Time Zone: Historical Context

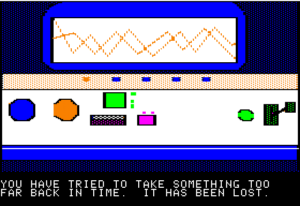

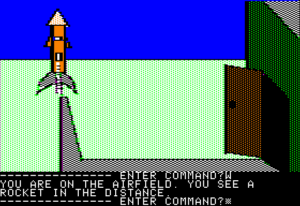

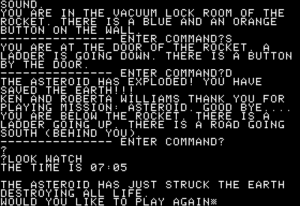

Time Zone was released in 1981 or 1982. (Again I’m finding contradictory claims. The edition I’m playing says “Copyright 1982”.) It was the sixth of Sierra’s “high-res adventures”, and the fourth designed by Roberta Williams. Graphic adventures had been around for about a year, but they were still a novelty, and Sierra didn’t have any real competition. I said before that it uses the same engine as Mission Asteroid, but there was one significant enhancement to it: the use of multiple disks. If I understand correctly, the only previous multi-disk game from Sierra was Ulysses and the Golden Fleece, and the only thing resembling a multi-disk adventure game predating it that I know of is the Eamon adventure/RPG system (which isn’t really the same thing, because instead of being parts of a whole, the disks there were unconnected modules, sharing only the character data on the loader disk.) Sierra was pretty much the first to need multiple disks, because they were filling those disks up with graphics. They’d continue to make multiple-disk games even as disk capacities increased, ultimately turning out several multi-CD FMV behemoths. As far as I can tell, their code for handling resources spread across multiple volumes didn’t change in any fundamental way from King’s Quest 1 onward. But in these earlier days, the Apple II days, things were a little shakier, the seams more obvious. As I mentioned before, different areas in Time Zone recognize different verbs; this seems to correspond to what disk you have currently inserted.

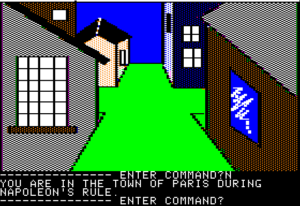

In content, Time Zone reflects a medium in transition. The earliest adventure games, such as Zork and Scott Adams’ Adventureland, were imitations of the original Adventure: treasure hunts set in caves, in an eclectic vague fantasy setting. There’s no story to such a game, there’s just a player’s progress in exploring the cave and collecting the treasures. But after a while, adventure games started mutating into interactive fiction. I think of Steve Meretzky’s Planetfall as something of a watershed in this regard: it was the first adventure game I played that really tried to provide a believable setting and a story that’s revealed by that setting, rather than a premise that’s just an excuse to put the player through a bunch of puzzles, and a backstory which is brought up at the beginning and the end and otherwise ignored. Planetfall was released in 1983, after Time Zone, and while Time Zone isn’t a dungeon crawl, it’s also everything I’ve just said that Planetfall is not. It belongs to a period when the people creating adventures were branching out into other settings, but still treating them like dungeon crawls.

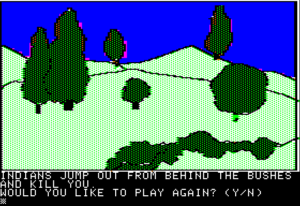

I’ve noted that Time Zone has a repeated puzzle type involving enemies, both human and animal, who will kill you one turn after you enter their rooms unless you first defeat them with some appropriate weapon. This is turning out to be the dominant type of puzzle in the game, not just because it’s used so often, but also because it takes so much longer to solve than other puzzles. It’s basically guesswork, and guessing wrong ends the game, making you restore a save, which involves swapping disks. It’s a terrible piece of design, and it’s repeated over and over. And it may well be the game’s most influential feature. In 1985, an adventure authoring tool called GAGS was created, incorporating foes governed by a slight variation on this mechanic (GAGS monsters don’t necessarily kill you after one turn, but they do prevent you from leaving the room). I may be mistaken when I attribute this to direct influence, but the resemblance is strong. GAGS games tended to use monsters of this sort a lot, because GAGS was a rather primitive system, capable of only a few predefined puzzle types (also including locked doors and darkness). GAGS later became the basis for a more advanced tool called AGT, which was the first really popular adventure engine available to the public. There are scores of freely-available AGT games on the net, many of them entries in an annual competition held on the Compuserve Gamers Forum. And a lot of them contain the monster mechanic that AGT inherited from GAGS, and which GAGS stole from Time Zone.

Comments(0)

Comments(0)