Time Zone

Mission Asteroid was just an appetizer. Now for the main course. Time Zone, which uses the same engine as Mission Asteroid, originally shipped on twelve Apple II floppies (or possibly six double-sided floppies; my information is a little iffy here), making it easily the largest microcomputer game ever released at the time. I vaguely remember that Roberta Williams said it would take well over a year for anyone to complete it, and was disappointed when someone managed it within a week of its release. But this story may be apocryphal, or might be true of a different game entirely.

Mission Asteroid was just an appetizer. Now for the main course. Time Zone, which uses the same engine as Mission Asteroid, originally shipped on twelve Apple II floppies (or possibly six double-sided floppies; my information is a little iffy here), making it easily the largest microcomputer game ever released at the time. I vaguely remember that Roberta Williams said it would take well over a year for anyone to complete it, and was disappointed when someone managed it within a week of its release. But this story may be apocryphal, or might be true of a different game entirely.

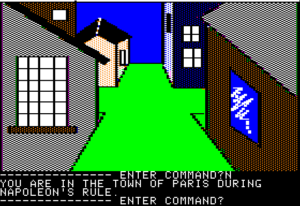

It’s a time-travel game featuring eight areas (seven continents plus one alien planet) in eight time periods, which makes for 64 possible combinations (65 if you include the “Home” setting), although apparently only 39 of them are actually visitable. I haven’t gotten very far in it yet. I’m still in the wandering-around phase, and will remain wandering around for some time. There are a great many filler rooms: mazes of featureless streets, King’s Quest-like grids of empty wilderness. This was released at a time when the size of an adventure game was often measured in rooms, an idea famously discredited by Level 9’s Snowball, with its thousands of useless algoritmically-generated locations. At least Time Zone gives each filler room a unique illustration, which accounts for most of the disk usage.

Comments(3)

Comments(3)

So is Roberta Williams’ work brilliant or distinctive in some way? I guess I consider the Infocom-era writers fairly inspired, to have created artifacts of lasting merit. But I’ve never played RW’s work – I know she’s famous but I don’t know if her oeuvre has held up the same way.

Well, I don’t want to understate the importance of her works. Ken and Roberta Williams (it’s hard to say who is more responsible for the design decisions here) invented the graphic adventure. In fact, they invented it twice: first as illustrated text adventure, then, with King’s Quest, as adventure with integrated, interactive graphics. Ms. Williams was an innovator, and much of the success of her games comes from the fact that she was the first to see how new technology could be used in the adventure game medium. Another example: the use of scanned paintings as backgrounds in King’s Quest V. It had never been done before. The effect stunned people at the time.

But she was never a skilled writer, and at the point when she wrote the games I’m playing now had not yet become a good game designer (if she ever did, which is debatable; I myself enjoyed her later works, but wouldn’t recommend them to others without reservation). I’ve made the comparison before to the early days of color cinema, when moviegoers had a choice between “story or color”. Since color films were novel, they didn’t have to be good, and since black-and-white films were competing with color films, they had to be better than they used to.

[…] anyway. For those that do, alteration of history is prevented by what Carl Muckenhoupt (whose own posts on Time Zone I highly recommend as companions to this one) calls “the poverty of the game engine.” […]