Everyday Shooter: End Boss

I’ve managed to survive to the end of the last song in Normal mode, but it’s clear that I haven’t really finished the game.

Level 8, “So Many Ways”, is, like level 6 and arguably level 4 before it, a level with a boss. By “boss” I just mean a unique abnormally tough enemy with lots of firepower. Bosses in shooters usually have one other attribute that these bosses don’t: they block progress. They’re generally the last thing in a level, and the way to finish level is to defeat the boss. But in Everyday Shooter, every level ends when its song is over. That’s so basic to the mechanics of the game that bosses aren’t allowed be an exception. The level 4 boss explodes into a kajillion points 1This is an estimation. You can only pick up less than thousand points before they fade away, but extrapolating from the density of those picked up, I can say with some confidence that the total number is approximately a kajillion. when killed, and, of course, stops shooting at you, which makes things a lot easier for the rest of that level. But killing it is optional. And, in fact, while the time limit imposed by the song has the effect of making it easier to pass the level, it also makes it harder to defeat the boss.

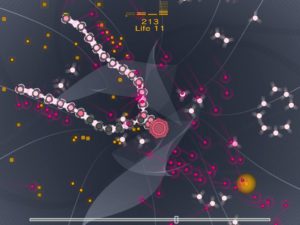

Level 8’s boss is a large circle with a pair of segmented tentacles, each segment bearing a circle that can shoot at you. The way it moves, together with its white-and-transparent color scheme, suggests jellyfish. The song is another three-section A-B-A deals like level 4; the boss drifts in at the beginning of the B section and leaves when it’s over. There isn’t nearly enough time to kill it simply by shooting at it: you pretty much have to lure it towards other objects that can be made to explode, and that’s not easy when you’re dodging its bullets. (Much of the time I accidentally detonate the thing I’m trying to lure it toward prematurely.) If you manage to defeat it, the large circle drifts to the center and becomes a point fountain. But I only know this because of Single mode, where I can play with diminished fear of death. 2Diminished, but not entirely gone. When you die, there’s a second or so before your next life begins, and that’s a second in which you’re not shooting at stuff. The song does not stop during this time. Losing a second or two probably won’t make the difference between beating the boss and not beating it, but if you’re dying frequently, it adds up. In Normal mode, I’ve managed to survive the boss, but not defeat it.

Level 8’s boss is a large circle with a pair of segmented tentacles, each segment bearing a circle that can shoot at you. The way it moves, together with its white-and-transparent color scheme, suggests jellyfish. The song is another three-section A-B-A deals like level 4; the boss drifts in at the beginning of the B section and leaves when it’s over. There isn’t nearly enough time to kill it simply by shooting at it: you pretty much have to lure it towards other objects that can be made to explode, and that’s not easy when you’re dodging its bullets. (Much of the time I accidentally detonate the thing I’m trying to lure it toward prematurely.) If you manage to defeat it, the large circle drifts to the center and becomes a point fountain. But I only know this because of Single mode, where I can play with diminished fear of death. 2Diminished, but not entirely gone. When you die, there’s a second or so before your next life begins, and that’s a second in which you’re not shooting at stuff. The song does not stop during this time. Losing a second or two probably won’t make the difference between beating the boss and not beating it, but if you’re dying frequently, it adds up. In Normal mode, I’ve managed to survive the boss, but not defeat it.

Whenever the game ends, you get an ending screen that reports how many points you accumulated and what percentage of the current level you cleared. (In Single mode, where I usually survive through the whole level, this is normally 100%.) When I passed the final song, something a little different happened: the jellyfish boss swam onto the screen again, and my completion was displayed as 99.9%. Without words, Jonathan Mak has clearly told me that I need to beat that boss to really finish the game.

I suppose I can understand the intent here. Despite its peculiarities, Everyday Shooter aspires to be a shooter in the classic mold. And in classical shooters, the player’s ultimate triumph consists of beating a difficult boss. The mechanics here mean that you can always pass a boss without beating it, so the game has to provide motivation for not doing that. It all makes sense in retrospect, but it came as something of a surprise to learn that I hadn’t beaten the game after all.

| ↑1 | This is an estimation. You can only pick up less than thousand points before they fade away, but extrapolating from the density of those picked up, I can say with some confidence that the total number is approximately a kajillion. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Diminished, but not entirely gone. When you die, there’s a second or so before your next life begins, and that’s a second in which you’re not shooting at stuff. The song does not stop during this time. Losing a second or two probably won’t make the difference between beating the boss and not beating it, but if you’re dying frequently, it adds up. |

Comments(0)

Comments(0)