Might and Magic: Mapping the Outdoors

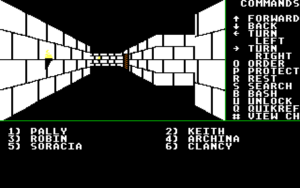

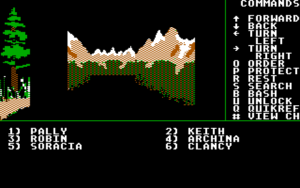

I haven’t made a lot of progress in Might and Magic yet. Mainly I’ve been exploring, trying things out, picking fights to see how tough various creatures are — learning through failure is more attractive when death has no lasting consequences. I was uneasy at first about venturing out of the starting town, but it turns out that outdoors is where the real loot is (that’s accessible to level-1 characters, anyway). So I’m contemplating the task of mapping the outdoors.

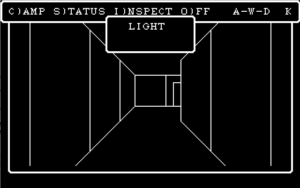

The entire world of Varn (where M&M takes place) is composed of 16×16 grids. Wizardry‘s dungeon levels were 20×20, which is a more natural number for a human, but 16 is more natural for a computer: every grid reference fits neatly into a single byte. I imagine that this compactness was appealing to the programmer who had to fit the whole of the world onto a floppy disk: although the individual map levels are smaller than Wizardry‘s, it makes up for it by having a lot more of them. Wizardry III apparently has six dungeon levels; one of the major M&M quests apparently involves six castles, each presumably with multiple levels, and that’s in addition to the sundry towns, the freestanding caves, and of course the overland map, which is a 5×4 grid of 16×16 sub-grids. (The outdoors is at a larger scale, so that an entire town fits into a single outdoor map tile.) This hierarchical nature makes the output of the Location spell a bit confusing at first: casting it from inside a town or dungeon, you get three sets of grid references, indicating your main map sector, the coordinates of the town or dungeon in that sector, and your coordinates within the town. (And the coordinates aren’t even given in terms of compass directions, but rather, as X and Y.)

You can walk between adjacent outdoor map sectors, provided there isn’t a mountain range or something in the way, but the sectors are clearly isolated units all the same. You can’t see into adjacent sectors. There always seems to be a passable-but-obscuring forest or something in the way. This makes sense, when you think about it: the whole game engine is clearly organized around dealing with only one 16×16 chunk at a time. And that means it’s reasonable to map it as isolated sectors, just like you map a dungeon one level at a time.

But I might not do it that way. When you come down to it, the world isn’t really all that big. A 5×4 grid of 16×16 tiles coms out to 80×64 — at five squares per inch (my preferred grade of graph paper), this comes out to about 16×13 inches. Paper is certainly manufactured in sheets that large, but it would probably be more convenient to use A4, which would mean spreading it out among four sheets, probably splitting it into two 32×32 sections and two 48×32 sections, leaving ample room for notes. But we’ll see how it goes. Mapping the outdoors may not even be necessary: the game comes with a map. It’s an illustrative map, and not precise to the level of map tiles, but it may well be good enough for general navigation in an environment that doesn’t play the cruel tricks that Wizardry does.

Comments(0)

Comments(0)