Penumbra: End of the Overture

Penumbra: Overture ends inconclusively, which I suppose is its right, as the start of a series. There are certainly loathsome things in the depths — there are a couple of harrowing chase scenes involving gigantic annelids that remind me of D&D‘s Purple Worms — but the one character who talks to you is convinced that there’s something worse beyond the sealed door at the game’s very end.

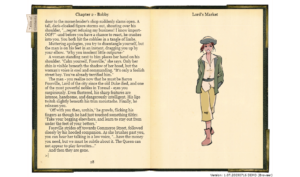

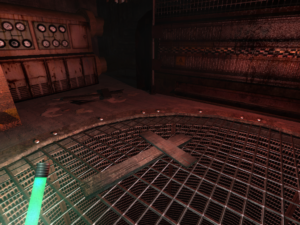

About that one NPC: He calls himself “Red”, and you never meet him directly; the closest you ever get to him is the other side of an unopenable door. He communicates with you by radio (don’t ask me how that works in a mine). He’s been trapped in the mine for a long time, and has gone quite mad, and talks very oddly 1At one point he says “There is much that should leave my throat box now, but words elude me”, which immediately made me think of “My blood pumper is wronged!” and is apparently a cannibal as well, if his stilted rantings are to be believed. But he talks as if he expects you to come meet him (despite the obvious danger), and his messages provide you with cryptic guidance through most of the game. And in the end, you kill him. Or he uses you to kill himself — he admits that he really guided you to him for that specific purpose, because the entities that share his head won’t let him do the deed himself. He’s locked himself in an incinerator, along with a key you need to open that final door, the one he desperately wants to remain closed. And it’s a peculiar moment, one of those uncomfortable places where you hesitate to go where the game is leading you. The floor of the room is littered with crude planking crosses — one of the writeups at Gamefaqs sees this as evidence that Red is a vampire, but that interpretation strikes me as bizarre and out-of-place; more likely it’s intended as a somewhat confusing comparison of Christ’s self-sacrifice to Red’s suicide-by-proxy, implicitly casting the player in the role of Judas. There’s definitely a sense of agency about turning the furnace on — you can choose to just poke around avoiding the issue for long as you want, but the consequence of not doing it is that you can’t finish the game and get stuck there forever in the bottom of the mine, just like Red, which presumably means you have a lifetime of eating rats and losing your mind to look forward to. So I make the unpleasant choice.

About that one NPC: He calls himself “Red”, and you never meet him directly; the closest you ever get to him is the other side of an unopenable door. He communicates with you by radio (don’t ask me how that works in a mine). He’s been trapped in the mine for a long time, and has gone quite mad, and talks very oddly 1At one point he says “There is much that should leave my throat box now, but words elude me”, which immediately made me think of “My blood pumper is wronged!” and is apparently a cannibal as well, if his stilted rantings are to be believed. But he talks as if he expects you to come meet him (despite the obvious danger), and his messages provide you with cryptic guidance through most of the game. And in the end, you kill him. Or he uses you to kill himself — he admits that he really guided you to him for that specific purpose, because the entities that share his head won’t let him do the deed himself. He’s locked himself in an incinerator, along with a key you need to open that final door, the one he desperately wants to remain closed. And it’s a peculiar moment, one of those uncomfortable places where you hesitate to go where the game is leading you. The floor of the room is littered with crude planking crosses — one of the writeups at Gamefaqs sees this as evidence that Red is a vampire, but that interpretation strikes me as bizarre and out-of-place; more likely it’s intended as a somewhat confusing comparison of Christ’s self-sacrifice to Red’s suicide-by-proxy, implicitly casting the player in the role of Judas. There’s definitely a sense of agency about turning the furnace on — you can choose to just poke around avoiding the issue for long as you want, but the consequence of not doing it is that you can’t finish the game and get stuck there forever in the bottom of the mine, just like Red, which presumably means you have a lifetime of eating rats and losing your mind to look forward to. So I make the unpleasant choice.

There’s one more slight detour before you can get through that final game-ending door, and that’s going into Red’s living quarters. You get to see how this unfortunate man lived, and the things he surrounded himself with, and suddenly the dominant emotion isn’t fear but sadness. A letter reveals that he’s been trapped for 30 years, since the age of 14. And that, for me, is the emotional climax of the game. Actually going through the forbidden door and getting jumped in the dark by persons unknown is denouement.

And that’s probably where I’ll leave it for a while. Near the end, I started having those graphics card issues I’ve been having lately. Taking the system apart and blowing the dust out seems like it might have helped me get through the ending, but I want to do a fuller investigation before I start any more graphically-intensive titles.

| ↑1 | At one point he says “There is much that should leave my throat box now, but words elude me”, which immediately made me think of “My blood pumper is wronged!” |

|---|

Comments(0)

Comments(0)