I mentioned before that I own three games that are based on French comic books, but this turns out not to be true. Rather, I own one game based on a French comic book (Druillet’s Salammbo), and two games based on Belgian comic books. No coincidence, either: the same artist provided the source material for both. One of them, XIII, has been off the Stack for some time. The other, Thorgal’s Quest, really should have been finished long ago too — it’s essentially a one-sitting game — but I took a break in the middle, and by the time I got back to it I had activated the nVidia glitch and made the game unplayable. (Even with my new graphics card, there are occasional video problems and even crashes, but nothing that couldn’t be overcome by saving regularly.)

I mentioned before that I own three games that are based on French comic books, but this turns out not to be true. Rather, I own one game based on a French comic book (Druillet’s Salammbo), and two games based on Belgian comic books. No coincidence, either: the same artist provided the source material for both. One of them, XIII, has been off the Stack for some time. The other, Thorgal’s Quest, really should have been finished long ago too — it’s essentially a one-sitting game — but I took a break in the middle, and by the time I got back to it I had activated the nVidia glitch and made the game unplayable. (Even with my new graphics card, there are occasional video problems and even crashes, but nothing that couldn’t be overcome by saving regularly.)

Thorgal’s Quest seems to have been a straight-to-bargain-bin release. I picked it up mainly because the packaging was designed to fool you (successfully, in my case!) into thinking it was part of Cryo’s Altantis series. Apparently the original title is Thorgal: La Malediction d’Odin, but the North American release is Curse of Atlantis: Thorgal’s Quest, with “Atlantis” in much larger letters than “Thorgal”. (I’m calling it Thorgal’s Quest here to split the difference.) It just shows how provincial fame is. According to Wikipedia, Thorgal is “one of the most popular French language comics”, and a best-seller as recently as 2006, but over here, it’s so unknown that a tenuous connection to a semi-obscure adventure game series gets top billing.

Thorgal’s Quest seems to have been a straight-to-bargain-bin release. I picked it up mainly because the packaging was designed to fool you (successfully, in my case!) into thinking it was part of Cryo’s Altantis series. Apparently the original title is Thorgal: La Malediction d’Odin, but the North American release is Curse of Atlantis: Thorgal’s Quest, with “Atlantis” in much larger letters than “Thorgal”. (I’m calling it Thorgal’s Quest here to split the difference.) It just shows how provincial fame is. According to Wikipedia, Thorgal is “one of the most popular French language comics”, and a best-seller as recently as 2006, but over here, it’s so unknown that a tenuous connection to a semi-obscure adventure game series gets top billing.

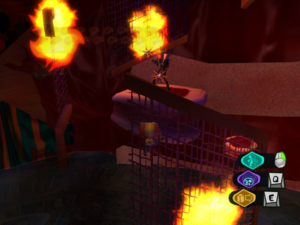

The Atlantis games are first-person adventures based mainly around gratuitous self-contained puzzles slapped arbitrarily on various ancient-civilization backdrops — not the sort of thing I’d easily recommend to others, but sometimes I’m in the mood for it. For example, I was in the mood for it when I bought Thorgal’s Quest, which instead turned out to be a third-person adventure game based mainly around hunting for small objects and occasional archery mini-games.

Thorgal is a Viking warrior who, in the cutscenes, looks kind of like Mick Jagger wearing a tunic and a prominent facial scar. The game starts out with him doing the Odysseus thing, stranded far from home and family by a storm at sea brought on by the wrath of the gods. Enter a magician who shows him a harrowing vision of the future: Thorgal shooting and killing his own son. Thorgal immediately decides that the vision must really be about a shape-shifting villain adopting his guise, and rushes to get home and protect his son before it’s too late, making gamers everywhere shake their heads sadly.

On the way to the lee of the island, where he hopes he can hire a boat despite the storm, Thorgal has an adventure involving some canny bandits who keep the villagers cowed with a fake dragon. Then he almost drowns, only to be whisked away by the same magician to a place called Between Two Worlds, which is your basic Ethereal Void with floating rocks and everything. It was at this point that I really started to suspect that the game was based on a comic book, especially when I met the Guardian of the Keys. Partly it was her apparent role as some kind of cosmic keeper of the balance. Partly it was her appearance: a sexy woman with vivid magenta skin wearing basically nothing but strategically-placed locks of hair. But mainly it was the way that Thorgal already knew her from previous adventures. You could practically see the captions referencing back issue numbers.

Before the Guardian of the Keys can send Thorgal back home, he has to pass a trial involving an interactive representation of his past. And it is here that I learned of his extraterrestrial heritage.

Seriously, now, this has got to seem less bizarre to a player who’s familiar with the source material. It makes me wonder how certain other adaptations I’ve played must seem to outsiders.

It’s also at this point that the Atlantis material creeps in and provides Cryo an excuse to re-use their Altantean skyboat model. Thorgal’s spacefaring parents, it seems, are descendants of people who fled dying Atlantis for the stars centuries ago. Based on what I’ve seen online, I’m not at all convinced that this is canon. It might just be Cryo winking at the fans, much like the Sam and Max cameos in the old Lucasarts games.

It’s also at this point that the Atlantis material creeps in and provides Cryo an excuse to re-use their Altantean skyboat model. Thorgal’s spacefaring parents, it seems, are descendants of people who fled dying Atlantis for the stars centuries ago. Based on what I’ve seen online, I’m not at all convinced that this is canon. It might just be Cryo winking at the fans, much like the Sam and Max cameos in the old Lucasarts games.

I won’t say much more about the story — Thorgal does get home, and the prophecy does come true but not in the manner anticipated, just like you’d expect. All in all, the production is a bit amateurish. There’s some very nice art in the backdrops, but there are also places where the hand-drawn bits are too visible and don’t mesh with the 3-D models well. The story is completely linear, even in some cases blocking actions for no logical reason until you’ve clicked on an NPC often enough to get all his scripted dialogue (even if the last bit is just “Farewell and good luck, Thorgal” or something.) It’s far from the worst adventure game I’ve played, but it’s clearly built for Thorgal fans, who are expected to be a little forgiving.

Comments(0)

Comments(0)