TCB: A Puzzling Puzzle

I reached the end of The City Beneath over the weekend — it’s definitely a much easier game than Journey to Rooted Hold. But before talking about that, I’d like to describe a room in the final descent that left me baffled, even after solving it: Abyssian Fortress, 2S.

I reached the end of The City Beneath over the weekend — it’s definitely a much easier game than Journey to Rooted Hold. But before talking about that, I’d like to describe a room in the final descent that left me baffled, even after solving it: Abyssian Fortress, 2S.

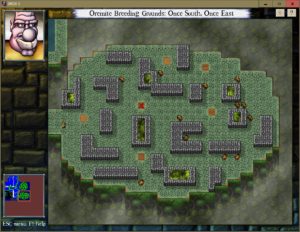

The basis of this room is that there are these nine 4×4 cells of tarstuff, three of each of the three varieties (tar, mud, and gel). The only monsters in the room are the Mothers in each cell, visible as a pair of eyes, that make the tarstuff expand every 30 turns, although the way they’re penned in here keeps them from expanding. Access out of the room is controlled by force arrows and a black gate, which only opens when all the tarstuff in the room has been cleared. And most of the floor is missing, so you have to get around by means of a 4×4 raft. So far, so straightforward. This much makes it a solid but not-too-difficult tar-clearing puzzle. The only tricky part is the gel. Gel is only vulnerable at its interior corners, but the cells here don’t have any. To get started, you have to create some by letting the gel expand onto your raft, which immobilizes the raft until it’s cleared. But even that’s just low-level tactics.

The difficulties come in with some things you have to step on to get started. First of all, there’s a disarm token, which takes away your sword. Stepping on a disarm token again restores your sword, but the force arrows around the token here prevent you from doing that. Then there’s a mimic potion, which lets you place a mimic on any clear spot on the floor. Mimics imitate your movements, and are armed with swords, so you can use that to clear the tar even when disarmed. But the circumstances suggested another possibility: what happens when a mimic steps on a disarm token? I knew that there exist things that mimics trigger just as if you had stepped on them. So I tried this, and sure enough, I got my sword back. Unfortunately, that left me in a difficult position for the next obstacle: the bridge.

Bridges are another new concept in TCB. They act kind of like level 2 of Donkey Kong: you can remove the supports by walking on them. (In fact, the game reuses the familiar trap door tiles to represent the supports.) Once the supports are all gone, the whole thing collapses, killing anything on it, including Beethro if you’re foolish enough to step back onto the bridge from the last support. In this room, there’s a bridge that’s blocking the raft from moving, and the trap door to collapse it is on the opposite end of the bridge from the raft. Getting a mimic from the disarm token all the way to the other side of the bridge without going there yourself seems impossible — the only way to enlarge the distance between yourself and a mimic is to move in a way the mimic can’t, typically by pulling it against a wall, and there are no suitably-positioned walls in that part of the room. Doing it the opposite way, collapsing the bridge personally and leaving the mimic on the raft, is feasible, but leaves you stranded on a little 2×2 platform, without enough movement room to make the mimic navigate the raft over to you. No, the easier approach, I decided, was to create the mimic on the 2×2 platform where it could free the raft, and remain swordless while it fought the tar for me.

At first, I tried just standing on the raft with the mimic while it fought the tar, but it proved difficult to protect my defenseless body this way. Eventually I got a bright idea: There’s another raft over on the right side. If I got that free, the mimic could take one raft into the fighting zones while I stand on the other, a comfortable distance away. This worked, and I cleared the level through, in effect, remote telepresence. But there were still things about the puzzle that I didn’t understand. For starters, there’s a red gate over on the right side, enclosing the platform corresponding to the one I didn’t want to get stuck on in the previous paragraph. Why is that there? It controls access to an empty space. I cleared the room without opening it. It could be a mere red herring, but DROD doesn’t usually go in for that. Or when it does, it does it with things that give you the wrong idea about a puzzle and cause you to attempt it the wrong way, not with confusing elements that don’t suggest a solution at all.

And then, after you solve the room, there’s a Challenge scroll. The challenge: Clear the room without moving the mimic over the disarm token. In other words, the thing that I had decided was impossible is apparently the normal solution. I feel like I still haven’t solved this room, despite having solved it the hard way. And I have no idea which way I solved it the first time through.

Comments(5)

Comments(5)