Tender Loving Care

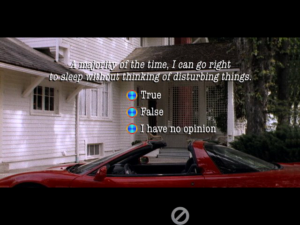

Well, the MPEG2 driver that I installed to get the cinematics in Overseer working also makes Tender Loving Care work almost perfectly. I say “almost” because there still seems to be a slight problem with the sound. Sometimes the story pauses to give the player a series of multiple-choice questions, supposedly to create a psychological profile of the player. Each question makes the mouse cursor disappear for a little while, which puzzled me until I hit a question that was read aloud by a voice-over. I surmise that this is what’s supposed to have been happening for all of the questions. But that’s not a severe enough problem to keep me from playing.

Well, the MPEG2 driver that I installed to get the cinematics in Overseer working also makes Tender Loving Care work almost perfectly. I say “almost” because there still seems to be a slight problem with the sound. Sometimes the story pauses to give the player a series of multiple-choice questions, supposedly to create a psychological profile of the player. Each question makes the mouse cursor disappear for a little while, which puzzled me until I hit a question that was read aloud by a voice-over. I surmise that this is what’s supposed to have been happening for all of the questions. But that’s not a severe enough problem to keep me from playing.

Since my last posts about this game were nearly a year and a half ago, let me recap. TLC is an interactive movie produced at the tail end of the 1990s interactive movie explosion — the sort where it’s not obvious whether it should really be considered a game or not. It’s one of the few such works to ship on DVD-ROM, although there was also a CD-ROM version for people who hadn’t adopted the new technology yet. Apparently there was also a pure DVD version — that is, something that you could play in an ordinary DVD player — but I don’t know a lot about it. I can only assume that it leaves out features from the PC versions, but honestly, I think the interaction with this game is mostly the sort that a vanilla DVD could handle with the right scripting. Basically, you alternate between two phases: watching movie clips and poking around.

The movies, which occupy far too large a portion of the total playtime to be considered mere cutscenes, tell the story of a human tragedy of some sort, involving a mentally ill woman named Allison, her husband Michael, and their live-in psychotherapist Kathryn. I don’t have all the details yet, because I’ve only played through the very beginning, but whatever happened in that house was dire enough that no one wants to live there now, according to the character who introduces the story, another psychiatrist, tangentially involved and now investigating what happened. This host figure is played by John Hurt, the work’s one big-name actor. Although he’s mentioned by the other characters, I have yet to see him interact with them. I kind of suspect that his bits were filmed afterwards, as has been known to happen in other FMV titles — probably the best-known example being Night Trap, which tried to spin a brief introduction by has-been actress Dana Plato into its chief selling point. At least Hurt is a bigger part of the game than that: he shows up at the beginning of every chapter, to comment on what you’ve seen and pose more questions about how you’re interpreting it.

The poking around is a matter of roaming freely through the house where the bulk of the action takes place, opening drawers and reading people’s diaries and the like. It’s all done in a first-person hotspot-clicking interface with FMV transitions between camera locations, kind of like The Seventh Guest without the puzzles. (As noted in my posts from last year, TLC and T7G both use the “Groovie” engine.) How exactly these scenes relate to the movies is a little mysterious. The frame-story presents everything except John Hurt’s commentary as taking place in the past and the house as currently unoccupied, but in the poking-around phases, you see the characters’ possessions as if they were still living there — and moreover, what you can find changes as the story-in-flashback progresses. The really weird moment comes if you walk into Kathryn’s room during the first poking-around segment: you meet Kathryn, who acknowledges your presence. “You’re the… viewer”, she says, a little flustered, as if unsure whether the word “player” is appropriate for a work of this sort. She then somewhat sarcastically invites you to rifle her belongings, noting that she can’t stop you. Suddenly the player seems a little more creepily voyeuristic.

Now, John Hurt’s second set of psychological profile questions asks, among other things, whether you trust Kathryn. It’s a nice little narrative trick, because once the question is in your mind, you can’t help but mistrust her a little, even if you didn’t before. In fact I did already mistrust her, if only on narratological grounds: her arrival in the house is clearly set up as the complication that pushes the story out of its ground state and into the rising action. Poking around her room afterward, I found some things that put a new perspective on what I had seen, but for the most part made her seem more trustworthy, or at least less blameworthy. For example, when she first arrives, she argues with her cab driver about the fare, claims that he’s overcharging her; ultimately, Michael pays. Reading her emails, we find a description of what happened beforehand that we didn’t see: the cab driver made some crude sexual remarks while driving, she objected, he got angry. So she wasn’t just being unreasonable with someone of a lower socioeconomic class; she had good reason to believe he was trying to punish her.

But then, given that she knows I’m there, and that I’ll be reading every email she writes, can I even trust what she says there? If she’s a manipulator, she might be manipulating me. But I don’t know yet if this is the sort of question I should even be asking in this game. If it is, I’ll be very impressed.

Comments(1)

Comments(1)