This game is going to take longer than I first thought. I often breeze through puzzle games, and I breezed through the first 20 or so levels here, but I’ve encountered a few levels that dished out extended stuck. And not the sort of stuck where you stare at the board uncomprehendingly, with no idea of how the configuration before you might suggest enough meaning to form a plan, but the sort where achieving your goals seems mathematically impossible. The solution to this sort of stuck always comes down to some unknown or underappreciated option, some edge case that you didn’t realize was both possible and useful. So let’s take a look at what this game lets us do.

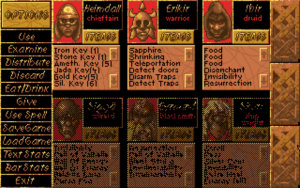

All humans can move left or right, climb ladders, and form stacks that function as human ladders. Any additional capabilities come from the tools you find lying around. There are four kinds of tool: torches, spears, ropes, and wheels. These are not permanent fixtures to the human who finds them, but can be dropped for someone else to pick up.

Torches are mainly used as keys: there are occasional burnable bushes that are impassible until torched. This provides the level designer an easy way to force the player to visit point A before point B: put a bush at point B and a torch at point A. You can also wave a torch to hold off a wandering theropod, but this is a distinctly secondary use.

Spears can kill things, including your own guys if you’re not careful, and on some levels killing a dinosaur is in fact the goal. But you don’t get the spear back after using it this way, so it’s usually a waste of a spear. The real purpose of a spear is that it lets you jump across gaps by pole-vaulting — humans cannot jump unaided. One of the first tricks you learn in this game is using a single spear to get multiple humans across a gap by having each one use it to cross, then throw it back for the next guy. It should be noted that, unlike pole-vaulting in real life, jumping in this way does not give you any additional altitude. You can’t jump from a lower platform to a higher one.

Ropes are essentially portable ladders: standing by the edge of a platform, you can lower a rope to let those below come up to where the rope-bearer is, or conversely to let humans down farther than they can safely fall. Climbing to higher ground where there isn’t a ladder generally means making a climbable stack of humans, who get left behind in the process, because no one can climb himself. But if you have a rope, no one needs to be left behind. Sometimes the trick to a level is realizing that one platform is positioned directly below another, and is therefore rope-accessible — something that isn’t necessarily obvious, because you see only a fraction of the playfield at a time, and there’s no small-scale map to give you an overview. Also, it took me some time to realize that a human climbing a rope is capable of getting off onto a platform next to it. This is reasonable, because ladders follow the same mechanic, but ladders are wide enough to actually touch the adjacent accessible ledges.

Ropes, spears, and torches can all be thrown or dropped off ledges to pass them around in ways that the humans cannot directly follow, including getting them onto a slightly higher platform, although you really can’t throw very high. The throwing mechanic is a little peculiar. First you press a button to select the “throw” action, then you press it again to start up an oscillating progress bar that determines the strength of the throw, like in various golf games, or the bonus-round minigames in the original Mortal Kombat. Jumping with a spear uses the same mechanic. I really don’t care for this system. Watching the bar means that your attention is on a UI element, not on the character it governs. We’ve had better jumping mechanics since Super Mario Brothers, but I suppose they generally rely on using the height of the jump as visual feedback, and, as mentioned, jumps in this game don’t have height.

Unless, that is, they’re done using the wheel. Wheels are the rarest of tools, and the only one you don’t pick up: you ride them, like in B. C. Wheels let you go faster, but this isn’t really an advantage — it just means it’s harder to avoid falling off of things, which is particularly troublesome because wheels can’t be carried back up ladders. They can, however, jump. Wheel jumps are most easily executed when there’s a downslope followed by a ramp, but this is not absolutely necessary. In fact, one level seems to rely on the fact that, even from a standing start, a wheel can be used to jump from a lower platform to a slightly higher one. Which is weird, because wheels are heavy — heavy enough to trigger pressure plates on their own. As such, there are sometimes puzzles developed around getting a wheel to a pressure plate, and understanding how wheels move can be key. Wheels have momentum. Wheels can be pushed without riding them, if you actually want to drop them farther than you can survive. Actually, if you time it right, you can drop farther than you can survive and still survive: all you have to do is dismount before the wheel hits the ground. I haven’t seen any puzzles that rely on this, though, and I hope I never do.

Now, most humans are identical, but there’s one special sort: the witch doctor. Witch doctors can’t use tools, although they can climb ropes, participate in stacks, and even push wheels (as proved key to one puzzle). Instead of using tools, they provide them. And they do it through human sacrifice. After selecting a victim and a type of tool, the screen goes into silhouette (on a pretty color-gradient background) and a human is transformed into a tool in a swirl of pixels, permanently reducing the human population of the level (unlike normal deaths, which yield replacements). This is a big part of why I think of this game as mean-spirited: I’ve always found the whole idea of transforming a human into an inanimate object distressing — moreso than merely killing, which at least leaves them recognizably human. To turn a person into a thing is to deny their humanity, or to deny that humanity was ever worth anything, to assert that they’re more useful as a rope or a torch. And, in the context of this game, that’s often true.

Comments(0)

Comments(0)