Machinarium: Gameplay and Hints

I’m pretty sure I’m nearing the end of this game. Like many adventures, it’s fairly short. And unlike Samorost, in which each room is a self-contained mini-adventure, Machinarium has a layout that returns on itself a lot and makes you revisit locations for different purposes and from different directions. One of the first locations has a bridge that you try to cross, only to slip on an oil slick and fall into the lower city; the same location appears again, from the other side of the bridge, much later on.

The puzzle content turns out to be mainly a mix of self-contained mini-games and environmental inventory-item use. There’s a little bit of combining of inventory items thrown in, but only in fairly obvious ways, and a little bit of Myst-style contraptioneering, but not nearly as much as you might expect given that the setting is all about fanciful machines. Some of the self-contained puzzles are old chestnuts, including one or two that even appeared in The Seventh Guest [EDIT: Looks like I’m wrong about that. See comments.], but others seem to be genuinely original, like when you have to find a minimal way to block the flow of water through a complicated tangle of branching pipes. I had fun with these puzzles, and didn’t get truly stuck on them once.

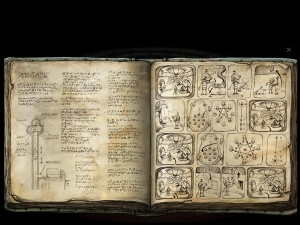

The environmental puzzles, on the other hand, I’ve got stuck on several times, either as a result of not noticing a clickable item or simply because the required action was one of those unpredictable ones that you need to just try rather than figure out. Fortunately, there’s an excellent in-game hint system, one I like so much that I’m actually kind of glad that I got stuck so that I could experience it properly. First, every scene has one free hint that displays, in a thought balloon from Josef, a picture of your ultimate goal for that scene. It’s a bit like the high-level course correction that some text adventures provide in response to the command “help” or “think”. This has never really been enough for me when I’ve resorted to hints, but I appreciate that it’s there, because if I actually had been so off-base in my thinking that all I needed was a statement of intent to put me right (as has happened in other games), I wouldn’t want or need anything more detailed. Second, you can access a more detailed depiction of every action you have to take in your current room. This is the part that I described as being “in comics form” in my last post, but let me describe it more fully now: it’s in the form of an opened book, with line drawings on the right-hand page while the left-hand page is filled with text in a made-up alphabet and perhaps an explanatory illustration that you can puzzle out the significance of, kind of like the Codex Seraphinianus. The panels depicting the actions, too, require a certain amount of interpretation — even though they’re illustrations, you have to read them — and they leave out any steps that have to be performed in a different room, such as picking up inventory items. While the absence of a particular action you were expecting in the hints for your current room can itself be a significant clue, the fact that it’s left out helps it to feel like you’re figuring out the last steps yourself instead of just following directions.

The environmental puzzles, on the other hand, I’ve got stuck on several times, either as a result of not noticing a clickable item or simply because the required action was one of those unpredictable ones that you need to just try rather than figure out. Fortunately, there’s an excellent in-game hint system, one I like so much that I’m actually kind of glad that I got stuck so that I could experience it properly. First, every scene has one free hint that displays, in a thought balloon from Josef, a picture of your ultimate goal for that scene. It’s a bit like the high-level course correction that some text adventures provide in response to the command “help” or “think”. This has never really been enough for me when I’ve resorted to hints, but I appreciate that it’s there, because if I actually had been so off-base in my thinking that all I needed was a statement of intent to put me right (as has happened in other games), I wouldn’t want or need anything more detailed. Second, you can access a more detailed depiction of every action you have to take in your current room. This is the part that I described as being “in comics form” in my last post, but let me describe it more fully now: it’s in the form of an opened book, with line drawings on the right-hand page while the left-hand page is filled with text in a made-up alphabet and perhaps an explanatory illustration that you can puzzle out the significance of, kind of like the Codex Seraphinianus. The panels depicting the actions, too, require a certain amount of interpretation — even though they’re illustrations, you have to read them — and they leave out any steps that have to be performed in a different room, such as picking up inventory items. While the absence of a particular action you were expecting in the hints for your current room can itself be a significant clue, the fact that it’s left out helps it to feel like you’re figuring out the last steps yourself instead of just following directions.  This sense is further helped by the way you access the full hints: by playing a mini-game, a crude scrolling shooter with Gameboy-style graphics in which you guide a key through spider-infested tunnels to a waiting keyhole. It’s not an engaging enough activity that I’d ever choose it when I’m not stuck, but it puts a speed bump on the process of getting hints, makes them non-free in a way that I think works better than rationing out hint tokens or whatever. It’s not too difficult once you’ve worked out how to work it, but can still take me three or four tries to get through, and that’s enough to make me feel like I’m not cheating. I earned those hints.

This sense is further helped by the way you access the full hints: by playing a mini-game, a crude scrolling shooter with Gameboy-style graphics in which you guide a key through spider-infested tunnels to a waiting keyhole. It’s not an engaging enough activity that I’d ever choose it when I’m not stuck, but it puts a speed bump on the process of getting hints, makes them non-free in a way that I think works better than rationing out hint tokens or whatever. It’s not too difficult once you’ve worked out how to work it, but can still take me three or four tries to get through, and that’s enough to make me feel like I’m not cheating. I earned those hints.

Comments(6)

Comments(6)