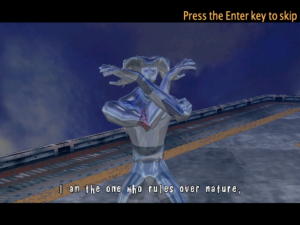

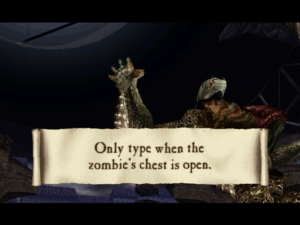

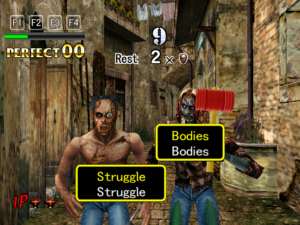

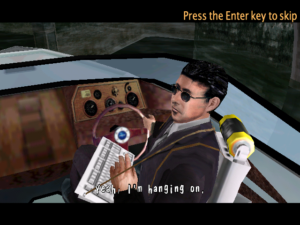

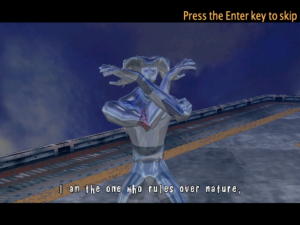

In the final level of The Typing of the Dead, the rotting corpses give way to what look more like artificial life forms or androids, grey-skinned and sporting built-in lightsabres and other superpowers. The advanced tech doesn’t stop them from just standing there like ninnies and letting you type at them for a while before they attack, though. That’s just essential to the way the game is played, especially since the phrases you type are getting pretty long by that point, but it fit the zombies better, because you expect zombies to react slowly. The end boss, the Emperor (the bosses are all named for tarot cards), is even more artificial-looking, a demon made of clear plastic. According to its creator (in an unbelievably awkwardly-dubbed cutscene), it was engineered to solve the world’s ecological crisis by ruling over humanity. Maybe this was less stupid in the original Japanese, maybe not. Some people have said that the schlockiness of the House of the Dead 2 material complements the game’s campy and self-mocking sense of humor. I just say that the cutscenes are not a significant part of the experience, and skippable.

In the final level of The Typing of the Dead, the rotting corpses give way to what look more like artificial life forms or androids, grey-skinned and sporting built-in lightsabres and other superpowers. The advanced tech doesn’t stop them from just standing there like ninnies and letting you type at them for a while before they attack, though. That’s just essential to the way the game is played, especially since the phrases you type are getting pretty long by that point, but it fit the zombies better, because you expect zombies to react slowly. The end boss, the Emperor (the bosses are all named for tarot cards), is even more artificial-looking, a demon made of clear plastic. According to its creator (in an unbelievably awkwardly-dubbed cutscene), it was engineered to solve the world’s ecological crisis by ruling over humanity. Maybe this was less stupid in the original Japanese, maybe not. Some people have said that the schlockiness of the House of the Dead 2 material complements the game’s campy and self-mocking sense of humor. I just say that the cutscenes are not a significant part of the experience, and skippable.

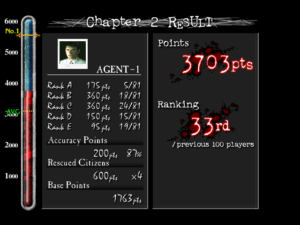

The first time I reached this point of the game, I had only a few remaining lives, which Emperor Perspex quickly removed. The game does some dynamic difficulty adjustment, at least for bosses: after you get killed a few times in succession, it starts using easier words. But in order to take advantage of this, you need lives to waste. So after my first attempt, I resolved to earn enough coins to play with 9 continues instead of 5.

There are five coins to be earned on each level, and each of the five is earned in a different way. You can make it easier to get particular coins by adjusting your approach to the game. For example, one coin on each level is earned by completing the level without any continues, and is most easily earned by setting the difficulty level to “Very Easy” and giving your top priority to avoiding damage, even if it means letting civilians die. Another is earned for scoring above a certain threshhold (the threshhold varies from level to level). This is best accomplished by setting the difficulty to “Very Hard” — which confers some kind of score bonus — and giving the civilians top priority — who cares if you lose lives yourself, saving those guys is worth a lot of points! A third coin comes from getting an “A” rating on a certain number of words. Ratings are based on how fast you type, but only the time from when type the first letter counts. So getting lots of A’s involves refraining from initiating attacks until you’re ready to type an entire word in a burst, which can mean ignoring both your health and the civilians.

This kind of strategizing may be missing the point of the game: you’re supposed to win through typing prowess, not through gaming the system. But it kept me interested enough to keep on playing, by giving me goals to strive for that seemed easier than trying to fight Emperor Plexiglass again. When I had my 9 continues, I made another run for the end. Ironically, by then I’d had enough practice that I only needed 4.

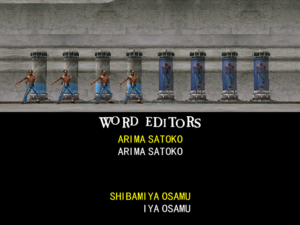

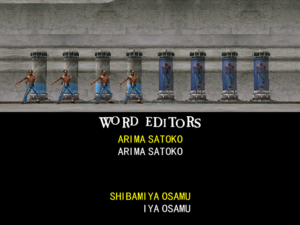

After the ending, there’s an interactive credits sequence: as the names of the developers scroll by, you can type them. Typing an entire section of the credits before it scrolls away releases a zombie from a bacta tank, and the released zombies dance to the background music, forming a chorus line of the dead. I found this bonus segment unexpectedly difficult, because the names are mostly Japanese, and Japanese uses different letter patterns than those the game trains you in — not many English words contain the sequence “ryo”, for example.

After the ending, there’s an interactive credits sequence: as the names of the developers scroll by, you can type them. Typing an entire section of the credits before it scrolls away releases a zombie from a bacta tank, and the released zombies dance to the background music, forming a chorus line of the dead. I found this bonus segment unexpectedly difficult, because the names are mostly Japanese, and Japanese uses different letter patterns than those the game trains you in — not many English words contain the sequence “ryo”, for example.

Anyway, the game works! I can totally touch-type now, with punctuation and everything! It’s pleasing to be able to take a skill away from this experience; somehow, it’s always the weird games that are life-changing. Any game with a twitch element teaches you a skill, really, but usually it’s a skill that’s only applicable in playing that game, or sometimes other similar games. And this is definitely a twitch game — when I was at my best, I was typing from my brainstem. When I was at my worst, I was flailing at the keyboard madly, too panicked to see what I was doing wrong (usually something stupid like still trying to find a key I had already typed). That sense of panic, and the ability to overcome it, is something that you just don’t get from ordinary typing practice. I’d guess that even Mavis Beacon doesn’t provide it. No, if you really want to learn to type, what you need is zombies. Seriously.

Comments(1)

Comments(1)