jingle was written by a musician called the Chowder Man, whose other works (including several other commercial jingles) can be found throughout the game, and he’s basically the king of overwrought, earnest, 90s-tinged goofiness. The Chowder Man is definitely a Hypnospace celebrity, but it’s not clear to me if he’s supposed to be an actual celebrity outside of Hypnospace. It hardly matters. Hypnospace can have its own celebrities that no one outside Hypnospace has heard of. It’s just more make-believe, right?

Like the Web, the game is broad and explorable, with offshoots and deep rabbit-holes. But it does have a main plot, with a lot of guidance about where to go and what to do in the beginning, opening up to web-search sleuthing as you become more familiar with how Hypnospace works. It impels you through this plot by giving you a job enforcing Hypnospace’s terms of service. Wait, the 90s web has terms of service? But of course Hypnospace isn’t quite our web. It’s more like a melange of AOL, Compuserve, and Geocities, and it definitely has a specific company in charge — which is the source of most of the story’s tension. The company behind Hypnospace doesn’t have the same priorities as its users. Your job as enforcer means you root out harassment and abuse, but also copyright violations, making fair-users justifiably angry at you. Surprisingly, though, this isn’t simply a matter of evil greedy corporation vs freedom-loving cyberpunks. The people behind Hypnospace are convincingly humanized, with their own personal home pages about their quirky interests that differ from those of the regular users only in that they have fewer spelling errors. If they’re making stupid decisions that alienate their users, its because they’re in over their heads. They’re a little startup in a field without a lot of historical precedent to lean on, and they genuinely don’t know what they’re doing, just like everyone else on Hypnospace.

In fact, there’s a sub-plot where the users effectively re-make the same stupid decisions as the company. At some point before the game starts, the company decided to reorganize their “zone” structure a little by combining five geek-fandom communities into one zone. The members of those communities were incensed, imputed nefarious motives to the reorg, and abandoned the combined zone to found their own “Freelands”. Which is… a combined zone, just like the one they left. Ah, but this one is under the control of the users! Well, one user. Who immediately sets himself up as a petty martinet, issuing notices to Freelands pages that don’t conform to his vision. It’s easy to see in this not just a satire of the 90s internet in particular, but a critique of power dynamics in online communities in general, both ancient and modern.

The one thing that the Freelands adds is one of those make-believe elements: instead of the standard Hypnospace zone menu, it’s set up as a multi-page map of an imaginary space, with people’s home pages embedded in it as towers and castles. This idea is later appropriated by the Hypnospace company as part of their slick new “Hypnospace 2000” initiative and presented as if they invented it. Hypnospace 2000 is frankly menacing, a visible attempt at eliminating everything vibrant about Hypnospace in order to make the whole thing more palatable to their corporate partners. It’s a small moment, but it’s the first point in that whole sub-story that made me really feel like the Freelanders really had a point, that they were being abused by the system and weren’t just overreacting to nothing. And this isn’t the only time this happens, that something is first presented as ridiculous but later turns out to have more to it. I’ll say more at the end of this post, when I get into spoilers for the ending.

But first, I have some comments on the UI and gameplay. Hypnospace is called “hypnospace” because part of the premise is that you access it via a special cyberspace headband while asleep. The internet is thus literally a shared dream, although the introductory video paints it as a productivity feature that lets you keep working 24/7 — a brilliant metaphor for the two-sided nature of wired life. And yet, even though it’s a dream, it uses the desktop metaphor. It’s a very thoroughly-implemented desktop, too. Although most of the game is played in the in-game browser, there are moments when you need various other apps — to listen to a sound file, say, or to crack an encrypted document. And these can be run from your in-game desktop, which can be customized with various desktop images that you can download from the fake internet. Desktop stickers are also a thing. You can get stickers from various sources and affix them to your desktop. And it all seems fairly pointless, because you hardly ever see your desktop. At least, I personally spent the majority of every session with Hypnospace Explorer open and maximized, and when I needed a different app, I usually used an app switcher in the main menu bar. I kind of wonder if this is deliberate, a sly bit of commentary on the wasted emphasis on desktop customizations in OS releases.

Some particular bits of the customization, such as the voice used by the optional in-game voice assistant, are put into a fake BIOS screen, which seems fittingly retro, although it occurs to me to wonder why it does. It’s not like BIOS screens have gone away. My primary game-playing machine gives a prompt to enter a BIOS menu when it boots. Ah, but how often does it boot? Mostly it just comes out of sleep mode. So I suppose I was seeing BIOS prompts a lot more in 1999 than I do now.

The game is split into multiple chapters, with time skips between them. On each skip, some pages will change while others stay the same (particularly the abandoned ones). At first, I was worried that there was no way back, and that I was going to miss content, but the final chapter has a clever way around that: it skips forward long enough that there’s a Hypnospace archival project going on, from which you can view pages from any chapter. And here’s where we get into spoilers for the ending.

I recall seeing some retweets from the developers along the lines of “Dammit, I didn’t expect this game to make me cry.” I can’t say I was moved to actual tears by the ending — possibly because I had that much warning — but I did, despite the warning, find it unexpectedly moving. It’s sort of a reverse of history: first comes the farce, then the tragedy. In an earlier chapter, people get worried about a made-up medical condition called “beef-brain” supposedly caused by excessive Hypnospace use, and a hacker collective takes advantage of their gullibility by selling them placebo images to “protect” their pages. But then an incident leaves six people dead, and Hypnospace is shuttered for years until the archival project comes along. The final chapter, then, sees you using the archives to conduct a long-overdue investigation of that incident to find out how much the Hypnospace company knew about the risks their users were facing. And at the very end, it does something brilliant. Only at that moment, after devoting your efforts to this investigation for some time, do you learn the names of the six people who died. And they’re all people you know. People who had become familiar to you through their Hypnospace presence, who you had laughed at or sympathized with or gotten annoyed at in the previous chapters.

It’s a beautiful moment because of what it shows: that this game cares about people. That’s been its attitude all along, but it’s really noticeable when it conjures characters out of a statistic. This is a good-hearted game that doesn’t need its minor characters to be flawless, or even good people, in order to be sympathetic and not deserve what happened to them. And I thank the developers for that.

Comments(0)

Comments(0)