IFComp 2010: Ninja’s Fate

First up, a memorial piece by Hannes Schueller. Spoilers follow the break.

Read more »

First up, a memorial piece by Hannes Schueller. Spoilers follow the break.

Read more »

A while back, I wondered how I was going to squeeze in the Comp this year. At the beginning of the year, I had decided on a schedule of 25 games from the Stack, with two weeks reserved per game, leaving just two weeks of the year free — and that schedule was slipping. How was I going to fit in a month of IF?

Fortunately, the more recent games have been taking considerably less than two weeks to play. A sign of the direction the industry has taken? Or just a sign that short games don’t stay on the Stack for more than a few years? Probably a little of both. Regardless, I have plenty of time to spend on the Comp. There are a mere 26 entries this year, and Emily Short’s initial impression is that it “looks like a strong year”. I encourage my readers to play along and judge the games for themselves. Let us begin.

Gumboy‘s final level, titled “The Hell”, takes place in a system of caves with lava-drips and hovering, fire-breathing Thai demon heads (which, curiously, breathe their fire from their noses, not their mouths). I think Gumboy died more times in this level than in the rest of the game combined, but fortunately, there’s an abundance of save points. The save points are mostly situated in places where you can’t go backward, or at the very least have no reason to do so, and thus the level is effectively chopped up into a number of mini-levels.

Gumboy‘s final level, titled “The Hell”, takes place in a system of caves with lava-drips and hovering, fire-breathing Thai demon heads (which, curiously, breathe their fire from their noses, not their mouths). I think Gumboy died more times in this level than in the rest of the game combined, but fortunately, there’s an abundance of save points. The save points are mostly situated in places where you can’t go backward, or at the very least have no reason to do so, and thus the level is effectively chopped up into a number of mini-levels.

As a whole, it’s something of a recapitulation of all the special tokens and powers you’ve become familiar with over the course of the game — tokens that let Gumboy jump, make him smaller, make him stick to walls, turn him light as a balloon. There’s even a new token that turns him temporarily fireproof, something that would have had no practical use outside of The Hell. One fairly common token from before is notably missing: the one that turns him into “water”.

Eventually, you come to an empty chamber with no way out. As you roll across a particular trigger spot, a number of those demon heads suddenly appear and start firing at you. Again, I stress that there’s no way out. You can dodge the blasts — there’s a nice curved bit on one wall that you can use to get over the fireballs that move horizontally — but this just prolongs matters, because they’re going to blast again, and there’s no way out. I mean, okay, there is after a while. It’s a survival challenge: after you’ve spent a certain amount of time in there without dying, the heads disappear and are replaced with the final exit portal, which takes you back to the sunny arboreal spaces of the tutorial levels, where the game’s first non-interactive cutscene plays. Your reward for passing through The Hell: you meet Gumgirl! I laughed out loud at this, which is something few games indeed have made me do.

Still, while you’re in that chamber, there is (as usual for this game) no indication of the rules. You’re expected to just catch on. And yeah, that did in fact work. But for a while, I contemplated the possibility that this was it. An ending without triumph, where your temerity in entering The Hell is rewarded with an impossible challenge. There’s no mechanical reason why this couldn’t be the case; it’s not like it had to let you finish in order to unlock the next level, because the level-selection UI made it clear that there wasn’t one. The main thing that made me think this wasn’t the case was the thought that news of the resulting player outrage would surely have reached my ears.

It’s the most intense action sequence in a pretty tranquil game, and you know something? It’s still pretty tranquil. It’s still far from a twitch game. The heads move and fire in a regular pattern, a cycle that lasts a matter of seconds. Once you’ve found a sequence of moves that lets you live through such a cycle, all you have to do is repeat it without mistakes for enough iterations to convince the game that you can repeat it indefinitely. And that’s something best accomplished with meditative calm.

Can I just say how much I love this game? It seems like I’ve had to force myself, against my will, to make time for a lot of the games I’ve been sampling lately, even if the game is enjoyable once I’m playing it. Not so here. I’m so eager to play, I’m finding the time to get in a level or two in the morning before departing for work. I think the last time this happened was with DROD.

I think my reaction has a lot to do with the way that it just lets you play the game, without interrupting it with cutscenes or dialogue. I think of my recent experiences with Killer 7. There, a lot of the dialogue, particularly Iwazaru’s, was padded out with contentless verbiage: you’d press a button to talk to Iwazaru, and he’d say “Master!” (pause) “We’re in a tight spot!” (pause) “A very tight spot indeed! (pause)” and then he’d maybe say something important or maybe just babble nonsense at you. But I dared not skip any of it. So I suspect that when I went for a couple of days without playing, it was at least in part because a portion of my mind recoiled at the prospect of talking to Iwazaru any more.

I don’t think Gumboy will appeal to everyone the way it does to me. Some will be put off by the cutesy factor — I personally find it understated enough, and diluted with enough weird, that it doesn’t bother me. Some will dislike the gameplay. The more difficult levels produce a golf-like frustration, where you know where you have to go but can’t manage it because you can’t put just the right amount of spin on the ball or whatever. There’s a vicious cycle there: frustration breeds impatience, and impatience makes you drive Gumboy around too fast and fail even harder. This is why it’s so important that the game is so fundamentally calm.

But it’s also worth noting that the frustration and impatience produced by Gumboy‘s difficulty is of a different kind than that produced by Iwazaru’s longwindedness. The one is imposed on you by the author. The other is a consequence of the player’s actions, and therefore can be overcome. Some of the pleasure of the game comes from exactly that: the relief of overcoming frustration. This is why I prefer Gumboy‘s brand of frustration to Iwazaru’s, even though the former can actually block your progress in a game and the latter can’t.

Gumboy isn’t always a rubber ball. Certain tokens, when collected, change him. Some change his substance, turning him into what the game calls “air” or “water”, although this seems to mainly just affect his density, not his resistance to deformation. (Possibly the “air” form is more vulnerable to death by puncture, like the balloon it effectively is, but I’m not entirely convinced of this.) Others change his shape, turning him into a square or a five-pointed star, which affects how he rolls (or, on a slope, resists rolling).

Gumboy isn’t always a rubber ball. Certain tokens, when collected, change him. Some change his substance, turning him into what the game calls “air” or “water”, although this seems to mainly just affect his density, not his resistance to deformation. (Possibly the “air” form is more vulnerable to death by puncture, like the balloon it effectively is, but I’m not entirely convinced of this.) Others change his shape, turning him into a square or a five-pointed star, which affects how he rolls (or, on a slope, resists rolling).

There’s at least one other way to change Gumboy’s shape, and it’s a little disturbing.

I said that there were no enemies, but this turns out to be not quite true. There are caterpillars. At least, they’re first seen in a level titled “caterpillars”. They’re a little too small for me to identify them clearly myself, and their behavior is uncaterpillarlike in some ways, such as the way they can jump a little. They’re capable of moving around under their own power, but tend to be basically subject to gravity anyway, sliding down slopes and getting caught in depressions. Gumboy’s repulsor field affects them, which is a good thing, because you need to get them out of the way. The caterpillars appear in a series of levels where you have to shepherd a number of glass spheres around, or possibly soap bubbles — whatever they are, they’re fragile, liable to break (and respawn at their starting locations) whenever they hit a surface too hard. They’re also killed by the caterpillar’s bite.

And caterpillars do bite. You notice this the first time you hear Gumboy’s little squeals of pain on rolling over them. What I didn’t notice at first is that they were actually eating him, from the chin up. By the time I caught on, he was downright gibbous.

And caterpillars do bite. You notice this the first time you hear Gumboy’s little squeals of pain on rolling over them. What I didn’t notice at first is that they were actually eating him, from the chin up. By the time I caught on, he was downright gibbous.

Now, healing Gumboy is easy. Hitting a checkpoint seems to take care of it, as do the shape-change icons, and possibly even teleporters. I can imagine situations where being partly or even mostly eaten is even an advantage, letting you squeeze through smaller space. Nonetheless, the thought of bugs eating my face is disturbing enough that I cannot allow it. Are the caterpillars even capable of eating him completely? I don’t know, and I’m not about to find out. I’ve seen characters in videogames killed in a great many ways, including excessively gruesome ones, but this prospect is just worse somehow. I guess it shows that the decision to make him into a character rather than an inanimate object really has allowed me to identify with him.

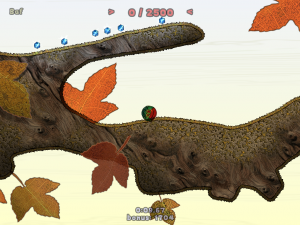

Recent years have seen the rise of the indie game, and Gumboy: Crazy Adventures is indier than many. It’s a very beautiful game, with a richly-textured environment that looks like it’s made of pieces cut out of expensive paper, embroidered fabric, and dried leaves. It’s also a very tranquil game, with no enemies, no dangers other than static environmental hazards (and many levels don’t even have that). It doesn’t even have background music to give it dramatic oomph, instead letting the gentle ambient sound of wind and water set the mood. Apparently it’s been compared a lot to Gish, which makes sense: they’re both quirky 2D physics platformers where the chief challenge is in navigating the environment. But they couldn’t be more different in tone.

Recent years have seen the rise of the indie game, and Gumboy: Crazy Adventures is indier than many. It’s a very beautiful game, with a richly-textured environment that looks like it’s made of pieces cut out of expensive paper, embroidered fabric, and dried leaves. It’s also a very tranquil game, with no enemies, no dangers other than static environmental hazards (and many levels don’t even have that). It doesn’t even have background music to give it dramatic oomph, instead letting the gentle ambient sound of wind and water set the mood. Apparently it’s been compared a lot to Gish, which makes sense: they’re both quirky 2D physics platformers where the chief challenge is in navigating the environment. But they couldn’t be more different in tone.

The protagonist, Gumboy, is essentially a rubber ball, and moves by rolling. He has a face, but most of the time, he’s rolling too fast for you to see it. I kind of wonder why they designers decided to make this ball into a character, rather than just a ball that you roll around, but I suppose it gives them an excuse to make him mutter endearingly from time to time. Your controls are limited to rolling left and right, rolling left and right faster, and sometimes jumping, although that requires a special powerup. (Usually jumping in this game means rolling up a slope fast enough that you go flying off the end.) But rolling means accelerating, and sometimes you have to accelerate just the right amount to hit an aperture without overshooting — for example, landing on a tree branch. Trying to do this in a confined space complicates things, and most surfaces are sloped and curved. Getting from point A to point B involves a lot of trial and error, but the game generally doesn’t punish you for your mistakes, or at least doesn’t add more punishment beyond natural frustration, which it tends to defuse with its lush and peaceful ambience.

The most striking thing, especially in contrast to big-budget titles, is the absence of explanation and context. There’s no opening cutscene explaining the story and who Gumboy is and why he’s having crazy adventures, no real statement of your goals beyond an arrow pointing at the next important location. There’s a series of levels in which the player has to hit a point to release a quantity of luminous dust, then another to surround Gumboy with a reddish field that repels the dust, then use this to herd a sufficient quantity of the stuff back to the start of the level, where it sticks to the exit portal and activates it. The player has to figure this out by observation and interaction, and the game has to be clear enough in its presentation to make this possible. The first time I tried playing it, I thought for sure that there must be some documentation that I didn’t have, but no. None is necessary. This makes the game a very pure example of the sort of thing that ludologists like to write about: the game as a means of experiencing the pleasure of learning mechanics through interacting with them.

Killer 7 is predicated in part on the same premise as Alan Moore’s From Hell: that serial murderers develop supernatural powers. Some of the Killer 7 personas have particular specialties, like Invisibility or Force Jump. But there are also powers they all share: they can all see the Heaven Smiles, which are invisible to ordinary humans, and they can all talk to ghosts. There are a few dead people who keep showing up repeatedly, like Travis, the “killer who got killed”. Most of the level bosses show up in levels after you kill them, too. Although they were your mortal enemies in life, they’re uniformly docile and helpful in afterlife, holding no grudge against you, which is a lot creepier than the alternative. Their combativeness was part of what made them human, even when they were thoroughly inhuman. Losing it, they seem… well, less alive. But I suppose that reducing people to things is what a hired assassin is all about. Even just contemplating the act requires dehumanizing the target.

There are a few hints dropped in the game that the Killer 7 themselves are ghosts as well, which would explain why they can’t be killed permanently. Garcian Smith, the Cleaner, is the only one who seems to have a normal existence. It’s Garcian who embarks on all the missions. Between times, we see him in his squalid little trailer home, eating pizza and enduring the shrieks and howls from wheelchair-bound Harman, who’s confined to his room and tormented by the maid. Everyone else seems to live inside the television. Garcian is the only one who has any contact with the outside world, and the only one who can’t transform into a different persona at will: every mission begins with him arriving at the site and then being replaced automatically when he passes by a security camera. He’s the only one who can really die. In short, he’s the only one who seems real.

Now, I had commented in my first post that the whole game seemed like a madman’s hallucinations. I stopped thinking about it that way after a while, because the game kept giving me more details about this strange world, and details work against doubt. One of the bosses has a long personal history with Dan Smith, and when you confront him in Dan’s persona, the game is temporarily all about Dan. This goes a long way toward convincing the player that Dan is real. You have to at least pretend that he’s real in order to follow the story. Suspension of disbelief. But the climactic mission, titled “Smile”, breaks this.

The first hint about what’s about to happen is the moon. Each mission uses a picture of the moon as a loading screen, enlarged and tinted in different bright colors. In Smile, it’s displayed for the first time in its natural grey. It’s a subtle thing, but somehow its meaning was clear: this is the mission where you come to see things as they really are. And so it was. I won’t go into detail about the final revelations, but the ending really calls into question just how much of the game actually happened. There are some recovered memories, some of which are clearly echoed in events that you earlier witnessed in cutscenes. There’s a point where you wind up back in Garcian’s trailer and Harman’s cries of agony are replaced by the sounds of machinery outside and the groaning of pipes. This is a sort of story that I think of as particularly Japanese (and even a little Buddhist): the anamnesis plot, the falling away of illusions and recovery of true self-knowledge, as seen in the likes of Silent Hill 2 and more than one Final Fantasy. It can be a very effective technique, provided the authors set it up well enough in advance, which this game certainly does.

But then the game then backtracks on this somewhat. A short final level, a sort of interactive epilogue, brings back the Heaven Smile, which otherwise disappeared from the scene without a trace when Garcian started learning the truth. A shorter, non-interactive epilogue shows Harman Smith and Kun Lan continuing their battle 100 years in the future, as if nothing had happened. You really have to read this game metaphorically sometimes, because reading it literally just doesn’t always work.

Plus, there’s just a wealth of metaphor to find. I haven’t even gotten into the political allegory. For example, one of the major plot elements is a conspiracy to control American presidential elections, with the Department of Education behind it all, because so many of the nation’s polling places are located in schools. This makes no sense if taken literally, but when you think about it, the educational establishment is very much involved in swaying elections by indoctrinating the next generation of voters. One reading of the whole game is that it’s really all about relations between Japan and America since WWII, with clues ranging from the blatant (I mean, come on, Trevor Pearlharbor?) to the less obvious (one character mentions a plan that has been in motion “for 65 years”. The game is set in 2010.) Actually, it’s not even a very speculative reading: a brewing conflict between the two nations is pretty much the literal overplot. The epilogue level has you explicitly choose sides, although your choice doesn’t seem to make a difference 100 years in the future. I mentioned before that you have to shoot at a person’s silhouette in order to enter the first mission. It turned out to be the silhouette of that mission’s end boss, and in fact the same thing is done in all subsequent missions. In the epilogue, you have to shoot at a silhouette of a flag. Because it’s just a silhouette, you can’t tell what nation it shows.

There’s a great deal of analysis of the story at GameFAQs. I can’t say I agree with all of it; much of it seems to take it for granted that everything we see in the game is supposed to be really happening, and I think the game itself discredits this notion pretty thoroughly. And ultimately, the game wants to confuse you. You can analyze it all you want, but if at the end of the day you’re not confused, you’re missing the point.

In my last post, I compared Killer 7 to Grant Morrison’s The Filth. This comparison is even more apt than I suspected at the time. One minor plot thread in The Filth concerns a bridging of realities, between the “real” world and a simplistic superhero comic. This comic is written so that people with the right equipment can delve into it, temporarily becoming characters in its pages, chiefly to exploit it by bringing the advanced technology depicted in its pages back to the real world with them. On one occasion, a fictional superhero managed to follow them out, causing no end of trouble. This breaking-through into reality of fictional characters, and superheroes in particular, is really a recurring motif in Morrison’s comics, starting with Animal Man. It’s the whole premise of Flex Mentallo.

The relevance to Killer 7: One mission is all about a Sentai team called the Handsome Men. They’re not all men, and with their Power-Rangers-like headgear, we have no reason to believe they’re handsome, but I think we can take this as part of the gag. We first see them on — where else? — television, where they’re presented as just part of an anime show, a second point where the Japanese voice acting goes undubbed. This is interrupted by a news bulletin about an assassination performed by people dressed as the Handsome Men. Shortly afterward, we’re told that the entire incident was depicted in detail in a yet-to-be-published Handsome Men comic book: the artist, Trevor Pearlharbor, is either predicting events, or causing them, summoning the Handsome Men into existence.

When you find Trevor, he’s sure that you won’t be able to kill him, because he’s just drawn a comic in which the Handsome Men stop you. He fails to take into account the mad scientist factor, the tendency of human creations to seek freedom by killing their creators. It’s done accidentally here, but if breaking script isn’t freedom, what is? (Shades of Metal Gear Solid 2 here…) So it’s a little ironic that this is the lead-in to a completely scripted fight. The two teams arrange a showdown in the middle of Times Square, a series of one-on-one duels in which each Killer 7 persona faces off against an identically-armed Handsome Man. (Ridiculously, this even means that Harman Smith’s opponent has to sit in a wheelchair to make things completely even.) Some of the duels are rigged to let you win, some to make you lose. I personally didn’t notice what was going on until the very last duel, which makes you adapt your behavior slightly before it hands you your rigged victory. So I spent most of the challenge thinking that my efforts were making a difference, when they really didn’t. Which is game design in a nutshell, isn’t it?

The game further draws the player’s attention to the artificiality of what just happened, and piles on the confusion, by ending the mission with a fake retro credits sequence in the style of earlier Capcom games. Which, I suppose, signifies victory for team Killer 7. Up to that point, the cutscenes in this mission were all anime-style, even the ones showing things like Garcian talking to his contact, which in all the other missions was handled in-engine. Anime is the Handsome Men’s territory, so a sudden assertion of videogameness returns things to Killer 7 turf. At any rate, it’s a delightful bit of player-teasing, on par with the ending to Monkey Island 2.

This isn’t the only extended bit of self-reference or genre critique in the game so far. An earlier mission started with a cutscene shown through the bad guy’s eyes, as he charged through a series of hallways with a pistol, efficiently murdering any innocent bystanders he came across with precise headshots. In other words, his acts of random violence were presented like a first-person shooter. I’m sure I could find other examples if I started looking for them, but the Handsome Men mission is the first time that it’s been the main theme, or at least the first time it’s been really obvious about it.

I don’t mean to imply that everything about Killer 7 is unusual. When I first booted it up, my reaction was “Oh, how very Capcom”. The style of the main menu, the brief textual warning about violence and “mature subject matter”, the way that it responded to my initial button press with the sound of one of the monsters (silly-sounding laughter, in this case), all reminded me of Resident Evil and similar titles. And within the game itself, the map display reminds me a lot of the level schematics normally seen in survival horror games and nowhere else.

Is Killer 7 a survival horror, then? Hardly. For one thing, you never run out of ammo. Also, survival is really pretty easy; with the exception of Garcian Smith, all of the player characters can be resurrected infinitely. But it is horror to the extent that it shows you horrible things. This is a grotesque world, where grotesque things happen. One of the boss fights is against a pair of elderly Japanese businessmen whose heads have already been blown half off, who attack by coughing pieces of brain at you. (It’s so easy to see metaphors in that.) Another of the bosses is a philanthropist who funds orphanages. First you find out that they’re killing the orphans to sell their organs, then you find out they only use the males this way, reserving the female orphans for the boss’s personal use. And even then, your guesses about how he uses them are likely to not go far enough. After you kill him, you get a glimpse of the closets where he keeps their bodies hung up like marionettes.

I’m probably making the game sound relentlessly grim. It’s not. It has a sense of humor. It’s mostly a very dark humor, but it makes some forays into wacked-out absurdist humor, which works mostly by inserting incongruous wackiness and exaggeration into the middle of the grotesquery. The most extreme example of this that I’ve seen is when you’re attacked in a parking lot by a woman in an animegao mask and schoolgirl uniform, who’s introduced with a (deliberately) clumsy approximation of a Magical Girl transformation. (This is the one place where the spoken words are still in Japanese, even in the English version.) It’s the kind of humor that produces more stunned disbelief than laughter.

I keep changing my mind about what other works this game reminds me of — which is a reasonable reaction, because it keeps abruptly changing its feel, the better to catch you off guard. At the moment, it reminds me a lot of some of Grant Morrison’s comics, particularly The Filth. There, as here, we have a series of episodes, mostly organized around a series of loathsome bad guys (each symbolizing something wrong with the world), who the heroes kill, all the while casting severe doubt about the organization behind them. One critic said about The Filth that “There’s a sense that there’s a whole other graphic novel composed of scenes cut out of this one.” That could be said about Killer 7 as well. Heck, it starts at Mission 34.

What makes a game weird?

Killer 7 has weird stuff going on in it, to be sure. But so do a lot of games. Is an assassin who transforms into someone else every time he passes in front of a video camera any stranger than a plumber who kills evil turtles by jumping on them? Isn’t it weird for a hero to periodically take breaks to smash every crate in the vicinity? If Killer 7 is noticeably strange, it’s because the designers chose to make its strangeness noticeable. I think I can identify some of the techniques they used to accomplish this.

First, the very notion of weirdness only exists in contrast to an expected normality. Smashing crates is normal enough in certain genres of game to not produce this contrast, and the likes of the Mario games exist in their own cartoon space, disconnected enough from reality that it defines its own norms. Killer 7 juxtaposes its internal madness with more conventional material — I won’t say “realistic”, because it’s not, but stuff adhering to genre norms. I’ve already described the contrast between the gameplay and an anime-styled cutscene, but it starts much earlier than that. The first two members of your team that you get a chance to see look like they stepped out of a crime movie: a cool, seen-it-all professional, a brassy, confident hitman. (The characters are communicated largely through body language, something the game excels in.) The initial cutscene, for all its stylization, supports this with its images of Garcian Smith clandestinely receiving a package from his contact. Having established this much context, then, the game proceeds to get weird.

Secondly, weirdness is uncomfortable. It teases the parts of the mind that try to fit things into familiar patterns. So I posit that increasing the sense of mental discomfort can increase the sense of the weird. This is a point I’m not entirely convinced of, but discomfort of various sorts is certainly something Killer 7 exploits, for whatever reason. There’s moral discomfort: one of the recurring NPCs is the ghost of Travis, the first person the player character killed, who makes things worse by being helpful even in death, your one consistent source of good information. Travis also casts doubt on your goals, informing you in the second mission how the man you’re trying to kill is the only thing preventing the world government from annihilating Japan. There’s bodily discomfort: a rather oogy cutscene at the beginning of mission 2 shows Harman Smith, an old man in a wheelchair, being slapped around by his maid, for reasons I have yet to see explained, except for some slight implication that it’s part of her duties. There’s discomfort at the gradually dawning realization that the Killer 7, which looked so cool in the beginning, is composed mostly of freaks and lunatics — and that they may be the best hope for their fallen world.

Thirdly, relating to the above, it seems weirder if you don’t understand what’s going on. Call it the David Lynch principle. Of course, in order for this to be effective, you have to know that you don’t understand what’s going on. Killer 7 cultivates this knowledge, giving you repeated motifs like the whole TV thing, or a particular severed head that keeps showing up in different places, as clear symbols of stuff that’s clearly important that you don’t understand yet. That maid that I mentioned: She shows up in Harman’s room, which is strangely accessible through doors in each level. Sometimes she’s in uniform, in which case she’ll save the game for you on request (using the television in the room, natch). Sometimes she’s in her street clothes, in which case she won’t help you at all. In that cutscene I mentioned, where she’s beating Harman up, she’s in street clothes at first, but instantly changes to the maid’s uniform when Garcian Smith turns out the lights. This seemed like a revelation: Aha! A consistent pattern! This applies to all the instances of Harman’s Room: she’s in uniform only if the room is dark! I understand now! Except that actually I don’t understand at all. The moment of revelation just throws the incomprehensible nonsense into relief.

All of the above applies even more strongly in Silent Hill 2. No wonder they’re both on Yahtzee’s list.