Machinarium: Final Thoughts

I said that I’d finish Machinarium on the PC rather than the iPad, but it turns out I was wrong. I can blame my lengthy bus commute, but that’s only part of it. Despite what I said before, it turns out that the touchscreen version of the interface is easier to use in some situations, particularly when you’re pressing on-screen buttons repeatedly. With a touchscreen, you can hold one finger over each button, essentially treating the screen like a keyboard. With a mouse, and without the hotkeys that usually accompany button-based interfaces in PC apps, you have to keep looking back at the buttons to reposition the cursor over the one you want, and that means briefly looking away from whatever the button affects. This is particularly bad in action sequences.

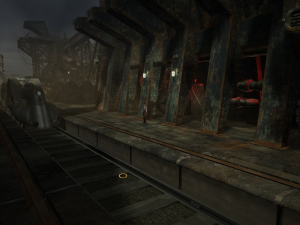

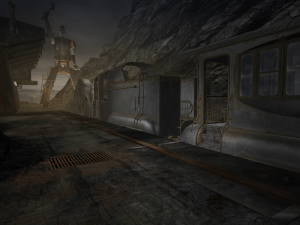

Action sequences? Yes, there are a few, adaptations of old videogames. I’ve already described one: the shooter that grants access to the hints. In addition, there’s a simplified Space Invaders at one point, and, towards the end, a maze-based shooter in a style that reminded me a lot of Atari 2600 Adventure (even if the gameplay was more like Berserk). The context for the Space Invaders is simply an arcade, but the maze game seems to be about cleaning up the software corruption left behind by the bad guys in the mind of the big-headed robot in the city’s central tower.

The bad guys in question are a small band of criminals in black hats who are seen stealing things and even planting a bomb throughout and before the game. Josef recognizes them: they’re responsible, it turns out, for his condition at the beginning of the game, in pieces in a scrapyard, and also show up in a few little flashbacks where Josef remembers when they were mere schoolyard bullies, shaking him down for pocket change and knocking him off the jungle gym, thereby justifying any horrible thing Josef might do to him in return.

Which, of course, provokes the question of whether, and why, robots need to go to school, but the rule of this game is that robots can engage in any sort of human behavior if it’s funny or makes for a decent puzzle. A couple of scenes have toilets in them. An early scene in a jail cell has a cellmate who wants a cigarette, although I suppose that in a sense it makes more sense for robots to smoke than for people to do so. One of the bad guys’ nefarious deeds was to kidnap Josef’s girlfriend and force her to work in the kitchen of a sleazy bar, raising the question of why a robot needs a kitchen, although somehow the “girlfriend” part, with the implication that robots are gendered, doesn’t seem so strange. Well, our concept of gender is at least as much social as biological. Presumably it’s entirely social for robots.

There’s a brief bit where the player even gets to control the girlfriend, which yields one of the game’s better jokes, especially considering that it’s a repeat of a joke you’ve seen over and over by that point. One of the first things we learn about Josef is that his inventory is in his abdomen, and whenever he picks something up or takes it out to use it, he hinges his head open at the mouth like the lid of a trash can. It’s a great sight gag because it combines so many incongruities: he’s turning himself into an inanimate object, but he’s also eating something or vomiting it out, while at the same time being completely unconcerned about what it is or what it’s made of unless its physical properties affect the process of insertion or retrieval (as when he sucks in a length of hose like a child eating spaghetti). Now, one of the things that genders the girlfriend is that her face is more delicate and less machine-like than Josef’s. It would still look monstrous on a human, but relative to the other robots, she’s downright pretty. So when she handles inventory the same way — something she doesn’t even look physically capable of doing — it comes as an extra shock. But it’s also touching in a way, because it also reinforces the sense of a bond between the two of them. They’re two little robot geeks who approach the world the same way.

Also, it helps that there are flashbacks, in the form of line art in thought balloons, showing Josef and girlfriend in happier times. I’ve only seen a couple such — apparently more appear when you stand still in certain locations, which means you’re bound to see one or two over the course of the game, but not more than that unless you’re looking for them. Now that I’m done, I may do that. This strikes me as something that’s missing from most games with kidnapped-girlfriend plots: some indication of what the hero is trying to recover.

Comments(3)

Comments(3)