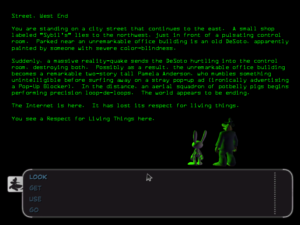

The point I was stuck on turned out to be decidedly lame: the only way to catch the assassin is to actually be attacked by him, and this only happens in one location, at night, if you enter from the right direction. I suppose the designers were thinking that players would naturally walk through that area on the way home from questioning people at the bar, but why walk when you can teleport? This is an example of a problem that plagues Sierra games in general: the problem of plot advancement depending on player actions that the player has no motivation to perform. And in fact it’s a fairly mild example, because once the assassin appeared, it was pretty clear what the trigger was. Mild enough, anyway, for me to get through it.

The point I was stuck on turned out to be decidedly lame: the only way to catch the assassin is to actually be attacked by him, and this only happens in one location, at night, if you enter from the right direction. I suppose the designers were thinking that players would naturally walk through that area on the way home from questioning people at the bar, but why walk when you can teleport? This is an example of a problem that plagues Sierra games in general: the problem of plot advancement depending on player actions that the player has no motivation to perform. And in fact it’s a fairly mild example, because once the assassin appeared, it was pretty clear what the trigger was. Mild enough, anyway, for me to get through it.

Having gotten unstuck, I finished the game with all three base classes. (I haven’t even tried the Paladin yet. I may do so in the future, but even so, the game is now officially off the Stack.) And in all three, I had the full 1000 points. This didn’t work out quite like I expected: unlike earlier games in the series, the maximum score isn’t the total quantity of available points, but rather, the largest score allowed. You can keep racking up more Deeds in the endgame, each accompanied by the score-goes-up noise, but the displayed score never goes above 1000. Once I realized this, in my first endgame experience, I didn’t bother hunting down obscure points with the other characters, and was free to choose whatever wife I felt was appropriate for each of them, regardless of point value.

The first class I finished with was the Wizard. This is because the Wizard is the game’s easiest class. Not the simplest, mind you — that would be the Fighter. The Wizard is much more complex than the fighter. Figuring out the Wizard’s strengths is more difficult, because there are so many more possibilities to try. But once you have a handle on them, you can just exploit them for all they’re worth, and that makes the game easy. Where the Fighter battles his way through Minos’ fortress — a risky, time-consuming process — and the Thief sneaks his way in — also time-consuming and risky, even if the risks are different — the Wizard can pretty much get away with casting Calm and sauntering through. That’s power, man: the ability to walk through a batlefield unmolested. And if you decide you like killing things, like I’ve said, the Wizard is overpowered there too. In the end, you’re joined by several NPCs who fight the dragon alongside you — and, despite my earlier doubts, it is a real battle fought in the game’s regular combat engine — but I can easily see the Wizard trouncing the dragon solo.

But while the Wizard is the easiest, and the quickest to play if you don’t restrain yourself, I think the Thief is the most engaging class this time round. It has a lot to do with the adoption of (simplified) stealth mechanics from other games: QfG5 was released the same year as Thief: The Dark Project and Metal Gear Solid, so it gives you a blackjack and a couple of fortresses full of guards patrolling in regular cycles or conveniently looking in the wrong direction. In previous QfG games, stealth was basically a matter of skill checks to see if people heard you plus a certain amount of special-cased hiding scenarios, not general line-of-sight stuff. Also, you get to sneak around on rooftops. I was always disappointed with the fact that QfG2 — the one in the “Arabian Nights” setting, which suggests Thief of Baghdad hijinks to me — didn’t have any satisfying rooftop escapades, but instead basically just repeated the kind of housebreaking you did in QfG1. So I’m pleased to see some of that here, even if it’s rather small.

But while the Wizard is the easiest, and the quickest to play if you don’t restrain yourself, I think the Thief is the most engaging class this time round. It has a lot to do with the adoption of (simplified) stealth mechanics from other games: QfG5 was released the same year as Thief: The Dark Project and Metal Gear Solid, so it gives you a blackjack and a couple of fortresses full of guards patrolling in regular cycles or conveniently looking in the wrong direction. In previous QfG games, stealth was basically a matter of skill checks to see if people heard you plus a certain amount of special-cased hiding scenarios, not general line-of-sight stuff. Also, you get to sneak around on rooftops. I was always disappointed with the fact that QfG2 — the one in the “Arabian Nights” setting, which suggests Thief of Baghdad hijinks to me — didn’t have any satisfying rooftop escapades, but instead basically just repeated the kind of housebreaking you did in QfG1. So I’m pleased to see some of that here, even if it’s rather small.

My one complaint about the Thief is actually a pretty large one. The Thief can’t always avoid combat. There are several mandatory fights, essentially boss fights that follow a bout of sneaking, and the Thief isn’t very good at them. Traditionally, the Thief’s combat method in the QfG series is to stand at a distance and throw knives, running away if necessary. But I found this unworkable in the new combat UI, so I wound up playing the mandatory combat basically like a less-powerful Fighter. Unfortunately, one of those encounters is with the dragon at the end. I mainly played support on that one in my Thief game, performing functions such as handing out equipment and convincing Gort to sacrifice himself.

I had some trouble at first with the game crashing in or immediately after the final battle — consistently enough that I almost gave up before seeing the congratulations sequence. Either rebooting or playing from a different save helped, I’m not sure which. Anyway, it was anticlimactic. They obviously spent their cutscene budget on FMV scenes of the dragon. After it’s dead, you just have the player and a bunch of NPCs gathered in the throne room talking. You get to choose whether you want to actually be king or not , and your engagement (if any) is announced, and that’s it, unless you’re playing a Thief, in which case you can get an additional scene in the Thieves’ Guild where you’re proclaimed Chief Thief. If you choose to become king, you don’t even get a crown, or at least not where the player can see it. I want my crown! Sir Graham got a crown when he became king of Daventry. He had to pick it off his predecessor’s corpse himself, but it was a crown.

I had some trouble at first with the game crashing in or immediately after the final battle — consistently enough that I almost gave up before seeing the congratulations sequence. Either rebooting or playing from a different save helped, I’m not sure which. Anyway, it was anticlimactic. They obviously spent their cutscene budget on FMV scenes of the dragon. After it’s dead, you just have the player and a bunch of NPCs gathered in the throne room talking. You get to choose whether you want to actually be king or not , and your engagement (if any) is announced, and that’s it, unless you’re playing a Thief, in which case you can get an additional scene in the Thieves’ Guild where you’re proclaimed Chief Thief. If you choose to become king, you don’t even get a crown, or at least not where the player can see it. I want my crown! Sir Graham got a crown when he became king of Daventry. He had to pick it off his predecessor’s corpse himself, but it was a crown.

But then, all of the endings in the series were disappointments compared to the impact of the ending scene of the original QfG1: the celebration, the reiteration of prophetic verses that you understand now (with no mundane dialogue to spoil it; we’re in storytelling mode now), then the music transitions to the gentle Erana’s Peace theme while the credits roll over the hero and his new friends floating lazily on a magic carpet over the valley where the game took place — your first view of the valley as a whole! This is what you were saving, kids! And finally, the barest hint of what was to come in the forthcoming sequel. If there’s one element of this that I think would improve the ending to QfG5, it’s the shifting away from NPC dialogue to narrator voice. That’s what we really need at the end of an epic: something along the lines of “And so King Baf ruled wisely, and lived to an old age” or whatever.

I’ve spent a lot of time on this game now. Probably more than it deserves. I don’t try for perfect scores on every game I play, let alone perfect scores with every character class. I’m quite happy with my “43% complete” in GTA3. But I have some sentimental attachment to the QfG series. And as such, I don’t even feel qualified to say if anyone who doesn’t have my attachment to it should play it at all. It has its ups and downs (and silly clowns). I’ve been complaining about the bugs and gameplay issues a lot, but if nothing else, it has some really good music, always one of the high points of the series.

Next post: Something new.

Comments(1)

Comments(1)