Jolly Rover

Just like last post, we have here a game that I purchased in a bundle deal some time back but didn’t get around to trying until it was made part of the current summer promotion on Steam, and which I finished in less than a day after I finally started it. It probably won’t be the last.

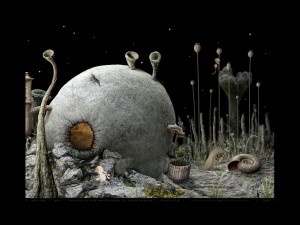

Jolly Rover is one of those games that’s easy to sum up in a single sentence: it’s Monkey Island with anthropomorphic dogs. Seriously, the MI influence here is so strong that I think I have to call it homage in order to avoid calling it rip-off. You’ve got the nerdish hero who becomes a pirate over the course of the game, the damsel in distress who’s more competent than the hero, the voodoo, the ghost pirate, the cannibals who turn out to not really be cannibals, the occasional mentions of circuses, the jungle maze that you can only navigate with cryptic instructions and the cavern maze that you can only navigate with aid from the dead. There’s an opening chapter at a settled island with a pirate bar (where the locals complain about how bad business is lately), which you return to in the end, just before a wedding takes place. It even reuses a couple of MI‘s jokes.

Jolly Rover is one of those games that’s easy to sum up in a single sentence: it’s Monkey Island with anthropomorphic dogs. Seriously, the MI influence here is so strong that I think I have to call it homage in order to avoid calling it rip-off. You’ve got the nerdish hero who becomes a pirate over the course of the game, the damsel in distress who’s more competent than the hero, the voodoo, the ghost pirate, the cannibals who turn out to not really be cannibals, the occasional mentions of circuses, the jungle maze that you can only navigate with cryptic instructions and the cavern maze that you can only navigate with aid from the dead. There’s an opening chapter at a settled island with a pirate bar (where the locals complain about how bad business is lately), which you return to in the end, just before a wedding takes place. It even reuses a couple of MI‘s jokes.

The details are shuffled around, of course. The ghost pirate isn’t your enemy. The wedding doesn’t involve the damsel in distress at all. The circus is part of the player character’s backstory and device for “Son, I’m proud of you” material. The voodoo is primarily a magic system used by the player, with puzzle-solving effects like heating iron and making trees drop their fruit.

The biggest difference is that Jolly Rover is just a much gentler game. I mean that both in the sense that it has a more relaxed ambience, and that it gives the player a lot more help. You get a parrot companion early on who dispenses hints in exchange for crackers (a collectible scattered throughout the game), but outright hints are just the beginning of the help you get. The game highlights clickable objects when you hold down the space bar. It also keeps track of what you’ve done, so you don’t have to: any action with a result you’ve already seen will have its highlight text in white, while any action that yields something new has blue text. This rule holds even when clicking on an item multiple times yields different results: it’ll highlight in blue until it runs out of reactions.

And it’s only polite that it gives you this much help in finding things you haven’t clicked yet, because this is a game that really wants you to click on everything. There are three distinct sets of collectibles — the aforementioned crackers, pieces of eight, and fragments of pirate flags — that can turn up pretty much anywhere. Click a wooden statue, and it might turn out to have crackers stuck in its teeth. Sometimes crackers can be collected from a single barrel multiple times. I haven’t achieved 100% completion in this stuff yet, but this is exactly the kind of thoroughness challenge that obsessed me as a child hunting for all the points in the Sierra games, and so I may come back to Jolly Rover the next time I’m in the mood for mechanically working my way through all the objects in a room until all the text turns white. (It’ll be an opportunity to listen to the Developer Commentary, which unlocks after winning the game once.)

There are two features that I felt worth singling out. First, this is a game with a status line, containing the player’s current score, an old-fashioned rank title determined by that score, and a brief statement of your current Quest: “Join a crew”, for example, or “Find Treasure”, or “Make Salamagundi”. It reminds me a bit of the use of the status line in The Blind House, but here, it’s used for humor: sometimes the Quest line changes several times over the course of a cutscene as the player character’s assessment of the situation changes. For example, at one point it goes from “Make friends with the nice pirate ladies” to “Hide from the scary killer pirate ladies” over the course of an overheard conversation. This particular mechanism obviously isn’t a Monkey Island imitation, but the playful treatment of the user interface struck me as being much more in the spirit of Monkey Island than a lot of the things that imitated it quite closely.

Secondly, there are a couple of items that are too large to carry, but which go into the player’s inventory when clicked anyway, with the explanation that the PC is just remembering where it is so he can move it when he needs it. The inventory item in these cases is just a memory, a token that lets you signify your desire to use a distant object. This is an approach to inventory that I’ve contemplated using before, and not just for exceptional cases, but for everything in the game. Really, all it requires is a slight change of concept: consider inventory not as what you’re carrying on your person, but as the set of tools at your disposal, including anything that you can get at easily. But is such a reconception really even necessary? The way inventory is treated in adventures is typically pretty abstract already. Text adventures sometimes make a nod at realism by putting a limit on how much you can carry and forcing you to drop stuff, but graphic adventures frequently don’t even allow you to drop stuff. We have no problem accepting this, which is a pretty good indication that we’re already thinking of the inventory as composed of puzzle tokens rather than physical objects. Whether this is a good thing probably depends on the story you’re trying to tell.

Comments(0)

Comments(0)