SotSB: Seeking Guidance

Hunting for these staff pieces is getting tedious. There’s not a lot of variety in the mines, or a lot of challenge either. Pretty much the only thing that can stop me now is a series of cheap KO’s from monsters with save-or-die abilities, like basilisks or wyverns. Actually, that that’s not quite right: neither of those monsters technically kills you if you fail your saving throw. The wyvern’s sting misleadingly produces the message “[character] has died”, which caused me to quit without saving when I first encountered it back in Pool of Radiance, but it’s really an effect that my cleric can cure with the Neutralize Poison spell. And while I don’t yet have the Stone to Flesh spell to undo the basilisk’s gaze, the temple back in town does.

It’s inconvenient to run back to town with a partially-petrified party, though, so basilisks are best dealt with before they can get a stare off, either by blasting them with magic or by having everyone temporarily equip mirrors in place of their shields. Only once have I failed to do this — it was a mixed encounter, basilisks and something else, and I failed to scroll the viewport far enough to notice that the basilisks were there. I won the fight, but with 2/3 of the party down. The fact that the survivors were presumably each lugging two statues wherever they went didn’t seem to slow them down, but I still wanted to end the situation as quickly as possible. So rather than go all the way back to town, I decided at first to check out the abandoned temple in the mines, where the dwarf who sent me after the staff pieces in the first place hangs out. I figured that there was an outside chance that a guy who spends his time in a temple would turn out to be a cleric, and that he might possibly be able to cast Stone to Flesh. If he wanted the staff badly enough, he might even cast it for free!

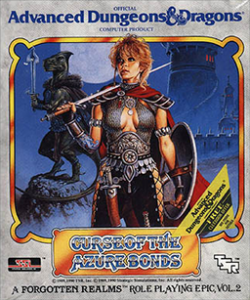

(I should note that this last point was misguided, as the temple in town also cures the party for free. This didn’t happen in the previous two games, but that’s fitting, given their plots. In Pool of Radiance, as I said before, the player characters are no one special, just a bunch of adventurers seeking their fortune, and the temples in Phlan had set up shop to share in that fortune. In Curse of the Azure Bonds, the PCs’ motives were basically selfish. But here in Secret of the Silver Blades, the heroes were summoned specifically to save the city. When you’re in town, randomly-occurring color messages continually remind you that the populace is pulling for you. Helping you along by waiving fees is part of that, unusual though it may be for a CRPG.)

When I made it back to my dwarvish taskmaster, I was dismayed to find that all he did was complain that I had only found four of the staff pieces, and then send me on my way. His failure to cure my party wasn’t even the dismaying part; I pretty much expected that. The dismaying part was that I thought I had found five pieces. I had stopped in the middle of exploring mine level six. As anticipated, I had lost track of where I had found things, and now faced the prospect of re-exploring every level I had already been through. Except it would be worse this time, because on four of those levels the staff piece was already removed, and the only way to establish this would be to search every inch.

Not liking this, I cast about for better ways, and finally did what I should have done long before: I consulted the Well of Wisdom. It did not disappoint. It didn’t tell me the exact coordinates of the remaining pieces, but it said just about everything possible short of that: what level each piece was on, what direction to take from the central shaft to find them. It turns out my missing piece is on level 3.

Advice and guidance figure big in this game, mainly because the maps are too large for the player to reasonably be expected to explore them thoroughly. And that’s not a bad thing: it makes the player replace exhaustive searches with a more deliberate, purposeful style of play. I do think it could stand to be more consistent about it, though. As far as I can tell, there’s no guidance towards finding the entrance to the mines in the first place. It’s located close enough to the Well of Wisdom that you’re expected to just run into it on your own. It certainly worked that way for me. But once that happened, it got me to stop looking for guidance, and that was bad.

Comments(0)

Comments(0)